It is precisely because Eastwood has made the sexual angle central to the film, without playing games with it, that the film is so powerful.

By David McReynolds / The Rag Blog / November 17, 2011

[This is the first of two Rag Blog reviews of Clint Eastwood’s new film, J. Edgar. Also see “Eastwood’s Biopic of Kinky Hoover” by Jonah Raskin.]

J. Edgar Hoover (1895-1972) who, depending on your politics, looked much like a toad… or a bulldog… was without question a monster of American political life. Since his life is now so distant to those younger than 40, the film, J. Edgar, has great value as an historical “look back” at the life and career of a deeply flawed, remarkably powerful man.

As a fan of the work of Clint Eastwood I wish I could give the film unqualified praise, but my praise, while real enough, is limited by two regrets.

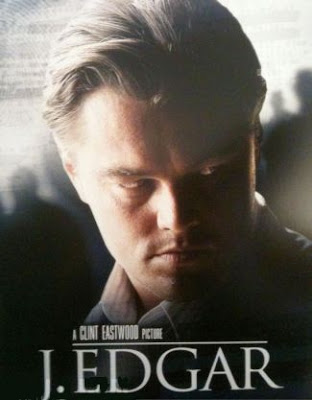

First — while I’d credit the actors with filling their roles so that we soon enough forget Leonardo DiCaprio was so recently the golden boy of youth, as he ages toward the stout, balding figure of Hoover, and that it takes some time to realize Hoover’s mother is played by that most accomplished of actors, Judi Dench — makeup and acting cannot always accomplish miracles.

In the case of Armie Hammer, who plays Clyde Tolson (Hammer played the double role of the Winklevoss twins in The Social Network), his acting skills do not make him believable as an elderly Tolson, crippled by a stroke. Sadly, the makeup leaves him looking as if he were headed for a Halloween party.

Second, I quarrel with Clint Eastwood’s approach in which past and present shift throughout the film. But that was his decision and the film works despite my quibble.

There are some things which might have been covered in the film. Younger viewers will not know that Hoover persisted in denying the existence of the Mafia — so much so that it became a kind of joke (to which passing reference is made in one of the Hercule Poirot TV mysteries). There were suggestions that the Mafia might have had something on Hoover. It is just as likely that Hoover felt the Mafia too big a challenge.

Hoover’s role began in 1924, when he was appointed the first director of the Bureau of Investigation, which later became the FBI. His role was to combat “subversion.” In the wake of the Russian Revolution, and the folly of some acts of violence by American radicals (to which I’ll return later), there was widespread fear of a “Bolshevik Revolution.” Hoover played a key role in the Palmer Raids, the deportation of hundreds of aliens.

Then, in the early 1930’s, in part linked to the conditions of the Depression, criminal gangs held up a number of banks in the Midwest and John Dillinger became a kind of national folk hero. The FBI played a key role in jailing the gangsters.

On the eve of the Second World War, the FBI investigated German agents and had the key role in counterespionage. With the rise of the Cold War, Hoover became obsessed with the danger of Soviet spies and “un-American” groups. There are few of us who were politically active in that time who do not have FBI files.

(Mine was about 300 pages, when I got it under the Freedom of Information Act, and it was for the most part accurate — though I was amused that the FBI agent assigned to my case wrote that I was a Trotskyist, basing his conclusion on his access to the documents of the Communist Party’s “Control Commission” in Southern California!)

Pacifists often met with FBI agents in the course of routine checks being made on men who had applied for status as conscientious objectors. I met with agents on several occasions when they were asking if certain men were, in fact, members of the War Resisters League. (I always said yes, whether I knew them or not, as it might help get them a CO status and keep them out of jail.)

I remember one such meeting in the early Sixties when I was serving a 25-day jail term on Hart’s Island for taking part in a Civil Defense protest. I was on a work crew, dirty from digging. I smoked then, and was very short of cigarettes. A guard came down to the work crew and called me out, saying the FBI wanted to see me.

Grimy and in need of a smoke (which the agent generously offered), I was asked some routine questions about someone applying for CO status. When I got back to the work crew my prestige had, I soon found out, risen greatly, as the men assumed I was involved in some major crime to merit an FBI visit.

A month or two after I finished that short term, I was in my office at 5 Beekman Street when the same agent came in with similar questions — and, in clean clothes, I was happy to offer him a cigarette.

There are other areas the film might have covered. (I’m not faulting Eastwood for choosing to focus on the personal life of Hoover — only noting areas younger people wouldn’t be aware of.) During the Vietnam War Hoover chose to ignore the Supreme Court limits on his power and set up a “dirty tricks” program called COINTELPRO which sought to disrupt the Black Panthers, Martin Luther King Jr., SCLC, the Communist Party — and the War Resisters League.

While we at WRL were never able to prove it, it was our assumption that the raid on our offices in 1968, when the office machinery was wrecked, the office badly messed up, and the membership files stolen, was a COINTELPRO project.

This only touches on the dirty world of J. Edgar Hoover, a man so powerful, with his vast secret files, that no president dared to fire him. A man who could destroy careers, drive people of talent, but of left-wing views, to seek new lives in Europe. (One interesting act of defiance — remarkable at the time — was the detective story The Doorbell Rang by Rex Stout, author of the Nero Wolfe series. Written in 1965, when Hoover was in full power and no one could safely criticize him, Stout ends the story with Hoover ringing the bell on Wolfe’s West 35th St. home — and Wolfe left it unanswered).

However, J. Edgar does what perhaps most needed doing — humanizing Hoover as a sad, sexually frustrated, deeply insecure man who tried to rearrange facts to help insure his place in history. A man whom Presidents feared, never liked, and never dared to fire.

There had been rumors for years that Hoover was homosexual. His relationship with Clyde Tolson certainly provided the needed grist for the mill.

Hoover had been at his job for several years before he was introduced to Clyde Tolson. There are surely few of us who have not had that electric moment when we met a person to whom we were instantly drawn. In most cases those electric moments never light a real fire, but when Tolson turns up in Hoover’s office, having applied for a job, there is absolute clarity about the relationship. Tolson “takes charge of the scene,” moving to open an office window, handing Hoover a handkerchief to mop his face, which had broken into a sweat.

Tolson is hired. Hoover soon makes him his second in command — a post Tolson accepts “only if you will agree we will always have lunch and dinner together.” It is clear that Tolson is in love with Hoover, and quite aware of that. It isn’t clear whether Hoover is ever able to really come to terms with the fact he has a lover.

It is, I think, quite possible the two men never had an actual sexual encounter. But in a remarkable scene, which homosexuals will recognize as valid, when Hoover tells Tolson he is thinking of marriage there is a sharp sudden physical encounter, breaking glass, and the two fight, hitting each other, tumbling and wrestling together until Tolson, on top, says “I love you” and kisses Hoover.

Hoover says “Never do that again,” but it seemed to me that scene was solid, that Eastwood caught the truth of the relationship.

There is a chilling moment when Hoover’s mother, Judi Dench, tells him she will teach him how to dance, and that — referring to a school boy who had been outed for crossdressing (and had then committed suicide) — she would rather have a dead son than a “daffodil son.” One hears, in the mother’s words, the most ancient of primitive demands that the race must reproduce itself.

While Tolson never gives a sense of having political views of his own, he does, near the end of the film, as Hoover has completed his autobiographical notes, tell Hoover the truth. He tells him that he has read the book, that the notes are a fiction, that Hoover hadn’t personally made the arrests he had claimed, that it was not Hoover, but special agent Melvin Purvis who had tracked down Dillinger. (Hoover, jealous of Purvis’ role, had exiled him to a distant post).

It is a devastating but not vindictive setting straight of the record.

It is precisely because Clint Eastwood has made the sexual angle central to the film, without playing games with it, that the film is so powerful. We are able to see the corruption of Hoover (who loved playing the horses, and accepted the arrangements with the tracks that his bets always paid off), the racism, the fanatic fear of subversion, and yet to see the haunted man behind the throne of power.

This generation cannot easily conceive of the power the FBI held on the imaginations of the American public. And it was, to some extent, justified.

In 1954, as the U.S. was considering getting involved in the French disaster in Indochina, Maggie Phair and I, from the Socialist Party, had gone down to the boardwalk in Ocean Park late at night to stencil the slogan “Send Dulles, Not Troops, to Indochina.” (Dulles was then Secretary of State.) I had with me a slim folder containing the layout for a leaflet on Vern Davidson, a Socialist Party member then in prison for draft resistance, and some addresses of local contacts, and finally some totally non-political family snapshots, which were of personal value.

When Maggie and I were done, and I went to pick up my manila folder, it was gone. Clearly a theft, but one with few rewards. The next morning I called the FBI office in Los Angeles, and said that someone had stolen something of mine which, if the thief was patriotic, he would turn over to the FBI. The FBI (of course) denied any knowledge of the matter.

However a year or two later the photos that had been in the folder were mailed to me at my parent’s address — an address which hadn’t been on the folder. Score one for the FBI.

Two final points. I said earlier that I’d remark on the folly of the occasional acts of radical violence. The casual radical, the young radical “here on vacation,” can talk about using violence, bombs, sabotage, in resistance, ignoring that the history of such acts (which helped provide the basis for setting up the FBI) is always to give greater power to the State.

There is surely no one to whom radicals should pay more heed than Lenin, who warned against the “propaganda of the deed,” the folly of thinking the force of the State could be overturned by random acts of violence. All of history has shown that there is nothing easier to penetrate than a secret organization. Secrecy and violence play into the hands of Hoover and those like him.

The second final point is troubling and I offer it uneasily. No modern state can afford to be without some security apparatus. We can condemn the FBI, but we were also furious that it did not send its agents into the Ku Klux Klan. We know that the problems of organized crime and of irrational violence which can come as easily from the right as from the left (remember the Oklahoma bombing) require some agency of investigation.

The problem is how to maintain control over such agencies. I pose the problem; I do not have the answer.

Meanwhile, catch J. Edgar and see how dangerous the secret police can be, and how deeply they threatened our freedoms within very recent memory.

[David McReynolds is a former chair of War Resisters International, and was the Socialist Party candidate for President in 1980 and 2000. He is retired and lives with two cats on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. He posts at Edge Left and can be reached at dmcreynolds@nyc.rr.com. Read more articles by David McReynolds on The Rag Blog.]

Well done, David, well done. I’ve been wondering whether I wanted to see this film and you’ve explained that I should.

I think violence on our side leads to an obsession with secrecy that becomes toxic. In the cases of the Panthers and the American Indian Movement, killings of our own folks on allegations they were “spies.”

The nonviolent groups I worked with always assumed tapped phones and agents at meetings and frankly did not care. We had nothing to hide. Our demands were public and our tactics ditto, except for the occasional creative and individual act of vandalism.

There is need for an FBI.

There is need for a CIA.

One key to holding them in check is a constant push against governmental secrecy. They should have to justify every word they refuse to make public to a federal judge or someone with like authority.

A problem with both the FBI and the CIA is that in order to do legitimate work, they have to involve themselves with unsavory characters. This leads to a delicate judgment about when to blow cover for the purpose of prosecution, because it’s one of our fundamental rules that defendants have a right to face their accuser.

It isn’t easy to have an informant inside the KKK or a Mexican drug cartel, and you know that at some point the informant becomes a witness and from that point is useless. That call is not always clear except in the rearview mirror.

Hoover was a monster and I am uninterested in seeing a film which ‘humanizes’ him. It’s not clear from the McReynolds review but apparently Eastwood skims over COINTELPRO and other FBI campaigns which resulted in great harm to the nation and many individuals.

Hoover not only blackmailed public figures and wiretapped everyone –– including President Kennedy –– but used the FBI to wage his own brand of political warfare, something quite dangerous in a free society.

Hoover’s denial of the Mafia’s existence was not merely humorous but damaging; he and Tolson each summer spent a month as guests of the mob at Del Mar, and he made deals with mobsters which handcuffed legitimate law enforcement.

Hoover was also involved, at least as an accessory after the fact, in the murders of Martin Luther King, Jr. and John Kennedy. The Bureau was also probably behind the killings of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark in Chicago.

If Eastwood’s film glosses over these things, which it apparently does, then it would such a distortion as to render it dishonest as a biography.

McReynolds points out that younger generations would not be familiar with the darker side of Hoover, nor the specifics of his many crimes. A popular film which omits these things may be regarded as a disservice to them and to history.

I wondered about that, Richard. Hoover liked to bet on the ponies. The Mafia liked for Hoover to bet on the ponies. They let him win for a while. Then they sucked him into some real losses and he was theirs. After that he always denied their existance. He believed M.L. King was a communist. He believed it because he was a fool. He wiretaped every motel and hotel room King stayed in but when he listened to the tapes all he heard was bed springs squeaking and heavy breathing and Coryetta was nowhere around. One of the worst things about Hoover happened when L.Patrick Gray took his place. He looked at Hoover’s personal papers and immediately burned them. There must have been some really disgusting stuff there but we will never know. That would have been America’s one chance to see what the “land of the free and the home of the brave” is really made of. If Eastwood omitted all that he labored mightly and gave birth to a mouse.

Had mixed feelings about the film myself; agree with David about Eastwoods direction.

Towards the end of the film there’s a scene where Hoover manufactures a hate letter to King to blackmail him into declining the Nobel Prize. Atlantic says it didn’t happen; the Kennedy’s, esp. Robert were gung ho on going after King, Hoover gave him a measure of protection. Here’s the link – pretty good piece.

http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2011/11/what-really-happened-between-j-edgar-hoover-and-mlk-jr/248319/