Bombs away:

Libya, NATO, and international law

By David McReynolds / The Rag Blog / July 13, 2011

The original UN resolution, pressed for by France, Great Britain, and the U.S. (all three led by men who have never been in armed combat) was to use such force as was needed to protect the civilian population of Libya. It was explicit that the NATO operation was not designed to force a regime change — though Obama has since made it clear that in his view Gaddafi must leave.

The events in Libya are tragic because they are a civil war, not part of the North African Spring. Far more violence has been used in Syria, with no word of NATO intervention. At last report Saudi Arabia had over a thousand troops “loaned” to Bahrain, with no hint of NATO intervention. What makes Libya different? It has oil.

I’m not writing a brief for or against Gaddafi. I am saying that NATO has violated the UN Resolution, that it should cease combat, and accept any of several offers put forward by other countries for an immediate cease fire. In particular the use of air attacks in a transparent effort to murder Gadaffi are completely indefensible.

But it is NATO which I want to look at first, and this carries us back to the early days of the Cold War. There have been books written on the origins of the Cold War but we have time only for a sketch. When WW II ended in 1945, it was won, in Europe, by the extraordinary losses of life by the Soviet Union. From the Western side there was a fear of the masses of Soviet troops and tanks and the reality of the mass Communist Parties in France and Italy.

The Soviet theory, at that time, not to be revised until Khruschev became the Soviet leader, was that conflict (and by this one assumed war) between capitalism and communism was inevitable. The one ace in the hole of the West was the nuclear bomb, and the speed with which the U.S. surrounded the Soviet Union with air bases which would make possible nuclear strikes deep in Soviet territory.

From the Soviet side, their massed troops were exhausted, the lines of communication made any serious attack on the West impossible. What the Soviets did want — what would have been true of any government in Moscow, regardless of its politics — was a buffer zone between Russia and Western Europe.

Russia has no natural defenses, no oceans, no rivers, no mountains. It had suffered from the Napoleonic invasion in the 19th century and from two German invasions in the 20th century. The Soviets sought at first to gain security through getting a U.S. and British agreement to a neutral Germany, along the lines that had been worked out with Austria and Finland. But in the climate of 1948 when nerves were raw on both sides and at a time when, possibly, wiser heads on either side might have changed the course of events, the Soviets moved to take control of Czechoslovakia, bringing it into the East European Bloc.

(There was an unintended tragedy here — in the last free elections in Czechoslovakia, the Communist Party had a strong share of the vote — the Soviet moves to bring it into the Soviet Bloc was a death blow to the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia).

The same year saw the raw testing of nerves when the Soviet Union cut off the land route from West Germany into Berlin, and the West responded with the Berlin Airlift.

Western Europe, essentially under the control of the U.S. (though a much gentler control than Eastern Europe faced from Moscow) responded to events in Czechoslovakia and the Berlin crisis by establishing the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) — a military defensive shield. That was in 1949.

Western Europe, essentially under the control of the U.S. (though a much gentler control than Eastern Europe faced from Moscow) responded to events in Czechoslovakia and the Berlin crisis by establishing the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) — a military defensive shield. That was in 1949.

The Soviets established the Warsaw Pact in 1955, several years after the founding of NATO. The Soviets had waited, still hoping for some kind of demilitarization of Germany, but this hope was ended when West German military forces were admitted to NATO in 1954.

In theory (and in the eyes of almost everyone in Europe), the two military pacts were “mutually defensive pacts.” But it was Professor Johan Galtung, a Norwegian academic (and pacifist — who served time in prison rather than doing military service) who advanced a theory I think proved more accurate.

Galtung felt that the NATO and WARSAW pacts were never intended to protect from outside forces (ie., the West realized Moscow was in no position to send forces into Western Europe, while the NATO forces knew that massive public opposition would make it untenable to invade the Warsaw Bloc). Rather, Prof. Galtung suggested, the two pacts were designed for “vertical control.”

If one goes back to that period there is a great deal of evidence of plans by the U.S., and by the military and police forces in France and Italy, to prevent even a free election of the Communist Parties in those countries, and to use NATO forces to achieve this — ie., a “vertical control”

Looking to the East the examples abound. On June 17, 1953, there was a major workers’ uprising in East Germany, put down with Soviet military forces, with at least 125 killed. In Poznan, Poland, in 1956 there were substantial working class riots, put down with Soviet forces, with something close to 200 people killed. Finally, and most dramatically, in Hungary, in October of 1956, there was a revolution which overthrew the government.

The Soviets at first agreed to withdraw and permit the formation of a new government, but then sent in troops. It is estimated that at least 700 Soviet troops and 2500 Hungarian were killed. (Matters were not helped by the fact that in October, 1956, when the world should have been focused on Hungary, Britian, France, and Israel invaded Egypt to seize control of the Suez Canal — a lesson reminding us that workers should never look to imperial powers for help at a time of need!).

It was at this moment when, if more rational minds were in control in the West, the leaders of NATO would have put through a call to Moscow saying “Look, it is obvious that the Warsaw Pact cannot possibly attack us — you can’t even control the countries in your own bloc. So we are now, unilaterally, dissolving NATO and we urge you to join us, and together see if we can work out some plans for genuine demilitarization of Europe.”

But rational minds were not in control. Even when the Soviet Union itself collapsed in a remarkable series on nonviolent revolutions, the West did not say, “Hey, we don’t need NATO anymore — the Warsaw Pact has dissolved, and our only excuse for existing dissolved with it.”

No, the “realistic” political minds in Washington, Paris, London, and Bonn began to talk of ways of finding new functions for NATO, admitting the nations that had been under Soviet control, and pushing the Western military machine closer to Russia’s borders. Part of this is the fulfillment of the sociological law that no organization goes quietly into the night.

When the March of Dimes realized it had won the fight against polio, it didn’t dissolve — why dissolve when so many people had jobs? They just found a new disease. NATO provides all kind of jobs for Generals and for ordinary bureaucrats in Brussels. To dissolve NATO might threaten the survival of Brussels itself.

And so NATO found new purposes. It deployed military forces to Afghanistan! A most remarkable deployment, since not one of the countries in NATO (with the exception of the earlier ill-fated British Mission) had ever even been to Afghanistan. A new war! A new purpose! No need for generals to find honest work! The bureaucrats at Brussels were safe!

So in this sense it is not surprising that NATO, finding itself firmly locked out of events in North Africa, not invited to play a key role in Tunisia or Egypt or Bahrain, decided it could play a role in Libya, and at least Libya had oil!

My first point has been that NATO — an organization which probably should never have been formed, and which in any case was formed entirely in relation to tensions in the middle of the 20th century — should be dissolved now. It should have been dissolved long ago. “Out of NATO” should be the slogan of every socialist and peace group in the NATO bloc.

The second point is international law, which has surfaced since the European courts issued a writ for the arrest of Gadaffi. I do not know if Gaddafi qualifies for the writ — there is much that I don’t know. But I do know that former British Prime Minister Tony Blair qualifies for such a writ, as does the former President of the United States, George Bush. I write this not because I have a special dislike for Blair or Bush, but because the force of law must carry with it some element of logic.

I am very glad that some of the surviving leaders of the Khmer Rouge are being brought to trial. But even in that case I am worried over the process by which the international courts selected who should be prosecuted. All scholars who have followed the deep tragedy of Cambodia know that both China and the United States maintained support for the Khmer Rouge long after the Vietnamese Army had driven it from the cities. Scholars of events in Indochina know that it was the CIA action in installing Lon Nol in Cambodia, which in the process, drove the King from his throne, and opened the door to the Khmer Rouge. Again, scholars know the the heavy air attacks on Cambodia, ordered by Kissinger and Nixon, gave the Khmer Rouge a legitimacy. Nixon, of course, is gone, But Henry Kissinger still makes guest appearances on TV shows. He is still a paid consultant for at least one network.

In no way am I trying to excuse the former leaders of the Khmer Rouge from their day in court — Cambodia deserves no less. I have been to Cambodia. I have seen the death pits, the skulls with the bullet holes. I want justice.

But the “trick” of international law is that if it is too obviously selective — in the case of Cambodia we have only four Cambodians on trial — we are surely mocking the dead, and in the process, using that trial to mock the law itself.

And if — with the memory of Iraq on our minds, and knowing all that we know about it, knowing all the civilians in Iraq who were killed, all our own men and women who were killed, or who bear injuries that will twist their minds to the final days — if, given those realties, we bring in a writ only against Gadaffi, does this not turn international law on its head?

Turning to Libya. To admit I do not know enough about Libya, is not to say I know nothing about it. Sheila Cooper, a friend of mine and a woman who liked secretarial work, had been secretary to Peggy Duff, also a good friend, and a leader in the British (and international) peace movement. Of Peggy, Noam Chomsky said she was “one of those heroes who is completely unknown, because she did too much… she should have won the Nobel Peace Prize about 20 times.”

When Peggy died in 1981, Sheila took a secretarial job in Libya. The pay was good and she hoped to make enough to retire. I was in touch with Sheila about Libya, she never conveyed a sense of living in a dictatorship, she chatted about the differences among the Libyans depending on what part of Libya they were from. Sheila, sadly, died of cancer before her retirement, but on the one occasion when I visited her in London, while she was on leave, she did not express any sense of horror or dismay about Libya.

Most of us who are old enough to remember World War II know of Libya from the surge of Allied or Nazi tank battles across the desert, or from an old Humphrey Bogart film set in Libya. What we don’t know is that the Nazis, Italians, British, and American armies left vast numbers of land mines behind, but never gave the Libyans the maps which could make possible finding the mines. As a result, even when I visited Libya in 1989 there were still farmers being blown up somewhere in Libya almost every week.

Most of us who are old enough to remember World War II know of Libya from the surge of Allied or Nazi tank battles across the desert, or from an old Humphrey Bogart film set in Libya. What we don’t know is that the Nazis, Italians, British, and American armies left vast numbers of land mines behind, but never gave the Libyans the maps which could make possible finding the mines. As a result, even when I visited Libya in 1989 there were still farmers being blown up somewhere in Libya almost every week.

Nor do most of us have any idea of the patriotic struggle of the Libyans against Italy. We may be aware that the name of Libya’s leader, Gaddafi, is spelled several different ways. The Libya we know today came into being in 1969, when Muammar Gaddafi took power in a coup, overthrowing the monarchy. But already oil had been discovered and Libya, which had not held much interest to other countries (the exception would be the U.S., which had a major air force base at Wheelus, Libya), was suddenly very much “on the map of world politics.”

(This was not the first contact the U.S. had with Libya — in fact, the first U.S. foreign military action was in 1805 in Tripoli against the “Barbary Pirates.”)

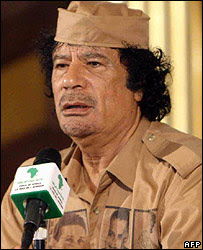

One of the first things Gaddafi did was to expel the U.S. from Wheelus — something for which I don’t think the U.S. has ever forgiven him. Libya, under Gaddafi, entered world politics in ways that are confusing. I have a good friend who thinks he is insane. Certainly, with his strange ways of dressing, it is obvious he is not your ordinary political leader. He holds no title, and while he is considered a dictator by his opponents, I think our problem is trying to find some way to think about Libya and Gaddafi — and it is hard.

Shortly after taking power he changed the name of Libya to “Jamahiriya,” an Arabic term generally translated as “state of the masses.” Gaddafi did not line up, politically, with either the Soviet Union or the Peoples Republic of China. Instead, he wrote the Green Book, of which I had a copy at one time but found close to incomprehensible and have (I think) lost it.

Remember, he was only 26 when he took power, he found himself in charge of a country which had, almost overnight, moved from being one of the poorest to being one of the most wealthy. He used that wealth to build universities, housing, medical centers. The form of government was — in theory — to be based on “direct democracy” without any political parties, governed through local popular councils named “Basic People’s Congresses.”

Clearly he had to have had considerable charisma to hold things together, and he seems to have hoped that his views, as set forth in his Green Book, would be a guide for the Third World. The best we can do in trying to translate “Jamahiriya” into English is to say it can be rendered as “Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahirya.” And that really leaves us more confused than before!

Gaddafi’s foreign policy has been, at best, erratic. He has extended financial aid to a wide range of groups, acted as a friend to people such as Idi Amin, given aid to the Irish Republican Army, supported armed Islamic rebels in the Philippines, etc.

At some point in the early 1980’s (I don’t have exact notes) I got an invitation to a conference on Peace and Liberation to be held at Malta. I checked with my friend Sheila Cooper, and she said the Libyans had asked her for any names that she could think of — and she had sort of turned over her address book. In addition to me and Daniel Ellsberg, there was an old friend from the independent left movement in Japan, a woman from Yugoslavia, two people from the Fellowship of Reconciliation in the U.S. — perhaps two dozen in all.

My guess that Libyan money was behind it was true enough — we had to raise the air fare to get to Rome, but from there we had tickets to Malta, and our costs in Malta were covered. The one real give-away was the huge table with Gaddafi’s Green Book.

There were only about four Libyans present for the conference, they did not “guide us” to any conclusions. I was interested that there were no representatives from the World Peace Council — the Soviet Union’s front group. It was clear that this was an experiment in trying to reach out beyond the usual group. My own feeling was that the money spent on us was at least not spent on Irish terrorists.

In 1989 the Fellowship of Reconciliation sent a team, including myself, Virginia Baron, an academic — Dirk Vandewalle — and a half dozen others for a week to take a look at Libya. Having Prof. Vandewalle with us was very helpful, as he could give us what clearly Obama needs and doesn’t have — a short course in the history of Libya.

We did not meet Gaddafi, but we met with pretty much all the key people in government. But even to say that is tricky. I realize much has changed since 1989, but there were no civil associations as we would know them, no trade unions, no lawyers associations, no political parties. The question of “how” decisions were made was not clear.

None of us found the political climate oppressive. Our hosts were frank and easy in their talks with us, we visited Tripoli without any “minders,” and had a chance to see some of the real wonders of the ancient history of Tripoli. And of course we saw the home of Gaddafi, which was hit, on orders from Reagan, in revenge for Libya’s alleged involvement in a bombing in Berlin.

(Proof of that involvement is sketchy — but the impact of the U.S. bombing was very clear. Not only had one of his daughters been killed, but we saw a part of the French Embassy which had been hit, and an apartment building in a clearly residential neighborhood which had been totally destroyed, along with everyone in it.)

The only contact I had had since was indirect. Someone I’ve been in email contact with, an American, had gone to Libya recently for a job, and then when the “troubles” began early this year, she had to leave, but in her notes to me after she left she expressed no sense of horror at Gaddafi — nor any great love for the man. She said that he probably had a fair amount of popular support, wryly noting that even Nixon won two free elections.

The most painful link to Libya was the Lockerbie bombing, since two good friends of mine lost their daughter — their only child — who was on the plane when it was destroyed. There are arguments about whether the Lockerbie bombing was actually the responsibility of Libya but the fact is that Libya had been the source of funds for terrorism (or, if you look at it from the Libyan standpoint, the source of funds for various struggles for national liberation). There is also no question that Libya had, on at least one occasion, sent out hit squads to silence Libyans who had left Libya but remained openly critical of Gaddafi

One does need to remember that the late Soviet Union did the same thing, Israel has done this, and I’m afraid the U.S. has also had a hand in this miserable game.

What is interesting is that in recent years Libya seemed to have made a major change in policy, settling British claims over the Lockerebie bombing, agreeing to end any further research into nuclear or other weapons of mass destruction. It is this most recent period that I know so little about — but how strange that Gaddafi and Libya would now have moved to the top of a hit list.

Two things are clear. This is not a revolution but a Civil War. I don’t know what forces are involved among the “rebels” but how little real support they have is provided by the fact that months after the French, British, and Americans have destroyed any Libyan air force, and after the murder of one of Gaddafi sons, and repeated attacks on his various compounds, Gaddafi is still there, he has been seen in public, he has received foreign guests, and Tripoli remains in his hands.

It is not surprising that various officials have “defected” since I think any of us might consider defecting as we realized guided missiles are being sent to track down key officials. This is less an appeal to a moral reason to leave the government, than an urgent sense of survival.

The other thing which is clear is that the rebels have also killed people. In one case (documented from press reports) the rebels admitted to having killed a number of prisoners of war they had captured “because they were black and we assumed they were hired killers.”

Civil wars are very nasty things. We lost more men in our Civil War than were killed in almost all our wars combined — WW I, WW II, and the Korean War — until late in the Vietnam War the total military dead was greater. We lost those men from a much smaller population. Civil wars are not civil. This one is tragic and we should be urging the European forces to rush to the negotiating table.

Certainly the Libyan adventure is one very good reason not to leave NATO in existence — it is a weapon that has already killed many in Afghanistan and may yet kill many more in Libya.

[David McReynolds is a former chair of War Resisters International, and was the Socialist Party candidate for President in 1980 and 2000. He was recently the subject, along with Barbara Deming, of a dual biography by Martin Duberman titled A Saving Remnant. He is retired and lives with two cats on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. He posts at Edge Left and can be reached at dmcreynolds@nyc.rr.com. Read more articles by David McReynolds on The Rag Blog.]