The Rag Blog and Rag Radio present Jonah Raskin in AustinJonah Raskin will be our special guest at a Rag Blog Happy Hour, Friday, Oct. 7, 5-7 p.m., at Maria’s Taco Xpress, 2529 S. Lamar Blvd. All are welcome. And on Saturday, Oct. 8, Jonah will do book signings at Oat Willie’s Campaign Headquarters, 617 W. 29th, from 2-4 p.m., and at Brave New Books, 1904 Guadalupe, from 5-7 p.m.

Jonah Raskin will also be Thorne Dreyer‘s guest on Rag Radio, 2-3 p.m., Friday, Oct. 7, on KOOP 91.7-FM in Austin and streamed live on the World Wide Web.

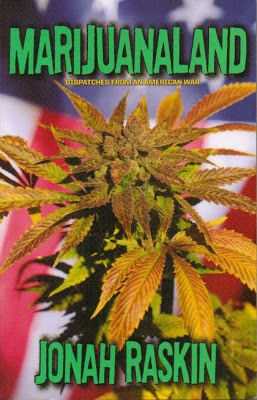

Marijuanaland:

Dispatches From an American War

By Mariann G. Wizard / The Rag Blog / September 29, 2011

[Marijuanaland: Dispatches From an American War by Jonah Raskin (High Times Books, 2011); Paperback, 154 pp. $12.95.]

Jonah Raskin has written about marijuana (cannabis) politics and culture since the 1970s. A professor at Sonoma State University in northern California, he teaches communication law and American literature and coordinates an undergraduate internship program. Jonah has authored 12 books, including biographies of Allen Ginsberg, Abbie Hoffman, and Jack London, and Field Days, about farm workers, organic farms, and farmers’ markets.

Outside academia, he created the story and characters for the stoner movie Homegrown, starring Billy Bob Thornton, Kelly Lynch, Hank Azaria, Ted Danson, and Jamie Lee Curtis. He’s a regular contributor to The Rag Blog and has written for the Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Chicago Reader, Village Voice, and the International Herald Tribune. Jonah also was active in the Sixties with the Youth International Party (YIPPIE).

I knew much of this before reading Raskin’s latest, Marijuanaland, but didn’t know he’d spent some growing-up years in the “Emerald Triangle,” the three California counties — Mendocino, Humboldt, and Trinity — that together produce some of the most legendary smoke grown, in great quantities and with the openness and civic pride of public harvest events much like Texas’ annual watermelon, peach, and other agricultural fests.

Jonah’s dad, a retired attorney who’d been a youthful rum runner in the waning days of alcohol prohibition, grew a personal pot patch after retiring to northern Cali, where young Jonah shared the sacred herb with his parents and others over the years.

In some ways, then, Marijuanaland is a personal memoir, a coming-home story by the smart young fellow who went to the city and became a hot-shot college professor, returning to his roots. As with most everyone who tries to go home again, there is some bitter with the sweet as he sees the effects of long-time-passing on parts of the once-immortal wilderness of youth.

Raskin connects the nickname “Emerald Triangle” with the equally-famed “Golden Triangle” of southeast Asia, where much of the world’s heroin originated before globalization really got rolling. He doesn’t mention the maybe-mythical “Bermuda Triangle,” where Atlantic and Caribbean meet Outer Space.

My own limited northern Cali exposure, however, made the connection clear to me. In Mendocino County, I visited the House of Hathor (chapel of the Egyptian cow-headed goddess); saw endless acres of blooming pink azalea forest, like a far planet in an old Star Trek episode; and lounged around quaint, politically-correct Mendocino-by-the-Sea, where there are no cell phone towers, the main grocery store is an organic co-op, and human carnivores are rare. Off-shore drilling is a constant threat to the spectacular coastline.

In Humboldt, mountainous roads wind through log-cabined communities where everyone knows everyone else, or give glimpses of hand-hewn estates clinging to impossible slopes. Forested hills go straight up and down, crossing coldwater creeks, and up and down again to rocky strands where the tide comes in fast through narrow inlets. Whalers and rum runners used these coves and foundered on these cliffs; crabbers and kelp-collectors use them still.

Vast Trinity County, northernmost of the three, remains virtually untouched by development. Mining, lumber, and ranching interests dominate the economy but leave most of Trinity unpopulated.

Since the 1970s or so the whole tri-county area has been the Hippie Heaven of the Western World, far as I know; where straight people try to act hip so as not to feel gawky. It’s a place where community runs deep. It’s a place where an outlaw can just about disappear.

Passage of California’s medical cannabis law, Proposition 215, in 1996, wrought many changes in the Triangle. Enormous profits in sales to cannabis dispensaries — themselves springing up on every corner, spurring zoning and licensing battles statewide — attracted a new class of growers, without local or even counterculture roots and devoid of ethics, wreaking environmental chaos in the primeval forest.

At the same time, increasing heat along the U.S.-Mexican border and completion of the infamous “border fence” south of San Diego pushed some enterprising Mexican pot growers to move to el Norte, cutting shipping and distribution costs and bringing their product closer to the consumer, growing in the national forests and other parkland in slash-and-burn fashion.

That both of these unpleasant results of partial cannabis legalization are due to its partiality is evident to serious observers. Demand for cannabis far exceeds its therapeutic or strictly medical use. The one inexorable law of capitalism is that demand produces supply; a law not subject to legislative or even popular repeal. California activists succeeded in 2010 in placing Proposition 19 on the November ballot, to legalize, tax, and regulate cultivation and sale of recreational cannabis in California despite continuing federal prohibition.

Marijuanaland, subtitled Dispatches from an American War, begins just as the campaign for Prop. 19 began in earnest and meanders through a year in the cannabis growing cycle, looking at marijuana-influenced culture, politics, economics, medicine, and law in the Emerald Triangle. Raskin visited with pot growers young and old, activists for and against legalization, newspaper editors, sheriffs, medical patients, healthcare providers, and friends-of-friends along the way. His quest ended as Prop. 19 went down to defeat and plants that had survived arbitrary annual raids on sun-drenched hillsides were harvested.

I’ve long known that the so-called “drug war” is a war of violence waged against certain drugs and people, but at first saw the subtitle as a kind of subculture marketing tool, like the full-color center section photos of spectacular plants, cured buds, and proud-but-headless growers in classic High Times magazine style.

But in the Triangle, the drug war is more than feds vs. heads. It’s long-time growers torn between a comfortable, rather smug “outlaw culture”; the prospect of lower profits and more competition balanced against legal status (a potentially enormous cost savings; many growers keep a lawyer on retainer). It’s sheriffs carefully timing raids to fall after most ganja has been harvested; who clearly know the folly of prohibition but love the shiny toys — helicopters, spy equipment, and such — the drug war offers its troops. It’s small town newspaper editors who think marijuana is evil and oppose legalization but pay the printer with half-page ads from pot defense lawyers.

As debate over Prop. 19 rose, some elected officials proposed copywriting trade names like “Emerald Triangle” much as wineries protect the names of their cultivars. In others, officials called for repeal of Prop. 215 and stronger enforcement.

Activists hedged their bets, favoring legalization for some growers but not others, especially not the newcomers from south of the border. There was deep division as well on specifics of Prop. 19, with some seeing it as a step forward, away from the current chaos, and others seeing the tax-and-regulate provisions as a cop-out, unworthy of support.

Some were suspicious because the initiative was first launched and supported not by a “traditional” marijuana advocacy group but by cannabis dispensary innovator Richard Lee of “Oaksterdam” (Oakland); others, sick and tired of “traditional” advocacy careerism, wanted change in their lifetimes.

Throughout the Prop. 19 campaign, public and private meetings throughout the Triangle revealed sharp divisions between those who felt themselves inundated with profit-seeking outsiders, local growers with or without vision and confidence, patients afraid of losing access to their medicine, and other interest groups.

Prop. 19 lost in the counties of the Emerald Triangle by as much as 3-1. A record cannabis harvest was hanging in the drying barns as votes were counted. Prices fell despite the defeat. Today, while marijuana is sold and smoked rather openly almost everywhere in California, the Drug Enforcement Administration continues to raid California’s legal medical cannabis providers and sheriffs continue selective enforcement against growers in rural areas.

If “the Garden of Eden is within you,” so is the Garden of Evil. The drug war, Raskin shows, is being fought in the hearts and minds of straights and stoners alike, where activists elsewhere like to envision a liberated zone.

Marijuanaland makes the pitfalls of partial legalization, profit-based politics, and widespread misinformation painfully clear. In the latter category is the book’s perpetuation of the myth that “Cannabis indica” is a separate botanical species from “Cannabis sativa,” the latter somehow inferior as a smoking herb.

From a botanical standpoint, this is hogwash; there is no agreement on whether indica is even a legitimate variety of C. sativa, but there is total agreement that C. sativa is one species much as Homo sapiens is; that is, any pot plant can (theoretically) breed with any other; since the plant is polymorphous, it has every evolutionary reason to remain one species, indivisible. Those who think otherwise contribute to outrageous retail prices for cannabis consumers; “indica” is but a marketing tool.

Raskin writes humorously of Triangle parents who work hard in the trade, make good money, and provide their kids every advantage in an area where non-marijuana-related income is limited. Whether the kids flee rural isolation for the city, “never to return,” or become low-achieving slackers content to smoke Dad’s weed and rodeo their ATVs through the forest, they’re bound to disappoint, at least for a while. Some things never change.

But the real crux of generational conflict on legalization is that some older users still think they’re part of a minority and fear change. Crying, “What about the children?” gains no traction against certain facts: the harm to children of having a parent jailed cannot be overstated.

Wherever cannabis use is decriminalized, use by teenagers drops substantially. And with 40+ years worth of kids like Raskin nurtured by pot-smoking parents in hundreds of communities all over the USA, demonstrably no more are bad apples than other youths of similar age and economic circumstance. The kids are, pretty much, alright.

The question America faces today is whether to cling to a world of scarcity and individual competition or find a new model of plenty and social cooperation. A huge majority of second- and third-generation “hippies” and perhaps of 20- and 30-somethings are creative, self-assured, resilient, tolerant, and determined to build the sustainable future we have utterly failed to leave them. The cannabis plant, in its entirety, offers a strong material basis for that future.

To move beyond even the present tug-of-war between state and federal authorities on voter-approved medical legalization, activists must launch more rigorous educational efforts and more successfully urge people out of the “emerald closet” of silent complicity. We must re-vision a world in which human beings love one another, respect the earth, and strive to relieve suffering in all living beings. Marijuanaland will offer many clues to the thoughtful on what is needed.

Cannabis is more than just a mildly naughty weed that makes flirting more fun, or a powerful medicine for pain and alienation. It isn’t just an endlessly renewable source of nontoxic fuels and fibers. Or the most nutritious food known to man. It is also a plant teacher, and until human beings recognize that there is other intelligent life on earth and heed its wisdom, we will bar ourselves from the Garden.

[Mariann G. Wizard (www.WordsWorth.biz ) is a Contributing Editor to The Rag Blog and longtime advocate of cannabis legalization (www.CannabisResource.com ). She regularly reviews and writes about medical cannabis and regulatory issues, among other topics, for the American Botanical Council. She volunteers and consults with the Texas Hemp Campaign and other legalization advocates. Read poetry and articles by Mariann G. Wizard on The Rag Blog.]

You may be preaching to the choir, but …

Right on, sister!

Bill, my brother, I just want the choir to sing out, loud and clear!

thanks!!

Marijuana the plant teacher. Good one. Sometimes I feel like we are destroying the earth because the voices of the plants are illegal. The plants that bring our consciousness to a love of life and the earth, the voice of Mother Nature herself, are illegal.

And so, not knowing better, we try to dominate her.