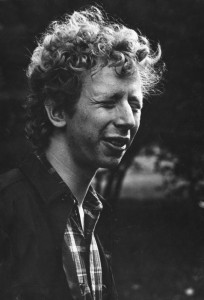

Anti-war activist Howie Machtinger, veteran of SDS and the Weather Underground, believes we should get the facts straight about Vietnam.

Vietnam was near the heart of Howard Machtinger’s life from about 1965, when he was a 19-year-old student, to 1975, when the war ended and weary American troops came home. Vietnam is near the heart of his life once again.

In those days, he belonged to SDS and later to Weatherman and the Weather Underground. These days, he’s a member of Veterans for Peace, the organization that has launched a campaign that demands “Full Disclosure” and “An Honest Commemoration of the American War in Vietnam.”

The Full Disclosure Movement, if one can call it that, also asks for recognition and acknowledgement of the groundbreaking teach-ins that brought the war to the attention of thousand of curious college students across the country. Next year, 2015, marks the 50th anniversary of the first sessions that educated a generation about torture, napalm, the CIA, and more.

Like Howard Machtinger and many others, Tom Hayden remembers them well. “It was the style of the time to be inclusive, not dogmatic,” he said in a recent email.

The name was borrowed from the sit-ins, so it was inspired by the student civil rights movement. The teach-ins helped to expand the movement from the margins to the mainstream. They led to further investigation of university ties to the military and the CIA and served as a participatory model for university reform. And finally, the teach-ins surfaced a constituency broad enough so that the politicians couldn’t ignore the argument and the coming impact on elections. Unfortunately, we have seen no such phenomena in response to, say, the Long War, or Snowden’s revelations.

According to the organization’s website, “the Full Disclosure Campaign represents a clear alternative to the Department of Defense’s current efforts to sanitize and mythologize the Vietnam War and thereby legitimize further unnecessary and destructive wars.”

Machtinger is as impassioned now as he was at 19, and perhaps more clear-headed. “This is an opportunity to introduce a new generation of students to some of the hard won understandings of the antiwar movement and supplement them with ideas and actions appropriate for a new generation,” he says.

Howard Machtinger, left, with Huu Ngoc, Vietnamese author, translator for Ho Chi Minh, and cultural ambassador, Vietnam, 2011. Photo by Anzia Bennett .

Jonah Raskin: In the history books 1968 gets the lion’s share of attention. It was a culminating moment. But 1965 was a big year, too. Would you say how?

Howard Machtinger: It was the year of the major U.S. escalation and the first mass demonstration in Washington, D.C., organized by SDS and the first teach-ins, too.

Where were you in 1965? What were you doing?

I was a junior/senior at Columbia on the periphery of the antiwar movement.

When and where did you first protest against the War?

I’m trying to remember. I was at a campus demonstration in the spring of 1966. Then, I was at the April 15, 196, protest in New York City, later at a sit-in at University of Chicago in the spring of 1967. I was at the Stop the Draft week in Oakland in the fall of 1967 and in NYC again protesting against a meeting of the Foreign Policy Association.

Can you describe briefly the process of your own radicalization in the 1960s?

As a first year student, I worked with Columbia CORE. In the winter of 1965, I heard Malcolm X speak. He said the obvious, but I had never thought of it before — that whites were the minority in the world. Dave Gilbert organized me. Ted Gold brought me to my first SDS convention in the fall of 1967 at Madison. In the spring of 1967 I was “exiled” from the University of Chicago, and traveled widely in the fall of 1967. After the Madison SDS convention, I went to the Bertrand Russell War Crimes Tribunal (about which Sartre later wrote an article entitled “On Genocide” which appeared in Ramparts.) I heard U.S. army personnel describe torture, the use of napalm, and for the first time I heard about Agent Orange. From then on I was deeply committed.

What are your own memories of those first teach-ins?

The foolishness, the condescension, and the ineptitude of the State Department spokesmen who didn’t deal with the issues that were raised.

On the whole, universities failed to educate students about “current events,” as they were called, weren’t they? There weren’t many professors who told the truth about Vietnam, Korea, and the American Empire.

I don’t remember any class that dealt with the war. As a senior at Columbia in 1966, I was in a seminar with Daniel Bell and Steven Marcus on Literature and Society. At the final meeting which was supposed to be a kind of laying-on-of-the hands for future scholars, an angry debate about the war broke out which effectively scuttled the dinner that was scheduled.

How would you describe Columbia University as an institution of learning in the 1960s?

I learned something about how to read and think critically and absorbed the Western canon, particularly in political and sociological theory.

I visited Hanoi in 2005, on the 20th anniversary of the end of the war. I remember Vietnamese men in their seventies talking to me about the Japanese War, the French War, and the American War. The “American War in Vietnam” seems like a more accurate phrase than the “War in Vietnam” doesn’t it?

Yes! Calling it the Vietnam War excludes the actual perpetrator.

When, where and how did you become aware that the U.S. Government was lying to U.S. citizens about the American War in Vietnam?

At the teach-ins.

I remember days at Liberation News Service when all work stopped and everyone watched Walter Cronkite on the CBS evening news. Did you watch him? In hindsight what would you say about his reporting?

I rarely watched him or any TV at the time, though I remember people remarking that they knew the Tet offensive was significant because Walter got up off his ass and pointed at a map and declared the war a stalemate.

What do you think Weatherman and the Weather Underground added to the discussion and debate about Vietnam? What if anything did those organizations say of significance that no one else in the white left was saying?

I have written a lot about this. Rag Blog readers can see an article I wrote entitled, “You Say You Want a Revolution,” that was published in In These Times. I would say here that we got caught up in trying to prove we were as radical as the NLF and the Black Panthers and mistakenly and unnecessarily made armed resistance a dividing issue in the movement when strategically the goal was withdrawal from Vietnam.

You want an “Honest Commemoration of the American War in Vietnam.” For readers of The Rag Blog could you say briefly what that means?

Our nation is being increasingly militarized with hero worship of the military as a key ideological cornerstone. Obama and the Pentagon avoid dealing with the actual horror and injustice of that war. There are two key parts to an honest commemoration: one, remembering the harm of the war (at least two million Vietnamese civilians were killed, millions displaced, Agent Orange sprayed.) Two, we want to honor the resistance to the war in Vietnam, all over the world, and in the U.S. — including importantly by GIs and veterans.

What is the legacy of the American War in Vietnam for you, now in 2014?

What we now call Euro-centrism barely had a name, so ingrained were notions of Western superiority in Western consciousness, so taken for granted. What mattered happened in the U.S., Europe, and the Soviet Union. Everything was reduced to the white centers of action. Open-minded Americans began to make a human connection, to the Vietnamese victims of U.S. bombs, napalm, Agent Orange, and massacres. They moved away from demonization, sometimes recognizing the Vietnamese ability to outmaneuver, outthink, outlast, and outfight a superior technological force. There was an initial sense of the Vietnamese as fellow human beings.

War scene in Bao Trai, Vietnam, 1966. Photo by Horst Faas / AP. Image from Full Disclosure website.

What do you think were the main factors that contributed to the end of the war?

The persistence of Vietnamese resistance. The solidarity of people around the world that isolated the U.S. The growing unwillingness of the military to fight. The domestic opposition that connected to GIs and people around the world.

How significant were the peace and anti-war movements in the U.S.?

They were significant, but it’s hard to isolate one factor from the rest. Domestic resistance stimulated and was stimulated by GI and veteran resistance as well as resistance around the world and by the Vietnamese themselves. I think that the movements that existed then can be used as a precedent for action today and help rebuild the dynamism of the peace and justice movements.

Of all the speakers you heard in the 1960, who would you single out as especially moving?

Malcolm X, Carl Oglesby, Fred Hampton, Diane Nash, Vivian Rothstein.

I remember the march on the Pentagon. Someone had a sign that said, “LBJ Pull Out Now like Your Father Should Have Done.” It got my attention. What slogans or signs do you remember to this day?

“Hey, hey LBJ how many kids did you kill today?” “No Viet Cong ever called me N…” “Stop this senseless killing.” “Power to the people.” “The NLF is gonna win.”

If there’s one thing that you could have done differently in that era what might it have been?

Channel the movement into militant nonviolent action as opposed to random violence. And focus more on what was strategically crucial: getting the U.S. out of Vietnam rather than pseudo-revolutionary acting out.

Were you drafted? How did you avoid going into the military?

I wasn’t drafted, though during the 1968 sit-in at the University of Chicago I received a purported call from my draft board supposedly reclassifying me. I tend to doubt that this was authentic, but never checked it out. Some congressional committee listed me as dangerous so perhaps they didn’t want me.

Can you describe Veterans for Peace, the organization you are working with? Why them?

Veterans, as distinct from much of the antiwar movement, didn’t forget about Vietnam and didn’t move on to other issues. They were indelibly marked by the war. They organized in 1985 and have a membership in the thousands all around the country. Traveling in Vietnam in the last decade I met some wonderful vets. In fact the idea for our Full Disclosure campaign originated with an American veteran who lives in Hanoi.

What’s the word on Hanoi?

It has the buzz of a big city with people in the streets eating, drinking and talking. The traffic is crazy and one has to relearn how to cross a street. There are 4 million motorbikes in Hanoi. The people are friendly; they remember the last time you walked into their shop no matter how many years ago.

Read more articles by Jonah Raskin on The Rag Blog.

[Jonah Raskin is a Rag Blog contributing editor and a Professor Emeritus at Sonoma State University.]

I would like to get in touch with howard machtinger

We share the same name and identical birthday. I live in Toronto canada. My phone number is 416 967 1717.

It would be greatly appreciated if you could make this happen.