Socialists versus the Klan in South Texas.

The political atmosphere in Texas after World War I was markedly different. The several years of patriotic fervor that had stemmed from U. S. involvement in the European war had created a very uncomfortable climate for those who had chosen to oppose the American intervention.

Before the World War, the Socialist Party of Texas had grown to a political force which had elected dozens of local office holders in the state as it championed the cause of tenant farmers and industrial workers, but its opposition to the War had resulted in its leaders being jailed, its newspapers being shut down, and its members subject to physical and political attacks.

Thomas A. Hickey, the Texas socialist firebrand who himself had been detained without a warrant in the early months of the War and who had seen his newspaper, The Rebel, the first in the nation to be shut down by the federal Espionage Act in 1917, was determined to revitalize the Socialist movement in Texas, but his efforts to reestablish a couple of new newspapers simply fizzled. The Socialist Party of Texas itself had almost evaporated; its state secretary had been among the arrested, its state chair had resigned, many of its speakers and organizers were imprisoned, and, faced with ongoing government pressure, the bulk of the membership had simply faded away. At its convention in Dallas in October 1919, the Socialist Party of Texas declared itself officially dead.

The political mood in Texas had definitely continued its pendulum swing towards the right.

The political mood in Texas had definitely continued its pendulum swing towards the right. Political repression and an anti-union climate, clothed in the vestments of patriotism, continued against socialists, labor organizations such as the Industrial Workers of the World, and the Non-Partisan League. On the national level, the U. S. Attorney General’s office under A. Mitchell Palmer began a policy of police raids and deportations against suspected foreign radicals. In 1919, the American Legion was organized by a group of 20 Army officers under the leadership of Theodore Roosevelt Jr. with a stated goal of opposition to socialists, the I. W. W., and conscientious objectors.

The years after the World War also saw a dramatic increase in the membership of the second coming of the Ku Klux Klan. Formed in Atlanta in 1915, the resurgent organization developed a warped sense of righteousness and Americanism which involved a hatred of African-Americans, Mexican-Americans, Jews, Catholics, immigrants, bootleggers, socialists, and all others falling short of the Klan’s parameters of morality. Its marketing-based membership program attracted white middle-class businessmen. It had reached into Texas by 1920; by 1924 it had elected a U. S. Senator, controlled the Texas Legislature, and elected a large number of judges and court officials, as one of its stated goals was to control the judiciary. Klan growth in Texas was marked by an increasing reign of terror; one report in the files of the U. S. Bureau of Investigation cites dozens of instances of Klan violence over a three-month period in 1921.

With other socialists Hickey established the National Workers Drilling and Production Company.

After an unprofitable stint as an organizer for the Non-Partisan League, Tom Hickey found himself cast in the role of an oil operator when the black gold boom was launched in Desdemona, in Eastland County. Hickey knew Desdemona and its socialist citizenry well; he had been a yearly speaker at the socialist encampments in nearby Ellison Springs. With other socialists Hickey established the National Workers Drilling and Production Company.

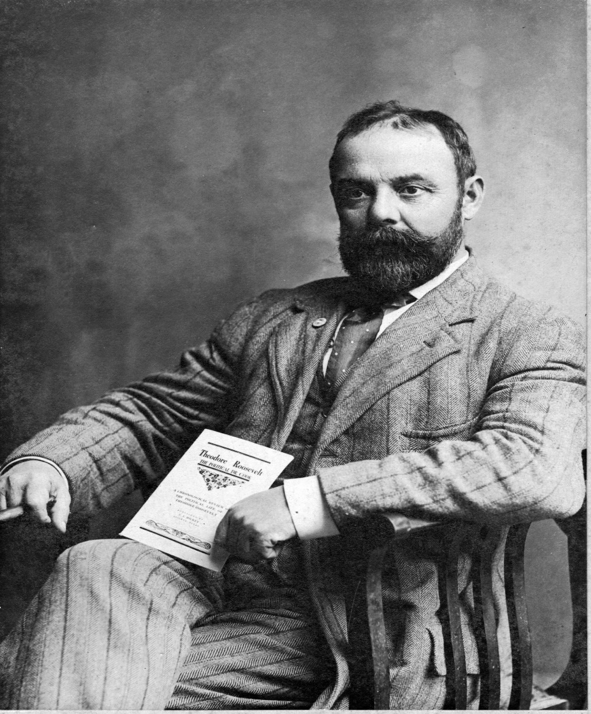

The new company was primarily established to manage the oil leases on the properties of the numerous socialist farmers in the area and had been roughly set up as a collective ownership corporation; shares of stock in the company were sold to the public. One of the many stockholders was Jay R. Secrest, who had been Tom Hickey’s secretary and stenographer since at least April of 1916.

Jay Secrest was born on May 2, 1892, at Koerth in Lavaca County, Texas, the son of Thomas Allen Secrest and Mary Jane Hogan. He attended public schools in Halletsville and business college in Yoakum, where he studied law and trained in stenography. His father had established a Socialist Party local organization in Koerth in 1915, but J. R. Secrest was a socialist in his own right, becoming one of the primary directors of the Socialist Printing Company, publishers of The Rebel.

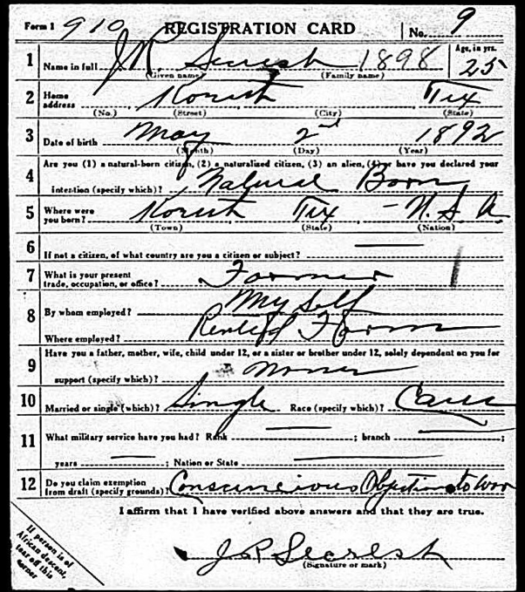

Secrest registered for the military service draft and noted that he had a ‘conscientious objection to war.’

Secrest registered for the military service draft on June 5, 1917, as required by law, and noted in his enrollment that he had a “conscientious objection to war.” He served with apparent distinction in the Argonne Forest as a corporal in Company A of the 128th Infantry Regiment in the 32nd Infantry Division, returning to the United States on May 5, 1919.

Jay R. Secrest’s draft registration card with with his conscientious objection noted. From Ancestry.com.

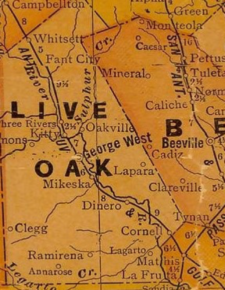

Later that year Secrest’s entire family moved to Simmons City in Live Oak County, where patent medicine manufacturer Dr. C. F. Simmons had broken up his 60,000-acre ranch into parcels for sale to small farmers. J. R. became a real estate broker in the partitioning and sale of the Simmons tracts of the new town and was later hired as the teacher and principal at the newly formed Simmons City school.

Secrest followed in the footsteps of his mentor Tom Hickey and became the associate editor at the George West Enterprise, and he was also elected as the commander of his American Legion post at George West. In this connection, it is remarkable that he authored an anti-Ku Klux Klan resolution for his post which was unanimously passed by the membership, even while other American Legion posts in the state and around the country were disrupting socialist meetings and meeting halls.

Tom Hickey visited Secrest at Simmons City in July of 1921.” In a letter to his wife Clara Boeer Hickey, he talked about how that voting box in Live Oak County was “one of the most Socialistic boxes in the United States,” that it had cast 41 votes for Socialist Party Presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs in the 1920 Presidential election as opposed to 15 votes for Republican Warren G. Harding and 12 votes for Democrat James M. Cox. Hickey was staying at the hotel of “comrade” Hugh Davis House, a former Socialist Party candidate for county attorney in Fisher County.

Hickey also noted in his letter to Clara that he and Secrest were “out to secure members,” presumably for the Non-Partisan League, adding that the “comrades” there had secured many abandoned land tracts from the breakup of the Simmons Ranch which might prove to be attractive to other “comrades.” Given Hickey’s previous track record as an advocate for tenant farmers, he may have been involved with Secrest in an attempt to provide affordable land to disenfranchised farmers; toward that endeavor, former Socialist Party activist and co-publisher of The Rebel Ernest R. Meitzen, then an organizer for the Non-Partisan League, had visited Simmons City in an organizing spin that January.

The influx of new people to Live Oak County and the new city of Simmons, especially those of a political persuasion which may have been deemed by some as not patriotic enough, may have raised the dander of the old-timers in the county. Hickey had written to his wife that the county was divided into two camps, “old settlers who want no improvements v the progressives who want schools road and bridges.” Jay Secrest also commented on this political climate when he wrote to Hickey that a mutual acquaintance nicknamed “the fortune teller” had received a “bogus K.K.K. notice recently and has wanded her way to the Alamo City. The rest of the citizenry is up in arms and there is very little talking, gosiping [sic] and meddling just at present.”

By the middle of 1922, the political tension in the

county had intensified.

By the middle of 1922, the political tension in the county had intensified. Secrest reported to Hickey that at the first of the year [1923] the Klan would “take charge of everything:”

Bro. Buck and I fought the KuKoo Krowd to a finish but they swamped us at the polls. Do you think that an Anti-sheet could be made to pay if it was run on a large scale? I want to get into something there is some fight to — damn this dignified school room stuff.

One of the candidates “swamped at the polls” in Live Oak County was County Attorney Emmet W. Smith, a political ally of Secrest and Hickey.

Secrest also remarks that H. D. House had defeated “our friend” John H. Casey, the long-time County Commissioner from Whitsett in Precinct One of Live Oak County, possibly indicating an ideological shift on the part of House. Secrest was contemplating leaving the county: “Do you blame me for wanting to skidoo?”

In a November letter to Hickey Secrest repeated his desire to leave Live Oak. “[I] want to get away just as soon as I can connect up with something that there is a living in.”

Simmons City today. Photo by the author.

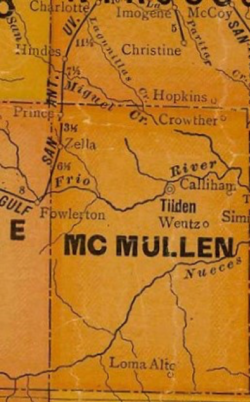

In 1923 Jay Secrest was able to leave Simmons City and Live Oak County, but he did not go far. Petroleum production was beginning in earnest in the small hamlet of Guffeyola by the Calliham Ranch, about 18 miles west of Three Rivers, just inside the McMullen County line. Oil developer William M. Stephenson worked with ranch patriarch Joseph Thomas Calliham to establish a town site at the small settlement and the new town was renamed Calliham. In July, Secrest published the first four page issue of the Calliham Caller and Three Rivers Oil News and was working to make it the anti-Klan “sheet” he had discussed with Hickey the previous year.

Things had changed for Hickey as well. His editorial employment at the Kosse Cyclone had not panned out, and his job at the National Oil Journal fizzled out as well when that paper went belly up. Jay Secrest invited him to help on the Calliham Caller, an offer which Hickey accepted, arriving in early December.

Hickey the socialist had become Hickey

the capitalist entrepreneur.

In a short time Hickey became secretary of the McMullen County Chamber of Commerce and was actively selling oil leases and real estate with Secrest. Even while he remained a stalwart progressive, Hickey the socialist had become Hickey the capitalist entrepreneur. Perhaps realizing that he was not getting any younger and that his health was not getting any better, Tom Hickey probably decided he wanted to finally settle down with Clara; his letters certainly try to convince her to move to Calliham.

Jay Secrest announced for the Texas Legislature from House District 76 in January 1924, filing for the seat vacated by Frank H. Burmeister, who had filed for the State Senate. Tom Hickey also displayed political ambitions, filing for County Commissioner. Both races added fuel to an already heated election season which would prove to be one of the deadliest in Texas history.

Hickey did not waste any time at the Calliham Caller in continuing the feud with the Klan. His February 8, 1924 column in the paper recounted the recent history of a criminal libel lawsuit filed by then Live Oak County Attorney Emmett W. Smith against Klan preacher and well-known evangelist Walter James Bugg of the Hyde Park Baptist Church in Austin, who had addressed a Klan revival at George West. That case in November 1922 had so inflamed tensions in Live Oak County between the Klan and anti-Klan factions that the Texas Rangers had to be called out to maintain order.

His February 15, 1924 column was more aggressive:

In the name of peace they rend communities asunder and put neighbors at each others throats, and break all family ties and this is done, all of this is made possible simply and solely because the founders of the modern klan have made their millions by dragging the word hate from the jungle…. Klanishness and hate are synonymous terms and in that one word we find the origin of the KLAN.

Hickey heightened his attacks in a February 29 column which revisited the Rev. Bugg. The account implied that the Reverend had purportedly been involved in a Klan-style sado-masochistic whipping with a confessed sexual deviant in a Philadelphia hotel room. Hickey’s account appears to be an error or a fabrication, as the person involved in that whipping was not named Bugg and the alleged whipping had happened in 1917, but it led Hickey to conclude that “I will not for a moment claim that every K. K. K. is a sexual degenerate…I will dare any K.K.K. to deny that every sexual degenerate in the United States is a K. K. K.”

Another Hickey column on March 28

continued the attacks on the Klan.

Another Hickey column on March 28 continuedthe attacks on the Klan, calling them “ignorant,” “intolerant,” “bigoted,” and “self-righteous.”

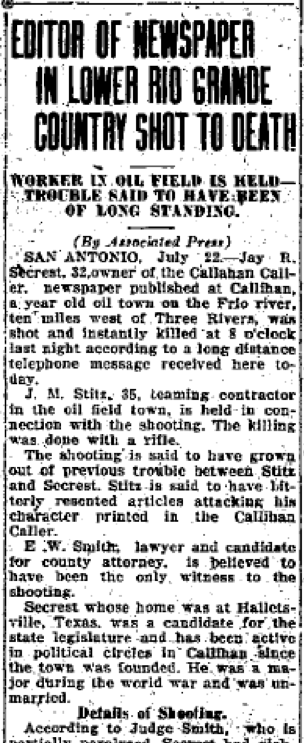

The feud was quickly boiling to a head. In early July, Jay Secrest was arrested and jailed by McMullen County Deputy Sheriff James Valentine Stitz for allegedly making statements against the Klan in the Caller. “Secrest had aroused the ire of Kluxers by his pronounced anti-Klan views,” reported the United Press. Hickey passed the information along to his wife: “There has been a very bitter Ku Klux fight here. Jay was framed up and arrested as you read in the Caller.”

Deputy Stitz was born July 14, 1893 at Runge, in Karnes County. His father, John Stitz, moved his five children to McMullen County in 1911 after the death of his wife and purchased 880 acres adjacent to the property of Joseph Thomas Calliham. John Stitz’s eldest child, Lillie May, would marry Joseph Calliham’s son, Joseph Edward Calliham. John Stitz and his oldest son James V. Stitz leased numerous oil plots to developer William M. Stephenson in the years prior to 1924, would develop at least eight productive oil wells, and their estate would be involved in legal litigation with Stephenson until as recently as 2017.

Some newspaper accounts of the time reported that the differences between Secrest and Stitz had been of “long standing;” the two men may have had conflicts over the legislative race, there may have been competition over the sale of oil leases, and there may also have been personal animosities. But the charges on which Jim Stitz arrested Secrest apparently had no compelling grounds, even while there were apparently good enough reasons resulting in the circumstances of the arrest for Sheriff William S. Goff of McMullen County to dismiss Stitz from his post. Following Secrest’s release, Stitz “was relieved of his badge and his gun.”

Stitz was most probably a member of the Ku Klux Klan.

Stitz was most probably a member of the Ku Klux Klan; he is identified as such by Tom Hickey’s biographer, Peter Buckingham. While the Klan did not appear to have had organized “klaverns” in Live Oak or McMullen counties, they did have an active membership there and had established groups in the nearby communities of Alice, Bee County, Mathis, Bishop, and Kingsville. Membership rosters of the “Invisible Empire” are not usually accessible; the Klan’s shrouded white hoods demonstrate their desire for secrecy. In reference to Stitz, the Calliham Caller would assert that the Klan had rejected him. Stitz was more than likely operating at the behest of others in his capacity of deputy or was seeking to gain recognition from or membership in the Klan.

In any event, Stitz would continue the next phase of the feud by filing a lawsuit against Secrest for “interference with an officer.”

The July 18, 1924 issue of the Calliham Caller would unleash on Stitz even while mentioning his name only once:

Mr. J. W. Wright has been appointed deputy sheriff to take the place of Jim Stitz. The Caller editor happened to be the first person upon whom it was Mr. Wright’s duty to serve papers. [These legal papers would presumably have been the Stitz lawsuit.]

Secrest and Hickey had apparently been digging up as much dirt as possible on Stitz:

A lady [has] a board bill that this alleged officer refused to pay. The bill was made last January and has only been due four or five months. We wonder if the lady won’t be charged with “undue respect to an officer.”

Please don’t ask us why we do not mention his name. We do not want to make a smudge in the columns of our paper by printing the name of a man who was once charged with incest — a crime against his own sister.

We have said many hard things about the ku klux klan as an organization…. As we have said before it is the organization that we have fought, but it could be worse. The commonest piece of humanity we ever knew lives at Calliham and the ku klux would not have him.

The incest charge might have been why Stitz was not accepted for formal membership into the moralistic Klan.

While Stitz’s name was not mentioned specifically in regards to the Caller’s incest accusation, it would have been known gossip in the community to whom the newspaper was referring. The reference to “once charged” indicated that the accusation was not a recent matter; but there does not appear to be any available documentation of any such charge against Stitz in the court records of McMullen County. On the other hand, the incest charge or rumors thereof might have been the reason that Stitz was not accepted for formal membership into the moralistic Klan.

At about seven in the evening of July 21, five days before the Democratic Party primary, Jay Secrest was returning from the oil fields accompanying former county attorney Emmett Smith to Smith’s hotel in Calliham. They were confronted by Jim Stitz, who had been following them. Stitz blocked the passage of Secrest’s roadster with his own vehicle and at the point of a rifle demanded an editorial retraction from Jay Secrest. When Secrest refused, Stitz, without a further word, shot the unarmed Secrest twice on the street in Calliham.

One shot pierced Secrest’s jugular vein; the second round hit Secrest in the heart. He was killed almost instantly. The partially paralyzed Emmett Smith, who was running for Justice of the Peace in McMullen County, was the sole witness to the shooting. Stitz drove on to the county seat of Tilden and calmly turned himself in to Sheriff Goff.

Hickey reported to Clara from Jourdanton, where had finished getting out what was presumably the last edition of the Calliham Caller. “Jay was shot and killed and died in my arms last Monday at 7 pm. I cannot tell you how it shocked me.”

In the same letter to Clara he “expect[s] the paper to live and I will be in charge;” but Tom Hickey never returned to Calliham. He dropped a brief line to Clara on August 3 from an express office in San Antonio: “The killing of Jay in cold blood has demoralized me temporarily. There is no hope for Calliham now….The town is hopelessly split into KKK and Anti-camps.…The Caller is suspended and I believe forever….Human life is still very cheap in Texas.” He continued on to Fort Worth, where he again wrote Clara in early August.

It may be that Hickey fled Calliham in fear for his life.

It may very well be that Hickey fled Calliham in fear for his life. “I am about recovered from the terrible shock of Jay’s death: you will never know how near I came to being buried in the same grave with Jay…The leaders of the klan are murderers at heart….,” he wrote Clara on August 22.

Jay R. Secrest was buried on July 25 in Lavaca County, about 13 miles south of his home town of Hallettsville. It does not appear that Tom Hickey attended his friend’s funeral, as he was in Jourdanton at the time and was not listed among the attendees.

Hickey may have been feeling a sense of guilt over his friend’s death. The paragraphs with no byline in that fateful issue of the Caller bore a striking similarity to Hickey’s writing style, and Secrest was referred to in the third person. The attacks on Stitz were sharp while Secrest’s signed adjoining column was more moderating. It is quite possible that Hickey was the author of the incest charge against Stitz, continuing the Hickey motif of Klan “degeneracy”, whereupon Hickey’s apprehension of being “in the same grave” as Secrest would have been a valid concern.

It would not have been the first time that Hickey’s journalism would have caused havoc.

It would not have been the first time that Hickey’s journalism would have caused havoc. An investigative article in 1914 about probable financial mismanagement among the City Hall gang in Hallettsville would result in the shooting of former Lavaca County Judge Edward Otto Meitzen, publisher of The Rebel and father of Non-Partisan League organizer E. R. Meitzen, when the elder Meitzen pursued the investigation. Meitzen would survive the attack by City Marshall O. T. East.

Hickey again expressed his angst to Clara on September 3: “…physically at least I am over the shock of my poor pal’s death altho I can never never never forget it. The anguish of soul and spirit when he died in my arms is unforgettable. Nobody can ever tell how much damage the infamous klan has caused.” From Fort Worth he published the first issue of Tom Hickey’s Magazine on October 1, returning to his progressive politics and again rallying for Texas tenant farmers, but nothing was mentioned about Jay Secrest or the Klan.

Jim Stitz did not remain in Calliham either. He apparently was not jailed following the murder, as he appeared in Uvalde in November as the informant on the death certificate of his stillborn son.

If there was any redeeming quality to Jay Secrest’s murder, it might have been that the election of 1924 marked the beginning of the end of the Klan in Texas. Miriam A. “Ma” Ferguson handily defeated Klan-backed candidate Felix E. Robertson in the Democratic primary for Governor with one of the heaviest votes in one of the bloodiest election cycles in Texas history. In addition to the Secrest murder, anti-Klan sheriff’s candidate Mel J. Dwight had been assassinated in his own garage in Childress County, and Klan attorney Levi Old was shot and killed in Uvalde. Hickey reported to Clara that former governor James E. “Jim” Ferguson had escaped an assassination attempt.

Ironically, E. W. Smith was appointed as Justice of the Peace in Calliham in early 1925, replacing Jim Stitz’s brother-in-law Joseph Edward Calliham. Ma Ferguson beat Robertson by a two-to-one margin in McMullen County, but unexplainably no second primary election was held in Live Oak County. The Klan had been predicted by political analysts to predominate in Live Oak, continuing its hold on the county from the 1922 election cycle.

On January 12, 1925, a McMullen County grand jury indicted Stitz for murder, charging that Stitz “did then and there unlawfully and with malice aforethought kill Jay R. Secrest by shooting him with a gun.” Following the indictment, a warrant was issued for Stitz’s arrest and he was apprehended on the 13th. Stitz made an application for a writ of Habeas Corpus on the same day and bail was set at $10,000, which was met by his father, John Stitz, and one A. E. Pursch.

The case was set for trial on January 19. District Attorney Sid D. Malone began issuing subpoenas for witnesses for the State; interestingly, one of the first witnesses subpoenaed was Mrs. Lillie May Calliham, Jim Stitz’s sister. As Mrs. Calliham does not thereafter appear in any of the court proceedings, presumably her questioning by the District Attorney was relative to the incest charge.

Neither Tom Hickey nor E. W. Smith could be located and subpoenaed as witnesses in San Antonio, where they were determined to have gone. E.W. Smith was eventually served with process at his home town of Chireno, in Nacogdoches County in east Texas, where apparently he too had fled following the shooting, leaving behind a law practice in Simmons City.

It soon became apparent that an impartial jury could not be had in McMullen County.

It soon became apparent that an impartial jury could not be had in McMullen County:

…[T]hat a trial of this action alike fair and impartial to the State and to the defendant cannot be had in this McMullen County, Texas, because of the condition hereinabove set out, as well as because of the general notoriety given this action, as well as because of the interest and friendship of the prospective jurors in this county for the parties involved in the transaction out of which this prosecution arose….

On January 21, 36th District Judge Thomas M. Cox ordered a change of venue to neighboring Live Oak County, with a new trial date set for January 26.

With all the Klan influence in the Texas judiciary and in Live Oak County during those early years of the Roaring Twenties, some speculation occurred as to whether Judge Cox himself was a member of the Klan. During the 1922 elections, Cox was asked point-blank by his opponent, L.D. Stroud of Beeville, if he were a Klan member. Cox declined to answer.

Some speculation occurred as to whether Judge Cox himself was a member of the Klan.

While Cox’s Klan membership was undetermined, the Klan membership of his predecessor on the bench was known. Judge Cox was named by Governor Pat Neff in August 1922 to fill the vacancy of M. A Childers, who was entering private practice. Childers became Grand Dragon of the Texas Klan in October 1924. Childers was also one of the trustees of oil speculator W. M. Stephenson’s Grubstake Investment Association, and was specifically named as a defendant in the lawsuits by the Stitz family.

After a series of continuances and delays, Stitz’s trial finally convened at the Live Oak county courthouse in George West on June 13, 1925. James V. Stitz pleaded not guilty. He was represented by four attorneys, including powerhouse attorney James R. Dougherty of Beeville and State Representative Frank Burmeister of Christine in neighboring Atascosa County. Dougherty had represented the Stitz family on a number of other matters, had invested deeply in the Calliham oil fields, and was an active member of the Catholic Church. Interestingly, Dougherty was also a high ranking member of the Knights of Columbus, an organization which found itself at great odds with the Klan.

Dougherty and his associates argued that the “defamatory statement” in the July 18, 1924 issue of the Caller “appears from the uncontssradicted testimony that such statement was untrue.” The lawyers then presented an argument of self-defense to the court and jury, arguing that Stitz had the right to demand a retraction from Secrest and had the right to arm himself, because “there was a reasonable probability of some character of attack upon him by deceased…that might be anticipated.”

Then Judge Cox added his own eyebrow-raising last charge to the jury.

The trial lasted three days. Judge Cox read the standard statutory charges of the court to the jury which explained the various legal standards for homicide—malice aforethought, self-defense, manslaughter, and the “adequate cause” for murder. Then Judge Cox added his own eyebrow-raising last charge to the jury:

Insulting words or conduct of the person killed towards a female relation of the party guilty of the homicide are deemed adequate causes.

And in this connection you are charged that the article published in the Calliham Caller charging the defendant with incest with his sister is, under the law, deemed adequate cause.

On June 16, jury foreman I. B. Rice delivered the verdict: “We the Jury find the defendant Not Guilty.”

Jim Stitz would not stay in Calliham. By 1927 he had abandoned his wife, Georgia Elia Canion Stitz, and his two daughters, and left Texas. He appeared in the 1930 Wyoming census and had remarried, quite possibly bigamously. According to local history, he was declared dead by his relatives, yet he reappeared in McMullen County in 1937 at the settling of his father’s estate.

Calliham would see continued oil production for the next several decades, but the original town, as well as the location of the original Stitz wells, would disappear under the waters of the Choke Canyon Reservoir in June 1982. The current town population of about 165 is located about three miles south of the old Calliham town site.

Jay Secrest is interred in the Salem Cemetery near Ezzell, in Lavaca County.

For documentation on this article find footnotes at this link.

[Steve Rossignol is a retired member of IBEW Local 520 in Austin, Texas, and a member of the Blanco County Historical Commission. He is an frequent contributor to The Rag Blog.]