The government, with the cooperation and collaboration of the media, used propaganda to justify the use of atomic bombs against Japan.

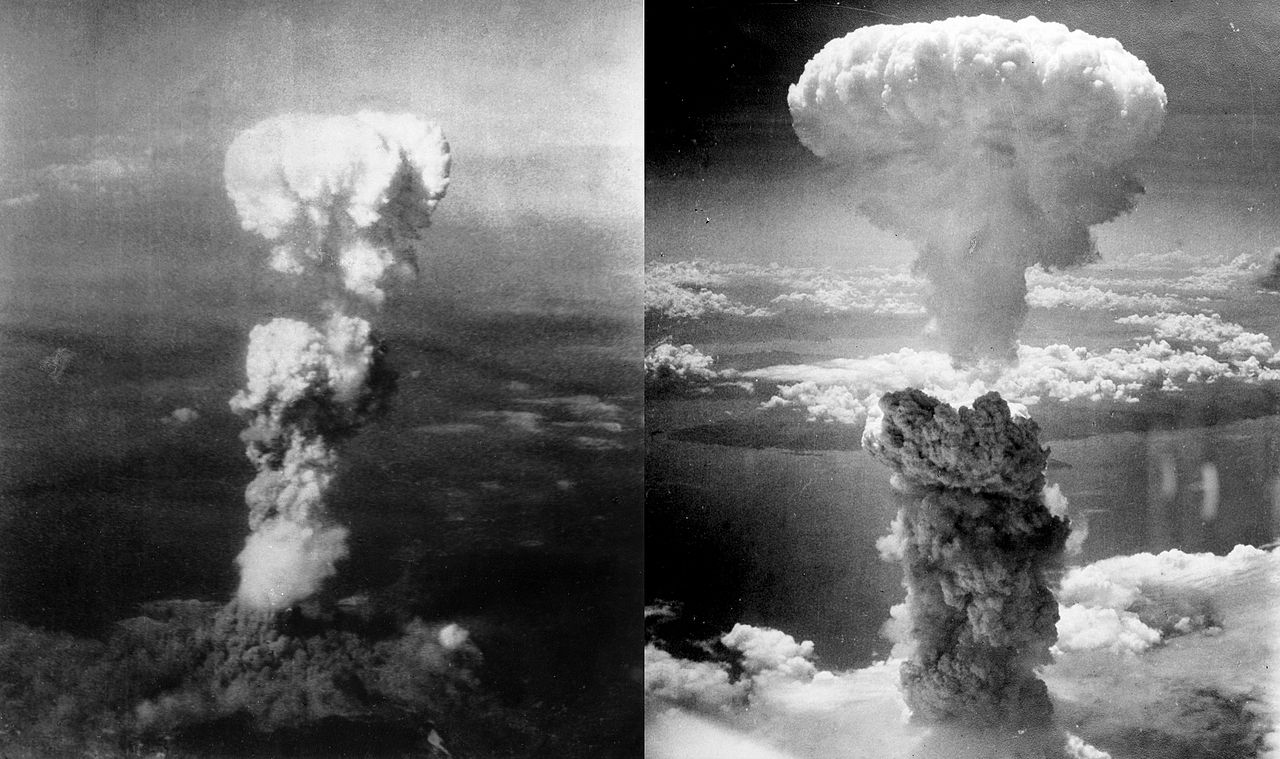

The dropping of an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, August 6, 1945, and, at right, the bombing of Nagasaki three days later. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

I was only nine months old when two atomic bombs killed about 210,000 men, women, and children — the first at Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, and the second at Nagasaki on August 9.

I have had discussions with soldiers and sailors who were fighting for the U.S. in the Pacific Theater during World War II. All of them held the view promoted by the government and most media in 1945 and thereafter that using atomic bombs was necessary to prevent the loss of 46,000 American lives (a worse case estimate made by military authorities) if the U.S. invaded Japan to end the war. This was and has been over the years the view of most Americans.

We know now that the official

narrative is false.

We know now, however, that this narrative is false. Records released by the government over the past three decades reveal facts that belie the official version of events leading up to these bombings: the only times atomic bombs have ever been used against human beings.

The late Howard Zinn explained most of this in his pamphlet, Hiroshima — Breaking the Silence, published 20 years ago. (All quotes in this essay are from that pamphlet.) But many people have never learned anything beyond the propaganda widely disseminated by the government and the media during and after the war in the Pacific.

Zinn wrote,

When private bands of fanatics commit atrocities we call them “terrorists,” which they are, and have no trouble dismissing their reasons. But when governments do the same, and on a much larger scale, the word “terrorism” is not used, and we consider it a sign of our democracy that the acts become subject to debate.

However, the most widely accepted description of terrorism is “the indiscriminate use of violence against human beings for some political purpose.” This is a fair and accurate description of the use of the atomic bombs known as Little Boy and Fat Man detonated over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively.

The government wanted to keep the Soviet Union out of the Pacific Theater.

It was claimed that the U.S. wanted to convince the Japanese to surrender (in spite of their known willingness to do so) and we know now that the government wanted to keep the Soviet Union out of the Pacific Theater to diminish its influence and demonstrate the superior weaponry of the U.S.

To understand how we got to that point in 1945, Zinn believed that we had to look at the indiscriminate civilian bombing that had occurred both in the European and Pacific theaters of war. Using the work of sociologist Kai Erikson, Zinn asked what would cause a society — what moral arrangements — would lead a decent people to perpetrate or acquiesce to or accept the burning of children in such large numbers or the deaths of thousands more due to radiation poisoning, stillbirths, birth defects, and infant mortality.

The question is even more urgent today because we have bombs with tens of thousands of times more destructive power than the two used in Japan in 1945. And we spend billions of dollars each year to procure other deadly so-called conventional weapons while millions of people die each year because of inadequate food and medical care.

Zinn explains the background of WorldWar II by noting the moral righteousness of the fight against Fascism:

But it is precisely that situation — where the enemy is undebatably evil — that produces a righteousness dangerous not only to the enemy, but to ourselves, to countless innocent bystanders, and to future generations.

The government’s objectives may be different from those of the people.

That the enemy was unquestionably evil, Zinn argues, does not mean that we were unquestionably good. The use of the pronoun “we” is the first problem Zinn notes because it wraps the people’s motives up with the government’s motives when the two are not necessarily one and the same. The government establishes the moral issues as one and the same as that of the people to persuade them to support the government’s efforts, but the government’s objectives may be different from those of the people.

An example of this disparity occurred over 100 years ago when “we” ousted Spain from Cuba ostensibly to liberate Cubans, when the government’s purpose actually was “to open Cuba to our banks, railroads, fruit corporations, and army.”

In World War II, the U.S. fought against fascism to be sure — international aggression — while failing to acknowledge the international aggression previously carried out by the U.S., England, and France with their “long history of imperial domination in Asia, in Africa, the Middle East, (and) Latin America.”

The self-determination that our government claimed to support at the end of World War II did not end the colonization of Indochina by the French, of Indonesia by the Dutch, of Malaysia by the British, of the Philippines by the U.S.

In the 1950s, the U.S. gave extraordinary aid to the French who were trying to maintain their dominance over the people of Indochina and secure for themselves and the U.S. tin, rubber, and oil needed by our industries. The Defense Department’s own official history of the Vietnam War revealed that in 1942 President Roosevelt gave assurances to the French that our government agreed that French sovereignty would be reestablished over its colonial conquest as soon as possible.

The U.S. refused to help Jews over and over again as the Nazi war machine churned.

While the plight of Jews under the Nazis’ racist policies has stirred the hearts of several American generations, fewer Americans seem aware that this country refused to help Jews over and over again as the Nazi war machine churned, demonstrating that the lives of Jews were not the highest governmental purpose in fighting Hitler (and Mussolini). And there were other demonstrations of America’s own racism, namely the internment of Japanese-Americans from the western U.S. without cause and without due process.

But indiscriminate bombing of civilians during World War II was official policy of the Allies, as well as Hitler. The relentless Allied bombing of Dresden was experienced as a child by my late friend Margret Hofmann, who served on the Austin City Council in the 1970s. She carried those terrifying memories to the grave. My former in-laws, along with most British children living in cities, were removed to the countryside for protection from German bombing.

Civilians were targeted in Cologne, Essen, Frankfurt, and Hamburg (which was bombed so intensely that it created a firestorm with hurricane-like winds). At the time, the chief of the British Air Staff estimated that this policy would destroy 6 million homes and kill 900,000 people, obviously an acceptable outcome to the Allies.

When it came to the Japanese, Churchill said ‘We shall wipe them out, every one of them…’

American fighter planes machine-gunned German refugees clustered on the banks of the Elbe River on February 14, 1945. When it came to the Japanese, Churchill said “We shall wipe them out, every one of them, men, women, and children. There shall not be a Japanese left on the face of the earth.” The British did area bombing runs at night with no pretense that they were aiming only at military targets. High altitude bombing by the Allies was never accurate, even if military targets were being aimed at.

As many as 100,000 Japanese civilians in Tokyo were killed by night bombing at low altitudes with napalm and magnesium incendiaries on March 10, 1945. The atmosphere reached temperatures of 1800 degrees. Those who jumped into the water to escape the flames were boiled alive as reported by Japanese journalist Masuo Kato. Weeks later, there were similar raids on Kobe, Nagoya, Osaka, and another on Tokyo in May.

The U.S. media contributed to the dehumanization of the Japanese by publishing pictures, such as that in Life Magazine, of a Japanese civilian burning, captioning the picture with “This is the only way.” The attitude of U. S. Air Force General Curtis LeMay was summed up by his statement, “There is no such thing as an innocent civilian.”

The American people had been conditioned to accept almost any atrocity.

By the time the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the American people had been conditioned by the war propaganda to accept almost any atrocity. In June of 1945, American troops experienced “the bloodiest battle of the Pacific War” on the island of Okinawa. Just after this loss by the Japanese, its Supreme War Council authorized its Foreign Minister to contact the Soviet Union, America’s ally at the time, “with a view to terminating the war if possible by September.”

On July 13, Japanese Ambassador Sato wired Foreign Minister Togo that the Emperor of Japan wanted a swift termination of the war. The U.S. government knew about this message because it had broken the Japanese code earlier in the war. The only dispute was whether Japan could keep its Emperor, an idea that was rejected by the U.S. at that time, but accepted later after the atomic bombs were dropped. This circumstance has led many commentators and historians to conclude that the U.S. was eager to show the world (and especially the Soviet Union) its latest armament and be in the position to dictate the terms of the war’s end.

The secret diaries kept by President Truman, released in 1978, support this view. The bombs were dropped just days before the Soviets were planning to enter the Pacific Theater against Japan, portending a final death knell for the Japanese. But the U.S. rushed to use their new weapon before the Soviets could claim any credit for ending the Pacific war.

Truman had learned of the Japanese peace initiatives at least three months

before the bombings.

From 800 pages of secret documents released in 1994, the historian and economist Gar Alperowitz reported that President Truman had learned of the Japanese peace initiatives at least three months before Hiroshima and Nagasaki were bombed. A German diplomat notified Berlin in May 1945 that large sections of the Japanese armed forces were willing to capitulate. This information was passed up the U.S. chain of command by U..S intelligence analysts.

A U.S. invasion of Japan was never going to be necessary, so there was no need to drop the atomic bombs to preserve American lives in an invasion. America’s most revered general, Dwight Eisenhower, explained his feelings about the proposed atomic bombing when the plan was revealed to him by Secretary of War Henry Stimson, who headed up the “Interim Committee” assigned the task of deciding on the targets for the bombing:

During the recitation of the relevant facts, I had been very conscious of feelings of depression and so I voiced to him (Stimson) my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives.

In a similar vein, Admiral William D. Leahy, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, explained his views:

The use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender.

While President Truman announced that the bomb was dropped on a military base, the facts reveal that Truman was dissembling. While there were 43,000 Japanese military personnel in Hiroshima, there were 250,000 civilians. The bomb killed all who were in what Zinn called “its circle of death,” both military and civilian.

The government knew that there were American prisoners of war in the kill zone.

Nagasaki was bombed even though the government knew that there were American prisoners of war in the kill zone, just one mile from the center of the city. Later, war documents revealed that American prisoners also were killed in the bombing of Hiroshima. Some who survived were described by a Japanese physician as having no faces — missing eyes, noses, mouths, and ears, which were burned or melted away by the blast.

It is irrational to blame Japanese civilians for the attack on Pearl Harbor (a frequent justification given for the use of the atomic bombs) any more than it is to blame German refugees slaughtered in Dresden for the holocaust. All Americans cannot be blamed for the horrors committed against the Vietnamese, just as all Muslims cannot be blamed for the terrorism of a few who subscribe to that religion.

When we join together to create a government, we cannot know how badly that government might behave in the future. Certainly, America’s founders did not envision a government that would send its military around the world to force its will on a substantial portion of that world. But before we can do anything about the inexcusable behavior of our government, we must recognize war propaganda for what it is — information or ideas methodically and deliberately spread to promote the desire for war or the acquiescence in war.

The government, with the cooperation and collaboration of the media, used propaganda to justify the use of atomic bombs 70 years ago. We can work against such manipulation by educating ourselves, by speaking out, by standing against the manipulation, by demanding honesty from our elected and appointed officials, and by openly and directly challenging their deceit.

History suggests that we have not been very successful in this endeavor to date. Maybe the future will be different, but there is little about the world today that convinces me this will be so.

Read more articles by Lamar W. Hankins on The Rag Blog.

[Rag Blog columnist Lamar W. Hankins, a former San Marcos, Texas, City Attorney, also blogs at Texas Freethought Journal. This article © Texas Freethought Journal, Lamar W. Hankins.]

Its about time the truth got out. Dropping two atomic bombs on Japan was undoubtedly the worst atrocity in history.