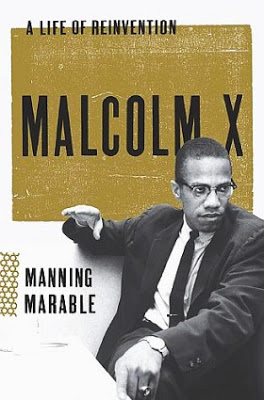

Manning Marable’s

Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention

The Malcolm he depicts is unquestionably, accurately, and thoroughly the Malcolm I knew.

By Tony Bouza / The Rag Blog / July 11, 2011

[Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention by Manning Marable (Viking, 2011). Hardcover, 608 pp., $30.]

Any reviewer owes the reader an accounting of possible biases, personal knowledge or connection, or any information helpful in assessing the worth of the analysis.

I was a detective in BOSSI (Bureau of Special Services and Investigations—NYPD) from July 1957 to December 1965 with one brief interruption in 1958. I rose to sergeant and lieutenant there and wound up writing a master’s thesis that became a book, Police Intelligence (an oxymoron?). It should never have been published because it wasn’t a book but a dessicated account of the unit’s operations. It contained a section on The Nation of Islam (NOI) and Malcolm X. The book’s turgid, soporific prose proved an unexpected boon to insomniacs.

I knew Malcolm X through my dealings with him over demonstrations, and I attended many, many street meetings at which he spoke — on Saturday afternoons at 125th Street and 7th Avenue. The heart of Harlem.

There was another level of operation at BOSSI — undercover infiltrations (American Nazi Party; Nation of Islam; many other groups) — in which I was only tangentially and periodically involved. I attributed this to an unspoken suspicion of my politics, but it was never expressed and never led to my deliberate exclusion. There was, of course, the additional factor that in a world of daily communicants who routinely referred to the cardinal’s residence as “One Powerhouse,” I was neither Catholic nor Irish enough. So I was episodically involved but never a central figure in the operations.

When I learned of Marable’s book my interest was piqued. I’ve always felt Malcolm X was a little understood — or even knowledgeably discussed — figure, although Spike Lee’s film was a real attempt at grappling with the central question of who murdered him and why. So I was a bit of a fly on the wall, but deeply interested and as involved as those who were controlling events allowed.

The book’s title is a good one because I’ve come to think of Malcolm as having lived three lives — a street thug, a NOI minister, and an integrationist, for wont of a more satisfying word.

Malcolm X must be understood within the context of the two major strains flowing through the black experience — integrationist and separatist. Thus, you have Booker T. Washington versus W. E. B. DuBois; A. Philip Randolph and Marcus Garvey; Frederick Douglass and Nat Turner; Elijah Muhammad and Martin Luther King, Jr.; Jesse Jackson and Louis Farrakhan. Malcolm X straddled both camps as a separatist (NOI, which demanded five states for its own nation, and the inclusive Organization of Afro-American Unity).

My final personal revelation is that I performed what I considered the very unprofessional act of attending Malcolm X’s funeral and passed by his open casket.

The book

Marable is appropriately dismissive of what is actually Alex Haley’s “Autobiography” of Malcolm X. No one I know seriously considered it the putative author’s true views and feelings. It was mostly seen as a very creative and skillful example of Haley’s take.

Marable’s clear desire is to demonize the police. He cites the FBI, but they were peripheral. The real monitor of Malcolm X’s behavior was BOSSI. His analysis is naïve, superficial, reflexive, and predictable. The reality may prove more nuanced and, perhaps, even more reprehensible, but history is a demanding taskmaster.

The author’s descriptions of Malcolm’s early life reflect careful research, objectivity, and a historian’s effort to avoid hagiography. The descriptions of Malcolm’s likely involvement in some homosexual adventurism can only be described as intrepid and commendable.

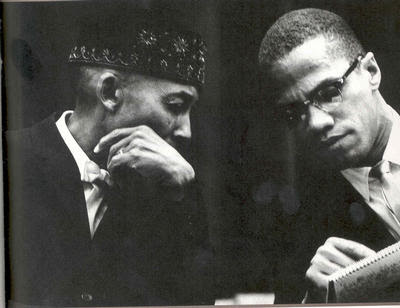

Marable’s description of Malcolm’s conversion to NOI is a triumph of research and smooth writing. Its objectivity is clear in the fair treatment accorded Elijah Muhammad’s early involvement in the NOI, especially given his later treatment of the hero.

The author’s willingness to describe Malcolm’s early forays into anti-semitism — a virulent stream in the black community sometimes surfacing as in Jesse Jackson’s reference to NYC as “Hymie-town” — is another reflection of his devotion to authenticity. I personally heard, in the Sixties, Malcolm refer to “Goldberg” in his withering tirades on Harlem’s corners.

Given the involvement of Jews in every facet of the civil rights struggle, this prejudice seems both unwise and perverse. It was, for example, two Jews (Goodman and Schwerner) who were killed with Cheney.

The author holds that the police (BOSSI/FBI, etc.) misjudged the threat posed by the NOI, describing it as “conservative, capitalistic and not really dangerous.” This ignores the profoundly subversive nature of a sect that professed and practiced separatism and hatred of whites, and also demanded its own nation. The NOI was and — though diminished — remains alienated and hostile. Louis Farrakhan, in 2011, praised Libya’s Muamar Qadaffi, who’d made a large contribution to the NOI.

In September 1960 Fidel Castro visited the United Nations and stayed at the Shelburne Hotel in midtown. Miffed at being denied an exclusive interview, New York Daily News reporter William Federici published a sensational account of “chicken pluckings” in the room by the Cuban entourage. This dramatic depiction served the cartoonish interests of an increasingly hostile readership and received international circulation. The Cubans did cook in the rooms but did no chicken plucking.

Incensed, the entire delegation moved to the Hotel Theresa in central Harlem, where Fidel was visited by the USSR’s Nikita Krushchev. Castro added to his move’s appeal to Harlemites by flying in his black army commander, Huber Matos, for very quick public appearances. Author Marable makes no reference to this source of Castro’s pique — a significant error. I was a part of the security detail there and had even engaged Fidel in vigorous conversations since his father and I had been born a few miles apart in Northern Spain.

Castro was irresistibly charismatic and winning.

Much is made of BOSSI’s intense focus on the NOI, but the author apparently didn’t know that equal attention was being paid to its counterpart — the racist, separatist American Nazi party. In a fatally ironic denouement, the men figuratively standing next to both Malcolm X and George Lincoln Rockwell (the Nazi leader) when they were murdered were both BOSSI operatives.

Would Marable’s ultra bleak view have been tempered knowing that BOSSI was an equal opportunity infiltrator? Perhaps not.

The author repeatedly reveals what I believe to be an over-reliance on NOI documents and, particularly, the probably unprecedented access granted by Louis Farrakhan, too central a figure in this controversy to be relied upon.

In An American Dilemma, Gunnar Myrdal, a Swedish sociologist, described our nation’s number one issue as the “Negro Problem.” In reality, over 70 years later, it still is, only now embodying issues of class as well as race. Despite undeniable and admirable progress since the watershed Civil Rights Act of 1965, black Americans continue to constitute the bulk of the underclass. After two and a half centuries of slavery and 100 years of Jim Crow we now address the problem with prisons.

Blacks naturally, resented and resisted this subjugation and expressed their anguish in crime, protests, separatist movements, and demands to be fully integrated. Marable echoes Myrdal’s views perfectly as he speeds to the crisis of Malcolm’s life and its end on Feb. 21, 1965.

But a clear understanding of that still mysterious assassination is absolutely central to any evaluation of this seminal work.

In the early ’60s Malcolm X’s position, nationally, was awkward. Whites largely saw him as representing the extremes of black disaffection, which helped them understand the more nuanced views of integrationist blacks.

His effectiveness as a speaker was remarkable. He related to, communicated with and responded to his audiences in what could be likened to a masterful composer’s interaction with a talented orchestra. I’d seen him sway, move, guide and undulate with street groups in a spirit of perfect symbiosis. He was indisputably Harlem’s greatest street orator, in an area and an era where I’d heard some memorable dithyrambs.

Malcolm’s break with the NOI is central to any understanding of its aftermath. To his last day in the NOI he was slavishly devoted to Elijah Muhammad and consistently extolled his master. Not one deviant or disloyal act could be cited. The author documents this persuasively.

Malcolm had been uttering incendiary indictments of White America in all its iterations, without inhibitions. His casual reference to Kennedy’s assassination on Dec. 1, 1963, only a few days after the event, was seen as being of a piece with every other of his utterances and unremarkable. The “chickens coming home to roost” was a pretty tame commentary by his standards.

Malcolm’s prominence, growth, and frequent referrals as “number two” had created inevitable rivals among a numerous Chicago coeterie anxious to succeed the prophet. Malcolm was suspended for 90 days. He accepted his punishment without question or criticism.

Those of us in the police world, watching NOI grow into a menacing separatist and, yes, subversive organization, were delighted by the split.

Pure serendipity that the NOI would throw away its greatest asset in a tawdry battle of succession among the Chicago clique that would, in a supremely ironic twist, be won by an outsider — Louis Farrakhan. He inherited and presided over — for decades — a diminished empire.

Malcolm accepted his fate with a clear hope of restoration. The hope soon faded. Clearly there was more to his suspension than a fairly tepid quip. What seems clear — from this book and our own assessments at the time — was that Malcolm was expelled to remove an obvious rival to power by those around Elijah Muhammad.

Marable makes clear that in early 1964 Malcolm and the NOI had stumbled and staggered to a separation inevitably turning permanent. This led Malcolm into a desparate search for a role in a play in which he was a star without a script, a national figure without platform or income.

The author states that despite threats, a history of some violence and actual references to a plot, the police did not believe he was in imminent danger. I can verify this since we were watching developments carefully and assessing the risks. We had agents in NOI and with Malcolm.

Malcolm’s life of a predictable slide into crime and drugs — made inevitable by a racist society in which the overclass denied its involvement in his fate — was, to coin a phrase, arrested by his NOI epiphany. This armed him with the intellectual and oratorical weapons that would launch him into national leadership.

His 1964 hajj to Mecca served, albeit however briefly, to greatly broaden his understanding, message, and influence. The NOI was an indefensible intellectual cul de sac from which he had to emerge to gain the relevance necessary to catapult him beyond the pigeon hole of racist freak.

Breaking with the NOI was one thing, denouncing Elijah Muhammad’s serial siring of children by NOI secretaries was another. This struck at the very core of NOI’s integrity and legitimacy. It could not and would not be brooked. The leader’s virtues could not be assailed. The Rubicon had been crossed.

Knowing this, we in BOSSI were perplexed. Assigning platoons of cops to cover Malcolm’s events was easy enough and routine but spasmodic and ineffective.

Assigning detective body guards 24/7 would be prohibitively expensive. I thought Malcolm would scorn a police offer of security but suggested we do so. Besides, we had an undercover agent — Gene Roberts — with Malcolm and this should help with Malcolm’s safety. Coverage was offered and promptly rejected by Malcolm. There is, in all likelihood, a record of this in BOSSI files.

The NYPD would never purposely endanger one of its agents, but the risk of Robert’s safety was weighed and accepted. It was an enormous piece of luck that he escaped injury on Feb. 21, 1965, at the Audubon Ballroom.

But now, with Muhammad’s denouncement as a matter of record, we all, Malcolm included, knew he was in mortal danger. Marable writes that Louis X (Farrakhan) wrote on Dec. 4, 1964, in Muhammad Speaks, “Such a man as Malcolm is worthy of death.”

Yet Marable, obviously grateful at being flattered by Farrakhan’s help and attention when it came to this book, and 45 or so years later, quotes Farrakhan’s “love for Malcolm,” describing him as “my brother.” Crocodiles are described as shedding tears as they consume their prey.

The NOI, with its discipline, its cadre of men accustomed to the uses of violence, and its own internal culture of brutal methods of correcting the behaviors of its targets, was a perfectly natural weapon to employ in carrying out organizational objectives. The period of late 1964 to early ’65 saw repeated incidents of bloodshed and even deaths surrounding the clashes inspired by Malcolm’s break/expulsion from the NOI.

The loss of Malcolm was a huge organizational disaster for the NOI, but the hubris at the top blinded them to its consequences. Marable describes the issues cogently.

He makes a really serious mistake when he cites BOSSI Detective Gerry Fulcher as saying the police brass “had the mentality of wanting an assassination.” This is an outrageous falsehood and undermines an otherwise impressive effort. I knew Fulcher and considered him a flake. My recollection, though dim, was that he was an ex-seminarian and so unreliable that we transferred him out. The notion of his serving as any kind of source is laughable.

We certainly viewed Muhammad and the NOI as the enemy but not Malcolm. We were delighted by his separation from NOI and certainly didn’t welcome the prospect — regarded as very real by us after he denounced Muhammad’s promiscuities — of his murder. And his move to a more conciliatory and cooperative posture certainly heartened those of us observing him closely.

Malcolm’s charisma, intelligence, courage and effectiveness were qualities we all could admire. My attending his funeral was really a mark of the genuine regard I had for him and my views were shared by my colleagues.

Malcolm’s assassination on Feb. 21, 1965, in a packed ballroom of the Audubon Auditorium, resulted in a thoroughly confused police investigation that netted three killers from the scene and little else. The truly guilty — not the shooters but those who sent them — escaped all accountability.

The investigation was botched.

With the benefit of hindsight and acknowledging the reality that there’s never been a police mistake I haven’t or couldn’t have made, what would a real inquiry look like?

A task force of about 10 investigators should have been created, composed of BOSSI detectives, homicide sleuths (traditionally the best), and fire marshals. The focus would be on the firebombing of Malcolm’s house days before his murder and the murder itself.

The firebombing may well have rendered clues like fingerprints on the molotov cocktails and such. Then the murder itself and trying to leverage the possibility of long sentences into cooperation from the shooters. There needed to be a more thorough search for the actual perps and then an inquiry into their backgrounds.

The central aim of it all would be to really establish the roles of Captain Joseph X Gravitt, Minister Louis X Farrakhan, and the prophet himself, Elijah Muhammad.

The utter failure of the NYPD created a dismal history and the principal losers have been the black community itself. A parallel tragedy lies in the NYPD’s obvious stonewalling of any release of records likely to help our understanding. I need to add that I cooperated with the press, always, in its attempts to inform the people.

The chaotic scene and the determined silence of those accused didn’t help.

The historical and traditional view of the causes of black martyrdom center on the metaphor of a lynching — whites killing blacks. Malcolm’s murder was different and created a dilemma not confronted by his community even almost half a century after his death. He was killed by blacks.

Marable cites Farrakhan as the principal beneficiary and as Betty Shabazz’s prime suspect, even years later. But the principal focus must center on Elijah Muhammad, and the motive — we all thought then and I do now — was Malcolm’s references to Muhammad’s having fathered six or seven children by his secretaries.

The author’s masterful, scholarly, writerly book is unnecessarily weakened by reliance on a source like Fulcher — and the absence of more authoritative possible sources within BOSSI such as its commander or Detective Roberts or his handlers. The lack of really valuable sources forces the author into the arms of unreliable or mendacious alternates.

It is, withal, a must read.

The Malcolm he depicts is unquestionably, accurately, and thoroughly the Malcolm I knew. It is a wonderfully useful evocation of the man and a sure and certain guide to understanding the icon that was Malcolm X.

But it ain’t the final word.

[Anthony V. (Tony) Bouza was born on April 10, 1928 in El Ferrol, Spain. A 40-year veteran of municipal police including an extended stint as a New York detective, Bouza served as Minneapolis police chief from 1980 to 1989. He is the author of six books. This article was originally published at Southside Pride, a South Minneapolis monthly. Southside Pride editor Ed Felien is a regular contributor to The Rag Blog.]

- Also see “John McMillian : For Manning Marable” / The Rag Blog / April 7, 2011

Not sure how reliable above article is. Betty Shabazz, for example, apparently denied that police “coverage was offered and promptly rejected by Malcolm” prior to his assassination. Also see following excerpt from Roland Sheppard’s June 9, 2006 Socialist Appeal site article:

“I witnessed Malcolm X’s assassination at the Audubon Ballroom, on February 21, 1965. I am writing with the benefit of first hand knowledge of what took place that day…

“There is no doubt that the police had plainclothes officials in the audience. As a witness to the assassination, I was questioned at the Harlem police headquarters. I recognized a man there – obviously a cop, with free run of the office – whom I had seen sitting in the first row at the Audubon Ballroom where Hayer said his accomplices were sitting…. It would have been virtually impossible for only three people to have carried out the assassination…

“I was told by Malcolm’s guards when I got outside the Audubon Ballroom, that two people were caught by the crowd at the same time and that one was taken to the hospital by the police and the other taken into police custody. Hayer was taken to the hospital and then booked. It is likely that the second man caught was the one running ahead of Hayer and was quite possibly an agent…

“…There were normally 30 to 50 cops, in their blue uniforms, both inside and outside the building stationed at all the exits. Escape would not have been easy.

“However, at the meeting when Malcolm was assassinated, the police were nowhere to be found—even though they knew that an assassination attempt was imminent. In order to plan Malcolm X’s death, the conspirators would have needed to know and be confident that the cops were not going to be there on that day…

“…From the very day that Malcolm X split from the NOI, the FBI worked on a day-to-day basis with BOSSI and the CIA to infiltrate and disrupt his activities. William Sullivan (subsequently of Watergate fame) was the FBI agent in overall charge of both the infiltration of the NOI and Malcolm’s organization, the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU).

“…A coordinated effort was carried out between all government spy agencies to widen the split between Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad, to increase tensions between their organizations, and to undermine their support among African Americans. It is also safe to assume that agents, informants, and provocateurs from these different agencies were sent into the NOI and Malcolm X’s organizations and that these agents were also present at the Audubon Ballroom when Malcolm X was assassinated. One of police informants, who later informed on the Black Panthers, told me as I was going to take my normal front row seat that “you are not going to sit there today,” and he had me sit in the front row on the left side of the Ballroom. (The assassins then sat in the area where I normally sat to hear Malcolm X speak.)

“…The government had the motive to assassinate Malcolm X and the ability, through its COINTELPRO spy operations, to orchestrate his assassination. It is now time to open up all the files of the CIA and the FBI, as well as the thousands of pages of files of the New York City Police Department, so that the truth about the assassination of Malcolm X can be exposed…”

Roland Sheppard is a retired Business Representative of Painters District Council #8 in San Francisco…. He was in charge of defense whenever Malcolm X spoke at the Militant Labor Forum in New York City from 1964-1965.

I haven’t yet read Marable’s book and am both perplexed and fascinated by the article; interesting, however reliable or not.

However, I will differ with Bouza and other reviewers who dismiss Alex Haley’s early “Autobiography of Malcolm X” as inauthentic. Regardless of whatever self-serving mythologies it may have served up from either Haley or Malcolm, the historic role of that book cannot be overestimated. It was a national best-seller at a time when white youth in segregated communities were becoming aware of having more in common with black youth than with white adults, and there is no way of knowing how many of those paperback books were avidly devoured by white kids like me. Just as we had suspected for a while now, here was dynamic, irrefutable proof that black people WERE equal, WERE oppressed, WERE capable of independent greatness, unsupported by the paternalistic authoritarians that we, too, despised.

Having read the “Autobiography” was for a time a sort of password to a club of intellectually and socially curious and idealistic people, people who, like Malcolm X, wanted to make a difference for humanity. Like Muhammad Ali at the same time and on another kind of gut level, Malcolm’s humanity was what made him beloved by readers of Haley’s book; we who they tried to teach that black people were less than human, less than G-d.

I know of more than one young man and woman today brought up on Malcolm’s words and the ideas he brought home from his Hajj first and foremost because of Alex Haley’s extraordinary book.

I find it fairly outrageous that the Rag Blog would print this apologia for the NYPD and BOSSI as its review of Marable’s book on Malcolm. If you believe that the NYPD looked favorably on Malcolm before or after his split with the NOI, I have a bridge in Brooklyn I can sell you cheap. The idea that Malcolm became an “integrationist” or “more cooperative” (with whom? the NYPD?) after leaving the NOI and forming the Muslim Mosque and the OAAU is ridiculous. He continued to put forward revolutionary ideas, including the need for a Black revolution and for land; his ideological change had to do with becoming more internationalist, more explicitly anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist. I grew up in NY in the 50s and 60s as an Orthodox Jew and was aware of Malcolm as a public figure of great stature and integrity. He was not perceived as anti-Semitic — the big rupture between the Black and Jewish communities occurred after his death, and particularly in response to Albert Shanker’s racist response to the demand for community control of the schools. There is a classic picture of Malcolm smiling next to a subway billboard with the then ubiquitous slogan “You don’t have to be Jewish to love Levy’s Jewish Rye” which Malcolm specifically asked the photographer to take.

Bouza’s notion that BOSSI surveillance and infiltration of the Nazis justifies their COINTELPRO-type work on the NOI and Malcolm is also outrageous. The NOI with all their ills does not equate to the Nazi Party. And in fact, shortly after Malcolm’s death, the American Nazi Party and the NYPD Patrolman’s Benevolent League (PBA) jointly and openly led a campaign to overturn and abolish Mayor Lindsay’s Civilian Complaint Review Board.

Michael, this is not “The Rag Blog’s review of Marable’s book on Malcolm.” Please see Rick Ayers’ and Harry Targ’s reviews:

http://theragblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/books-rick-ayers-marables-malcolm-bio.html

and

http://theragblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/books-harry-targ-remembering-malcolm.html

as well as John McMillian’s piece about Marable:

http://theragblog.blogspot.com/2011/04/john-mcmillian-for-manning-marable.html

We thought Bouza provided an interesting perspective and figure our readers are smart and sophisticated enough to read it and come to their own conclusions.

We have run multiple pieces on Marable’s book because we think the book — and Malcolm’s story — are so important and relevant to our times.

Thorne