The Greece case is a victory for all Christians who need the government to endorse their religion, who have too much faith in the government and not enough faith in their chosen religion.

Heavens looking down on Supreme Court building, Washington, D.C. Photo by Saul Loeb / AFP / Getty Images.

“The separation of church and state has been a cornerstone of American democracy for over two hundred years,” said Justice Samuel Alito, writing for the majority. “Getting rid of it was long overdue.” — Satire by Andy Borowitz in The New Yorker

SAN MARCOS, Texas — The U.S. Supreme Court has now given public officials in the U.S. clear permission to promote and propagandize for the religion of their choice (mostly Christian), as well as religion in general, while performing their public duties. Five justices, all Catholic (one other Catholic opposed the decision) made up the majority in Town of Greece v. Galloway, decided on May 5, 2014. How this ruling can afford equal protection for everyone has not been explained.

The decision, its Analysis, and the reaction

In the Greece decision, the Supreme Court interpreted government-sponsored religious practices by private individuals as personal expressions of speech, rather than as the government-sponsored acts that they are. In the Court’s view, if a government-invited minister instructs us to stand, bow our heads, and pray with her, such instructions will not be attributed to the public officials who sponsor the prayers, and none of us are required to follow the religious instructions of the minister.

While there has never been unanimity in this country about government-sponsored prayers, the authors of the First Amendment recognized that Americans had the right to follow whatever religious practices suited them and that the government had no business promoting favorite or accepted religions at its official meetings, at which any of us might need to appear for a specific purpose or wish to attend because of our interest in civic affairs.

Justice Kennedy wrote the majority opinion in Greece, basing the decision on our purported history and on what the majority called the country’s legislative tradition of ceremonial prayer before the start of Congress and some state legislatures.

Ceremonial prayer is a trivialization of a religious practice that many hold to be sacred.

Ceremonial prayer is a trivialization of a religious practice that many hold to be sacred. Jim Huff, Secretary/Treasurer of Mainstream Oklahoma Baptists, explained this problem: “Prayer time is not to be used as a ‘gesture,’ or ‘tone setter.’ It is not to be used as a ‘social or political’ statement. It is not for ‘public relations.’ It is not an occasion to demonstrate ‘piety’ for others to see. Those reasons only trivialize prayer.”

Justice Kennedy’s opinion suggests that ceremonial prayer is an unbroken tradition beginning with the Continental Congress, which did convene itself once with a prayer quoted in the opinion. Annie Laurie Gaylor, Co-President of the Freedom From Religion Foundation, points out what Kennedy failed to acknowledge about government prayer, however:

The majority opinion… ignores the fact that the framers of our Constitution never once prayed during the four-month-long constitutional convention that produced our godless Constitution. If the framers didn’t need to pray over something as momentous as the national Constitution, why do local public officials need to pray over such mundane decisions as liquor licenses, sewers and variances?

The folly of the Supreme Court majority’s reliance on history and tradition as a constitutional standard in reaching its decision in Greece is obvious when we think of some of the historical and traditional abuses that were once standard practice in this country: slavery, Jim Crow, restriction of voting rights to white male property owners (excluding women and blacks for 140 years or more), segregation, prayer and Bible-reading in schools, religious commencement exercises in our public schools, the poll tax.

Further, Kennedy and the majority failed to appreciate the important differences between local government bodies, such as city councils and commissioners courts, and the state legislatures and Congress.

With these latter groups, opening prayers are directed to the legislators and not to the general public. With local governments, however, the prayers are addressed to those in attendance, as well as to the public officials making the decisions. In many cases, the person presiding at the meeting or giving the prayer instructs all in attendance to participate by standing, bowing heads, and even joining in saying “amen” at the end. Sometimes, public officials encourage participation by joining in the prayer themselves, which can be heard over the public address system.

Justice Kagan, who wrote a dissenting opinion for the four justices who disagreed with the majority’s reasoning, pointed out these differences, but the majority swept the differences under their judicial robes. The majority thought that no decision-maker would be influenced by a lack of religious piety in someone who was appearing before the body to ask for a favorable decision on some issue. They were unwilling to consider the very real fears that petitioners have that they will not be treated impartially unless they demonstrate religious views approved by the public officials. I know many people in Hays County (Texas) with just such fears.

The majority decision failed to consider the history of coercion associated with government sponsorship of religion.

In arriving at such a view, the majority decision failed to consider the history of coercion associated with government sponsorship of religion. For much of our history, Protestant Christians sponsored public religious practices as a way to create what was termed a “moral foundation” by David Sehat in his book The Myth of American Religious Freedom. That “moral foundation” was both coercive and exclusionary, especially toward Catholics, Jews, Mormons, freethinkers, and many others who faced active legal and social discrimination until the Supreme Court began dismantling the entanglement of religion and government nearly 75 years ago.

Over and over again, Justice Kennedy’s opinion demonstrated how out of touch with the realities of living in America the majority is. For Kennedy, when city or county officials invite mostly Christian ministers to pray before their meetings, they are merely “acknowledging the central place that religion, and religious institutions, hold in the lives of those present.”

Only someone steeped in Catholicism, as all of the majority’s members are, could be so obtuse. With 20% to 30% of the adult population professing to be nonreligious, it is dishonest to pretend that all citizens at a local government meeting find religion a central part of their lives, when they are attending because of an interest in issues like zoning, streets, water, law enforcement, sewers, and environmental regulation.

Hays County government prayer practices

Like the prayer practices of the city council in Greece, New York, which began in 1999, the prayer practices of the Hays County Commissioners Court and the City of San Marcos are relatively new. Right-wing Christian extremists introduced Christian invocations in Hays County in 1998, led by then County Judge Jim Powers. The right-wing, evangelical mayor of San Marcos in the early 2000s, Susan Narvaiz, introduced invocation prayers to that body. Previously, there is no record of prayers at Hays County or San Marcos governmental meetings.

Not as extreme in his religion as Powers was, current County Judge Bert Cobb has opened the Commissioners Court to prayers from one non-Christian religious group. A representative of a Hindu Temple in northern Hays County has given the opening prayer at meetings two or three times in the past two years. But Judge Cobb’s practice does not comply with the Greece ruling entirely. Justice Kennedy wrote that “The analysis would be different if town board members directed the public to participate in the prayers….” This is precisely what Judge Cobb does at every meeting when a minister or religious leader gives the invocation prayer.

Local public officials are not allowed by the court’s decision to require those in attendance at such meetings to participate by standing, bowing heads, closing eyes, or saying “amen” at the end of what are usually sectarian prayers foisted by the majority on everyone else. This restriction strikes me as appropriate. If I wanted politicians to tell me how to be religious, I would live in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, or some other officially theocratic country.

Typically, Judge Cobb directs those in the audience to “stand” or “rise” for the invocation. He then introduces the minister or religious leader who has been asked to give the opening prayer, most of whom end with “In Jesus’ name” or “In the name of our Savior,” or something similar. He often thanks the minister for “the prayer.” In many recent meetings, when no minister has been available, the Judge has directed people to stand, has asked for a moment of silence, and has told those in attendance to think about certain topics or people of interest to him.

Competent adults are completely capable of doing their own praying and thinking.

Such paternalism is completely unnecessary. Competent adults are completely capable of doing their own praying and thinking. They don’t need a government official to guide them in the right way or direct them to participate in some Christian or Hindu or other religious practice sponsored by the Commissioners Court. Providing that guidance is the responsibility of religious leaders.

Hays County officials continue to engage in exclusionary invocations, limiting them only to religious officials. Invocations need not be religious events; a non-religious invocation can create the desired solemnity suitable for such an occasion, which is, after all, the purported reason for the prayers approved by the Supreme Court majority.

The history of religion in government decisions

In the Greece decision, the Supreme Court seems to have abandoned for all time the “Lemon Test,” derived from the case named Lemon v. Kurtzman, issued 43 years ago. It provided a bright line to determine whether a legislative act violates the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. To be constitutional, the Court in Lemon concluded,

- The government’s action must have a secular legislative purpose;

- The government’s action must not have the primary effect of either advancing or inhibiting religion;

- The government’s action must not result in an “excessive government entanglement” with religion.

The court decided then that if any of these parts are violated, the government’s action is deemed unconstitutional under the Establishment Clause. Were the “Lemon Test” applied to most invocation prayer practices today, the practices would fail all three parts. But this activist majority has chosen to ignore this long-standing precedent.

The modern efforts by the religious right to “take back” the government for their religious purposes likely have their roots in the 1962 decision in Engel v. Vitale, which struck down a New York state-mandated prayer in public schools as a violation of the Establishment Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

This decision was followed by the 1963 decision in Abington v. Schempp, which prohibited state-mandated Bible reading and instruction in public schools in Pennsylvania, along with its companion case, Murray v. Curlett, which struck down a Baltimore school district rule that promoted either prayer or the recitation of the Lord’s Prayer in public schools. Both decisions were found to violate the Establishment Clause. The Supreme Court made clear in these two cases that the government must remain neutral in matters of religion.

Those decisions adopted an important standard: for a law or government rule to survive the prohibitions of the Establishment Clause, it must have “a secular purpose and a primary effect that neither advances nor inhibits religion.” The “Lemon Test” eight years later grew out of this jurisprudence, much like the 1963 cases built upon the reasoning in Cantwell v. Connecticut, a 1940 free exercise case that struck down a Connecticut law that required Jehovah’s Witnesses to obtain permits before promoting their religion by going door-to-door in New Haven.

Everson v. Board of Education, which overturned a New Jersey policy of using taxpayer money to pay for transportation of children to parochial schools.

Another important religion case was decided in 1947, Everson v. Board of Education, which overturned a New Jersey policy of using taxpayer money to pay for transportation of children to parochial schools. The court explained its decision:

The “establishment of religion” clause of the First Amendment means at least this: Neither a state nor the Federal Government can set up a church. Neither can pass laws which aid one religion, aid all religions or prefer one religion over another. Neither can force nor influence a person to go to or to remain away from church against his will or force him to profess a belief or disbelief in any religion. No person can be punished for entertaining or professing religious beliefs or disbeliefs, for church attendance or non-attendance. No tax in any amount, large or small, can be levied to support any religious activities or institutions, whatever they may be called, or whatever form they may adopt to teach or practice religion. Neither a state nor the Federal Government can, openly or secretly, participate in the affairs of any religious organizations or groups and vice versa. In the words of Jefferson, the clause against establishment of religion by law was intended to erect ‘a wall of separation between Church and State.’ [Emphasis added.]

The next religion case was McCollum v. Board of Education, decided in 1948. In Illinois, religious teachers were employed at the behest of a private religious group that included representatives of Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish faiths, to give religious instruction in public school buildings once each week.

The children of parents who did not want their children to attend the religious instruction were required to go to separate classrooms for secular study. The religious classes were voluntary in name only because the schools put pressure on students to attend, a circumstance the plaintiff, Vashti McCollum, believed was coercive toward her young son.

Justice Black’s majority opinion included a standard that could be applied to government-sponsored prayer:

…the First Amendment rests upon the premise that both religion and government can best work to achieve their lofty aims if each is left free from the other within its respective sphere. Or, as we said in the Everson case, the First Amendment has erected a wall between Church and State which must be kept high and impregnable.

If history and tradition are really valid constitutional standards, none of these religion cases would have been decided against the establishment of religion that they prohibited. Neither Justice Kennedy nor any of his brethren adequately justified adopting such standards in government prayer decisions.

Taking citizen action against the Greece decision

Since there is little chance that church-state jurisprudence related to religious invocations before government bodies is likely to change while the religious-right cabal is in control of the Supreme Court, those of us who want to keep religion out of government will have to get creative. The following suggestions have come to mind or been brought to my attention:

1. Ministers or religious leaders who understand the problems with government-sponsored prayer have several options. When asked to give a government-sponsored prayer, they can politely refuse to participate and explain their reasons. Others may prefer to give an appropriate invocation that is not a prayer. A third option is to actively organize religious people to oppose the fundamentalist evangelical Protestant Christians who are behind most government-sponsored prayer.

2. As long as government prayer continues, those us of in attendance who disapprove can remain seated during the prayers, heads unbowed.

3. Anyone who disagrees with the praying can walk out during the prayer. There is nothing improper in this. The US Supreme Court has even suggested this as a proper response for those who object to the practice, at page 22 of Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion in Greece: “Should nonbelievers choose to exit the room during a prayer they find distasteful, their absence will not stand out as disrespectful or even noteworthy.” Of course, it is obvious how out of touch with the real world these justices are. My experiences in Hays County lead me to believe that any such exit during a prayer will be viewed as highly disrespectful, and is likely to be commented on by public officials and other citizens who disapprove.

3. Anyone who disagrees with the praying can walk out during the prayer. There is nothing improper in this. The US Supreme Court has even suggested this as a proper response for those who object to the practice, at page 22 of Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion in Greece: “Should nonbelievers choose to exit the room during a prayer they find distasteful, their absence will not stand out as disrespectful or even noteworthy.” Of course, it is obvious how out of touch with the real world these justices are. My experiences in Hays County lead me to believe that any such exit during a prayer will be viewed as highly disrespectful, and is likely to be commented on by public officials and other citizens who disapprove.

4. Most city council and commissioners court meetings afford citizens a public comment period. In Central Texas, the time a person may speak on the topic of the person’s choice is frequently three minutes. If enough people complain for three minutes each about government-sponsored prayer and they do so often enough, perhaps the governing body will decide that it’s time to change its religious practice.

5. Since the Supreme Court has foreclosed the courts as an avenue for the redress of this grievance, it may be time to demand of the local public bodies that they include nonreligious invocations along with Christian prayers. After all, both the US Constitution and the Texas Constitution include Equal Protection clauses. It is past time for the nonreligious to be treated equally with Christians and other followers of religion.

6. In the last five years that I have closely followed invocation practices in Central Texas, I have never heard a public official object to audience members joining vocally in the frequent conclusion of “Amen” to Christian prayers. If it is permissible for audience members to indicate their approval of the prayer by saying “Amen” for all to hear at a prayer’s conclusion, those who object to the prayer should be within their rights to say aloud, “No,” or “Nonsense,” or indicate disapproval with some other vocalization.

7. For those of us who come from the civil rights and anti-war tradition of protest and nonviolent civil disobedience, it will seem natural to organize like-minded folk to attend these prayer meetings in great numbers. When we are told to rise for the prayer, twenty or thirty or more people can get up and begin to file out of the room in an orderly fashion, as the Supreme Court said that we should do if we choose to leave during the prayer. Following the direction of the Supreme Court would not even constitute civil disobedience. It would be supremely legal and constitutional.

8. A more time-consuming and less immediate way to deal with public meeting prayers sponsored by home rule cities that have initiative and referendum processes in their charters is to initiate an ordinance prohibiting sectarian invocations or forcing a referendum on the issue. Of course, since the problem is the majority forcing prayers on the minority, referenda may be of no more value in dealing with government prayer than a referendum would have been in the 1950s to secure the civil rights of black people.

I look forward to continuing to fight against the evangelizing of local government by the religious right.

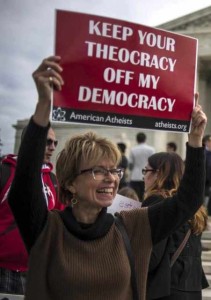

Whatever way fair-minded people choose to oppose government prayer by mostly Protestant Christians, I look forward to continuing to fight against the evangelizing of local government by the religious right now that we know that the courts will no longer keep the theocrats at bay.

The aftermath of the Greece decision

As a friend said to me, the Greece case is a victory for all Christians who need the government to endorse their religion, which shows that they have too much faith in the government and not enough faith in their chosen religion.

Until public officials open up invocations to the nonreligious, to atheists, and to freethinkers, invocations will remain an exercise in promoting religion. The Supreme Court majority favors this result as it moves us closer and closer to the kind of theocracy many of our forebears thought they were escaping when they adopted the Constitution and, later, the Bill of Rights.

In her dissent, Justice Kagan made the problem with the Greece decision crystal clear:

When the citizens of this country approach their government, they do so not as members of one faith or another. And that means that even in a partly legislative body, they should not confront government-sponsored worship that divides them along religious lines.

We have now returned to what author Katherine Stewart has termed a “soft” establishment of religion — “a system in which formal guarantees of religious freedom and the official separation of church and state remain in place, but one religion (Christianity) is informally or implicitly acknowledged as the “approved” religion of the majority….”

Since the courts will not prevent the “soft” establishment of religion, we must oppose it by other means, even if some of those means will not be approved by some public officials and citizens. History is on our side because we remember the Boston Tea Party, the struggle for women’s rights, the civil rights movement, the long conflict over school desegregation, and the battle for the right of the handicapped to be treated equally.

I hope that someday our government will treat all people equally, without regard to their religious beliefs or their moral consciences, because it is the right thing to do, and because equality means dignity for everyone.

Read more articles by Lamar W. Hankins on The Rag Blog.

[Rag Blog columnist Lamar W. Hankins, a former San Marcos, Texas, city attorney, also blogs at Texas Freethought Journal. This article © Texas Freethought Journal, Lamar W. Hankins.]