Battle of Algiers:

White vigilantes and the police in Katrina’s aftermath

By scott crow / The Rag Blog / September 8, 2010

“…within the war we are all waging with the forces of death, subtle and otherwise, conscious or not – I am not only a casualty, I am also a warrior.” –Audre Lorde

On the fifth anniversary of Katrina I want to share this narrative about anarchist organizing in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. This piece is made of stories about the early violence we came across in dealing with the white vigilantes and police in Algiers. It takes place upon my return to the area after a failed mission to find my friend Robert King of the Angola 3 right after the levees failed.

It also contains characters who had done something good only to reveal themselves as less than honorable, and somewhat harmful later. These stories take place just prior to organizing the http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Common_Ground_Collective Common Ground Collective. This is a rough draft excerpt from my forthcoming book: Black Flags and Windmills: Hope, Anarchy and the Common Ground Collective.

Five years later we have only scratched the surface of the atrocities of the vigilantes and the police. Many of us are still healing from those encounters. This story is just one of them.

On September 4th I was back home in Austin, resting uneasily from my draining trip. I received a call from my friend Malik Rahim who unknown to me had also remained in New Orleans. He on the other end of the crackling phone line saying we got racist white vigilantes driving around in pick up trucks terrorizing black people on the street. It’s very serious. We need some supplies and support…

He and his neighbors were being harassed and threatened by armed white men and the police. He had been interviewed for a piece that appeared in the San Francisco Bay View in California that explained the grim situation in detail. I had read it upon my brief return back to Austin. Now he was on the phone because he had heard I was just in NOLA looking for [former Black Panther and Angola 3 defendant] Robert King. I knew he was serious. He said he hoped I would come back to New Orleans to give them support and use it as another opportunity to search again for our friend King who was still missing.

Malik Rahim is a serious man with a broad smile and a big laugh. He was a former Black Panther, the Defense Minister for the New Orleans chapter. His days have been given to making the world a better place since that time. Throughout much of their lives, the histories of the men of the Angola 3 have been intertwined with that of Malik. He and King had not only been Panthers together, they had also been childhood friends in the Algiers neighborhood. I had visited him at his mom’s house a few times with King at the beginning of the century.

After living in Oakland, California for years, Malik had settled once again in Algiers, where through King he and I had become friends in 2001. It’s one of the oldest neighborhoods in New Orleans, situated across the Mississippi from the French Quarter.

Malik, too, had waited out the storm at his home with a woman named Sharon Johnson. While Katrina left massive damage in her wake it hadn’t flooded his neighborhood. Malik had no electricity and no water, but his phone still worked, and when he called I knew it was critical that we move quickly. No electricity, but a live phone. It reminded me of the days just earlier in the leaky vacant warehouse. What an odd coincidence I thought as we spoke.

With determination I decided I was going to go back there to deliver supplies and get to King. This was a chance to try again to find out what had really happened to my friend. The only thing I knew was that he had been trapped in his house, surrounded by dirty water for eight or nine days. I hoped he was still alive. Robert King had been in solitary confinement for 29 years in a 6’ x 9’ cell. I could not let him sit in the floodwaters any longer; I felt a duty to try and get to him.

On the way out of Austin again I stopped at a meeting called by local anarchists and activists who were organizing local aid for evacuees. I shared my stories, tears, fears, and the scary realities of what was happening on the ground. I then asked if anyone in the circled crowd of 50-60 people would come to New Orleans knowing what might transpire. Sadly, there weren’t any takers. Was I doing the right thing?

After my first trip to the Gulf I knew better what to bring on this mission: water, food, candles, matches, ammunition and guns; nothing more and nothing less. We were not prepared enough the first time — we were outgunned and under resourced — but not this time.

Fear of the unknown crawled under the surface of my skin, fear of what was about to happen as I headed back. I knew it was getting more desperate in the Gulf as time passed. Was a race war going to erupt? How many people had died needlessly already?

I had seen from the first trip the disregard and lack of empathy that some white rescuers had shown to desperate people. It had made me deeply angry but I had generally kept my mouth closed. I was torn between doing the work of simply helping people, and espousing my political ideals in the face of oppressive ignorance.

We hurried back to the scene of the floods, our truck speeding alone on the highway headed into an abyss. Few cars moved our way, apart from the occasional military vehicle. In the other direction the roadway was overflowing with evacuees — who began to look like refugees from another place.

People were piled into and on top of vehicles, carrying with them the remnants of their lives; others, stranded without cars, traveled on foot. Families, neighbors, and strangers trying to go somewhere — anywhere — that was away from the flooded areas. All the while the government repeated on the radio “order will be restored” when all anyone wanted to hear was that they would do what ever it took to get everyone to safety. It was a modern day exodus, caused by corruption and unresponsiveness that didn’t have to happen.

I asked myself “what the hell am I getting into?”

We changed course to go along the lower southwestern coastal route this time, traveling into what looked more and more like occupied war territory with military vehicles and personnel at every turn. I wondered if the doctored passes that we made would get us past the bureaucracy we knew was already rearing its head.

The military and the state only understood badges and uniforms. They wouldn’t let civilians help even though it was the right thing to do. Many of the young soldiers looked war-stressed and distant as we came up. They grilled us about why and where we were going. Half truths got us through; it was the only way.

After the last checkpoint we drove headlong onto the empty bridgeway; I knew we were “safe.” I let out a sigh of relief and continued to Malik’s. Ours was the only truck on the road, so we ignored the dead useless stop lights.

So much water so close to home

Algiers is situated in New Orleans, on the south and west sides of the Mississippi river in an area called, ironically, enough the “West Bank.” Like the West Bank halfway around the world in the Middle East, it too had an apartheid system — with two unequal populations. Before the storm, the West Bank was home to 70,000 people. It had a largely poor black population, and a small, wealthy white minority. Governments rendered the larger populace invisible in daily life; why would a storm make it any different?

Huge housing projects and surrounding neighborhoods were burned out or empty, first from neglect, and now the storm. There had been no social services or safety nets to speak of for decades. When the last clinic closed 10 years earlier it stayed that way, and it was the same with many shuttered schools.

It was surrounded by massive graying concrete levees on the Mississippi sides — almost like prison walls — which didn’t give way, despite nearly being crushed by a huge barge ship that Katrina had run aground within a few feet of the levee walls. This was why it hadn’t flooded, even though the river had swollen to the top of the levees.

After the storm, most residents were gone, with only about 3-4,000 remaining behind. Many were people who couldn’t leave. They had no money, transportation, or family support, or were elderly and in ill health. The storm had made an already terrible situation much worse for them.

The police command structures in the fourth district of Algiers were in shambles. There was scant military help on the ground on this side of the river. The city center — the money-making sections — were the most important to those in power. They had to get NOLA open for business and they neglected everything else.

There were dead bodies on the ground, and buildings smoldered in flames from unknown fires. Algiers, like the rest of New Orleans, was only a remnant of its former self. It was isolated geographically and psychologically from the other side of the river and the outside world.

What was called law enforcement at this stage was erratic, disorganized, and reactionary. It was made up of city, county, state, and some federal officers, but mostly it was Louisiana-based. If they had a plan — besides acting like thugs with badges — it hadn’t been revealed.

As in life before Katrina, laws were subjectively enforced. There were different standards for whites and everyone else, and threats from officers were all over the map in severity. They were accountable to no one but themselves. There were heavily fortified military zones and check points around the area but nothing inside. The residents were left to fend for themselves against the police.

Trapped in this situation, cut off from the rest of New Orleans and the world, Malik Rahim, Sharon Johnson, and a few nearby neighbors struggled to provide basic aid to each other with rudimentary food delivery of military MRE’s (Meals Ready to Eat) and water provided by a distant government military.

They had few resources: one busted-ass car with limited gas, including what they could find from abandoned cars. There was no Red Cross, no FEMA — nothing. To get anything you had to have a vehicle, and access to gas and money to buy it. Someone had to drive 20-30 miles to a remote military outpost, wait in a long line under armed security — and hope they would be let back into their community before curfew without running out of gas or being shot. The ordeal would take the whole day. That was all they had — there were no other options.

Tapestries of violence

This community had asked for support, so I returned to do what I could. It was what many of us on the outside with conscience would be doing in the weeks to come. But today that was an eternity from where I stood.

I arrived in New Orleans for the second time seven days after the levee failure on September 5th. Everyone pitched in to unload the supplies we had brought. Then the conversation turned to discussing the best way to search for King.

Before we did anything else, Malik took Brandon and me down the street to cover up the dead bullet-riddled body that lay near his house with a piece of sheet metal tin. The bloated and putrid body had been left there for days. We could smell it as we approached. Malik hoped someone would come and get it soon. But who was looking for this man, unknown to any of us, including the kids who found him?

His image haunts me among the string of deaths I experienced during my time there. He met an ignoble death without a chance. Left to decay on the sun-baked street, where others I had seen had been in the waters. I imagined they all deserved better. His death was a product of his skin color, economics, and chance.

We started establishing safety and security for ourselves and our immediate neighbors. Something else had happened in the short interim since our first arrival in New Orleans. While the state was in crisis, white vigilante militias had formed in Algiers Point and in the French Quarter district. These white vigilantes were little more than an organized mob. Signs on the backs of their trucks announced that it was their job to secure law and order in the absence of the police. The militia in Algiers seemed to be made up of drunken racist fools.

Algiers Point is a small, very wealthy, very white neighborhood that is about 10 blocks long in each direction. It is very separated from the Algiers neighborhood. Both sections are part of the broader Westbank, which is predominantly black working class, and poor.

Algiers Point was the only neighborhood on the West Bank where when traveling down the mostly abandoned and littered streets we saw hateful signs like “You loot, we’ll shoot” or “Your life ain’t worth what’s inside.” Signs proudly displayed on the houses that were still occupied, as well as the ones that were vacant and boarded up.

These kinds of signs were put up by the vigilante types who stayed. They believed it was their right to protect their private property and secure law and order. It was as if the dam of civil society that kept them from acting out their most racist tendencies had broken enough to allow their ugly hatred to emerge. They had another shot at the good old Klan days and they were going to take it.

This armed white militia rode around through largely low-income black communities and meted out their version of justice — intimidation — around Algiers and the West Bank. Their “defense,” as they called it, amounted to harassment of any unarmed black person on the street alone. With pride they acted and talked tough, never offering to help anyone who wasn’t white.

Their incendiary vigilante actions, thinly veiled under the guise of protecting themselves and their private property, was gasoline on the fire of the undeclared war on all who were desperate. I found myself asking what kind of people are more interested in their private property and security than in the well-being of another human?

I could understand the concept, given the right situation, of an armed group of people gathering to defend themselves in the absence of the state, and this disaster could be seen as such a situation. But ultimately in their racist actions and words they acted no better than Klansmen straight out of the old Deep South, as they paraded around in their trucks. Our conflicting ideas of what community self defense meant were on a collision course.

In those early days, the Algiers Point Militia openly threatened — and may have killed — desperate unarmed civilians. They foolishly bragged about it to a Danish media crew and to anyone else who would listen. Local representatives of the state, or what little remained of it, with their ingrained racist attitudes towards these marginalized communities they were supposed to protect, stood by and let these vigilantes do their thing.

There were bullet-riddled bodies of black men in the street, including one that we tried to get picked up for 15 days while it decomposed. Was it the vigilantes or was it the police or both? Those men’s bodies were on different streets — found separately — near nothing of value. Who killed these men? I know now — as I believed then — that the vigilantes or the police had killed them and gotten away with it.

In this country, on city streets, they killed people and were accountable to no one.

They regularly both drew their guns on, and shot at, numerous innocent people who happened to be unarmed, poor, black, and on foot, to scare and intimidate them. They threatened Malik—who they mockingly called the “Mayor of Algiers” — from the beginning, pointing guns as they would drive by, threatening to “get ’em.”

The police did nothing but close their eyes and continue their own harassment and shooting campaigns. The lines between law and thugs blurred, leaving people with nowhere to turn.

Undercurrents

From the moment I had set foot into the Algiers neighborhood and spoken with Malik and Sharon Johnson in more detail, I realized that this was going to be bigger, more difficult, and more dangerous than anyone thought. They were both exhausted from having to struggle for survival and remain vigilant about the militia and the police. There had been no help. People were left on their own.

Although Algiers had not flooded, it had been ravaged by the storm, and the long term neglect before that. The water was still high along the levees down the block rising at the edge of the dead end streets to the north and east sides of the banks; spirits were low in the streets below, but some desperate hope remained among those residents who had stayed. This had always been their home and they didn’t want to leave.

I had been here a few years before with Malik and King, who showed me their old stomping grounds as kids and young hustlers, before they became Black Panthers. Now, like the rest of city, trash and abandoned cars littered the empty streets and vacant lots. I asked myself — as I came in and passed the armed, sandbagged turrets at the intersections — what damage was new and what had been that way for a long time?

This place had been occupied by a police force before, but now the outskirts were occupied by an army that watched from bunkers without helping the people within. Military vehicles patrolled many of the city streets. It looked like low intensity warfare against a civilian population, not aid, eerily reminding me of what I had seen in Belfast and in East Berlin.

Immediately after delivering water and food, we met and talked with residents from the neighborhood who were scared and fed up with the white militia and the police. People, mostly men with little or no resources, both young and old, told us the stories of their live, and why they had stayed.

Some were forgotten vets from U.S. government wars, others had seen prison time for essentially being Black in Louisiana, while some were quiet and deeply religious men. But they all stayed because they had to. All of them had long family histories within these city blocks; many houses were multi-generational.

They cared about where they stayed and what happened to their neighbors. They worked together to make the most of a bad situation with no resources. They were men and women who had been reduced to statistics by the media, the government, and civil society; they were virtually invisible, characterized only as poor, black, unemployed — branded as hoodlums, drug addicts, or any other number of de-humanizing words — and now they were being called looters for managing to survive.

The small group talked about what we might do to defend ourselves should it become necessary. There were conflicting opinions on how the police might react, but we felt we had no other choice today. We inventoried what we had among us. Who was in, and who could have nothing to do with carrying arms.

Eventually — with Brandon Darby, Reggie B. and “Clarence” (not his real name) carrying civilian AK-47’s and a .45 caliber pistol, and me with a 9mm carbine rifle — we began our first rudimentary watches, standing or sitting on Malik’s porch and waiting, armed.

I wasn’t a white man taking it on himself to protect helpless locals. There was no machismo. I was anxious and honored to be amongst these people. To me this was solidarity with people whose lives were being threatened simply because of the color of their skin.

Being there was an expression of my anti-racist principles, my personal relationships, and my revolutionary beliefs that already existed before the storm. I had been asked for support and came, not blindly but as a matter of principle. I had come back ready to defend friends and strangers in the neighborhood, because they asked me to. They wouldn’t have, had it not been necessary. Civil society had given them no choices. It looked as if they were left to die. We had to at least give ourselves a fighting chance for survival.

I was a community organizer from another city who believed that the right to self-determination and self-defense are fundamental if we are going to have just communities. I accept the fact that dismantling coercive systems that hold people down will require various tools, and sometimes it might involve defending ourselves and our communities. Even if a violent world in the future is what we want to avoid. It is one of the hard and dirty realities that we must sometimes face while moving towards liberation.

Comrades in the Crescent City by the river asked — and I said yes. I was terrified but resolved in what I was doing. I had little previous experience in community self-defense. I had been tested on a much smaller scale — resisting neo-nazis and small time fascists, confronting police brutality in the streets, facing threats from private security for my environmental or animal rights work. But this was on a scale unlike anything I knew.

I had had a few years of firearms practice, but now I needed to transform a conceptual framework of armed self-defense into a reality with many unknowns. It was all to happen so quickly too, without much or time for processing or reflection. It was now time for action.

Friends of Durruti

The midday humidity hung heavy and the helicopters continued their constant noise in the overhead sky. A few neighbors remained gathered at Malik’s, a long narrow “shotgun” style house built in the thirties that sits high off the ground with a tall concrete porch behind a rusting chain link fence.

The white vigilantes came around the corner in their truck — and as before — slowed in front of the house on Atlantic Avenue, talking their racist trash and making threats. But this time it was different — when they came we were there, and nervously holding our ground — armed. There were four or five of us — most from the neighborhood — and we held the high ground.

We had more firepower, a better firing position and we were sober. Finally someone said for them to move on down the road. They would not be able to intimidate or threaten any more residents around here. In a flash this could turn bad in a hail of bullets. Time was standing still, each moment passing slowly, with my finger on the trigger of my rifle.

Earlier, we had all informally agreed that some of us would hold the space no matter what, although it wasn’t clear exactly what that meant. The previous days had been harrowing, but this was one of the most unnerving situations of my life.

After a few words were exchanged, the truck drove on without further incident. My heart and my head pounded with sickness and relief. I was shaking inside from fear and adrenaline. The incident seemed to have lasted forever, but in reality it probably happened over a few scant minutes. In opposing them we had made our presence known.

My head swirled with a tidal wave, with more questions than answers. How was the state going to react? How were we going to react? Was this the right thing to do? What if the situation continued to escalate? Would other movement groups support us? What if I had shot someone — or worse killed them? Would it have been worth it?

Some of these men in the truck were known to Malik and his neighbors. Had the veil of society stopped them from this kind of aggression in the past, and now they felt free to kill as they pleased? Even if they were ignorant they had no real power once they were challenged; this was immediately apparent. As they left there we felt guarded joy and relief — they were gone but would they stop their attacks on the neighborhoods?

More volunteers would sit on Malik’s porch over the days to come and begin rudimentary neighborhood patrols, to keep the militia threat, and to a lesser degree the police, at bay. These acts and our refusal to leave in the face of repression made us enemies in the eyes of law enforcement, and race traitors to the racist militias.

I came to help, not end up on a porch with guns facing down a truck full of armed men. I, like the others, was ready to die defending the community from attacks. It meant something to them — especially at that time — that white people would come to their aid and put their lives on the line with them — as more would do as the days progressed. It had a profound effect on me, that by circumstances and choices we

had taken the step to not lie down, but to rebel against giving up hope.

There was no Red Cross, there was no FEMA, there was no protection except what we all were willing to organize ourselves. Under siege we stayed and soon myths were born from words that would take on lives of their own, as many currents swirled and converged taking us in new directions.

Sometime later the presence of whites and blacks working together in solidarity defense of these communities against the racist militia would be cited by local residents as one of the acts that helped ease the tensions in a racially and economically divided area devastated before the levees ever broke.

From self defense we created the Common Ground Collective based on anarchist principles and practice. An organization always at odds with the state, that took direct action to meet the needs of communities left to die.

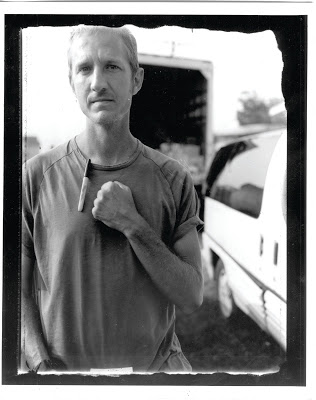

[scott crow is an anarchist community organizer and writer based in Austin, Texas. He was one of the founders of Common Ground Collective, an organization formed in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 to aid in the rebuilding of New Orleans.]