Reimagining Detroit:

Urban gardens and green economy

mark seismic cultural shift

By Corey Hill / AlterNet / March 22, 2011

DETROIT — On February 16, Michigan’s Governor Rick Snyder signed into law a sweeping emergency financial management bill, one that will give him wide powers to appoint financial managers across the state.

Cities in financial distress will be assigned emergency managers, who will have the power to suspend collective bargaining, terminate city employees, even dissolve local governments completely — whatever is deemed necessary in the pursuit of a “balanced budget.”

Critics have called it the most undemocratic legislative measure in recent United States history.

The plan, Gov. Snyder claims, is a response to the very real budget problems facing Michigan. Many cities across the state face default. Add to that high unemployment, cities in disrepair, and the collapse of vital industries, and the situation can rightly be deemed an emergency.

Perhaps no city is more emblematic of the challenges facing the state than Detroit. The city has an annual budget deficit of $155 million, and long-term debt totaling $5.7 billion. Fewer than half of its students graduate high school. There are parts of the city where streetlights don’t come on at night and trash goes uncollected.

Detroit is hurting, for sure. All the statistics about lagging graduation rates and economic stagnation can be implied in a single photograph of an empty street, the cinders of an abandoned home that has been burnt to the ground peeking through the snow.

But Detroit has another story, fighting to be noticed against the widespread perception of decay and downturn. It’s a narrative about an urban gardening mecca and a cultural cornerstone, a city where solar panel installation classes also teach demand side economics and relaxation techniques. Look closely at Detroit, and you’ll learn lessons with implications far beyond the asphalt capillaries of the Motor City.

As Detroit social justice activist William Copeland says,

The problems we face in Detroit are being mirrored all around the world: privatization, land grabs, issues of food sovereignty, the struggles for community stability and self-determination.

And the solutions don’t lie in budget cuts or emergency financial managers.

The alternative solution

It is noon at the D-Town Farm in Detroit, and sunlight muscles through the clouds. Used tires double as flowerpots, multichromatic blooms pushing through the giant rubber rings spaced throughout the garden. Volunteers tend the plants as a staff member leads a group of city students on a guided tour, describing the growing habits of the tomatoes and the workings of the brightly painted compost bins. Everywhere are signs of vibrant renewal.

The two-acre farm in Detroit is a project of the Detroit Black Food Security Network, a national leader among the dozens of urban gardening organizations in the city. Use of reclaimed materials, cooperative purchasing, community gardening — principles at work in Detroit’s urban gardens — are found in similar efforts across the country. But Berkeley or Portland this is not. These gardens have different roots.

Ron Williams, founder of Detroit’s alternative weekly Metrotimes, and Dragonfly Media:

What people have to understand is that the urban agriculture, neighborhood economic development and justice work happening in Detroit is not a lifestyle choice, it is dead-on self-determination activity for survival by the residents of this devastated city.

Necessity is a cruel mother, but certainly an efficient one.

The greater Detroit area is the nexus of an entire host of progressive enterprises, notable for both the diversity of its participants and the diversity of its projects: the East Michigan Environmental Action Council, Michigan Welfare Rights Organization, Centro Obrero de Detroit, Global Exchange, South East Michigan Jobs with Justice, the Greening of Detroit, and the Sierra Club.

On the energy front, small-scale solar is taking off in the city, fueled by community learning enterprises that provide valuable education to citizens in solar panel installation and maintenance. Weatherization projects led by community members serve multiple markets, youth participants learning a valuable trade while saving their neighbors money and saving the ozone.

Self-examination is part of the process of growth, too. The Nsoroma Institute on Detroit’s East Side works with young people to promote cultural values, self-identity, and political awareness. The Black Alliance for Just Immigration, a Pan-African organization, looks to convey an African-American perspective on immigration issues.

The Detroit Digital Justice Coalition is working with Detroiters to take back the media. Their core programmatic principles are universal access, participation, common ownership, and healthy communities. They want individuals who have traditionally been excluded from the media to have a voice, tell their own stories, and own the means of transmission.

Divergence

Detroit is in the throes of rebirth, but it’s not a lockstep march toward a glorious future. There are challenges, both internal and external. The single greatest source of opposition facing Detroit’s progressive community may be the city and state government.

Adrienne Brown, co-coordinator of the Food Justice Task Force, says,

The mayor’s instinct to look outside the city for planners and proposals, as opposed to looking to communities, organizers, and community groups for the ideas and solutions the city needs — that’s the main obstacle right now. Instead of being able to just move forward the solutions the city needs, organizers have to split their time trying to stop the mayor from moving forward on proposals which come from people who don’t know and love the city and its people.

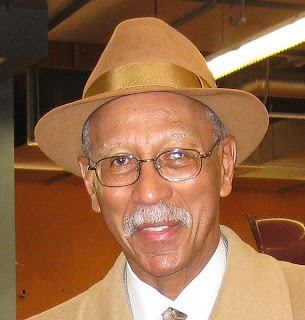

Major David Bing’s recent open call for assistance is a prime example of a willingness to look outside city limits for solutions. In response to Mayor Bing’s call, the city has been flooded with answers — from foundations, outside NGOs, and a glut of city and urban planners, all clamoring to fix Detroit.

A February profile in The Washington Post highlights the mayor sifting through the possibilities, brow furrowed as he mulls the various solutions he has been offered. More art. Closing down neighborhoods. Massive corporate-run urban farms. There are as many proposals to fix Detroit as there are vacant lots collecting Snickers wrappers and Pabst cans.

The interest in making a change is appreciated, but many Detroiters rankle at the mayor’s decision to provide attention and financial support to so many outsiders while valuable community efforts go unnoticed and unused. Why not take the time to listen to the answers from lifelong residents, they ask?

Ford, please come back

Detroit’s streets are unusually wide. This is usually one of the first comments first-time visitors make. The answer to the mystery of Detroit’s roomy streets is an illuminating lesson of the power dynamics at play here.

In the early 1900s, before the automotive manufacturing industry came on the scene, there was in fact a highly efficient, widely used mass transit system in the city. Widely available cheap mass transit does not a car driver make, so once the automobile industry became powerful enough, they bought out the light rail and dissolved it.

Not many people seemed to mind. The American automotive industry generated tens of thousand of jobs for decades, good union jobs that could provide for an entire family. The automotive industry ran the city, and for the most part, people felt they had it good, even without the streetcars.

And people want that feeling back.

The conflict between city government, the progressive community, and the wider citizenry is perhaps most apparent when it comes to manufacturing.

Mayor David Bing is courting businesses with an eye toward rebuilding the manufacturing sector through tax incentives and rebates. For the mayor’s office, any comers will do. The Bing administration has little concern for the types of industry being courted, and many citizens agree. They want jobs, and they don’t care much what they’re building. It could be cars, it could be cruise missiles.

Or it could be wind turbines. The alternative proposal is to put the region’s skilled labor force to work building the next generation of green technology, turning Detroit into the green manufacturing hub for North America.

Factories that once made Fords and Chevrolets could now make solar panels, electric streetcars, and electric cars. Detroit could once again become the heart of America’s industrial engine, albeit one that pumps significantly greener lifeblood.

City officials are not opposed to green manufacturing. In fact, the mayor has already proposed using federal money in support of a light rail project. But for Detroit to become a green manufacturing center, the effort would require significant subsidies, rebates, and investment incentives.

For some, it’s not enough to change the output. They’re calling for a revolution in the production model, as well.

Detroit has long been a city with a traditional economic model — worker, employer, work in, paycheck out, with orders coming straight down from the top. This hierarchical model has been dominant since the advent of industrial capitalism.

Frank Joyce, former communications director for United Auto Workers, says,

For some people, they want to go back. Even though they’ve seen all this, they want to say “Okay, how do we put Humpty-Dumpty back together again?” Even if we could go back, can’t we do better anyway? Detroit offers the opportunity to reimagine — reimagine a city, reimagine work.

Reimagining work, by adopting models like the Mondragon Corporation in Spain — a confederation of cooperatives from the retail, industry, finance, and knowledge business sectors. Though the model has yet to be applied on a wide scale to heavy manufacture, urban gardening, artists cooperatives, and light manufacture co-ops have flourished in Detroit.

Green manufacturing, in whatever form it eventually takes, will almost certainly provide an economic boon to Detroit. As resources grow scarcer and eco-consciousness blooms, the market potential for green goods, including heavy manufacturing, shoots upward. But the degree to which it will revitalize the city — that’s a matter for debate.

Critics contend that even a completely revitalized manufacturing sector would not bring things back to the way they were. Thanks to automation, factories use fewer workers. What once required 5,000 people now only requires 500. Even with an industrial output equivalent to the city’s peak, the manufacturing sector would employ far fewer than it once did.

The situation is further complicated by the reticence of some citizens to engage with other sectors of the growing alternative economy in hopes that salvation might someday come in another form. Why waste your time with”bean patches” (as Jesse Jackson referred to urban gardens) when manufacturing jobs might be just around the corner?

[R]evolution

Detroit’s struggle matters.

As the Great Recession drags on and city and state governments across the country propose sweeping budget cuts and various draconian measures, Detroit’s community-led efforts for change offer a vision for a saner alternative.

To those who would propose gutting schools and privatization, more of the same ruinous policies that have created so much devastation, the counterargument is sprouting from abandoned lots in Highland Park, it’s collecting sunlight on rooftops in the East Side.

Detroit matters because the contrasts are so clear, the opportunity for reimagining is greatest where the collapse of the so-called American Dream has resulted in such extremes.

Frank Joyce says,

Here in Detroit you see these shirts, they say revolution, but the R is in brackets — [R]revolution. Revolution is evolution. And evolution is revolution.

The essence of Detroit’s story is one of growth by necessity, incremental grasping toward a seismic shift in culture, environmental policy, and economics. The efforts of Detroit’s changemakers have been guided primarily by trial and error — a willingness to step outside the bounds, to fail, and try again. The lesson is simple: change requires a concerted effort, but it doesn’t require a road map.

William Copeland says,

I honestly feel that the work being done in Detroit is setting the stage for a 21st-century tangible socialism, not rooted in the left or in the theoretical critiques of capitalism but from concrete struggles for the necessities of life and engagement with the institutions that have failed tens of thousands in Detroit.

Detroit’s struggle matters, because there isn’t a tidy conclusion. Nothing is certain. There are gaping budget deficits and light rail projects, abandoned lots and beautiful gardens. There are emergency financial managers, and there are community teachers.

And there are Detroiters, hard at work on a revolution in progress.

[Corey Hill is a human rights activist, community arts supporter, and writer who lives in San Francisco, Calif. This article was originally published at and was distributed by AlterNet.]

Michigan has had serious financial problems since around the time Jesus wore diapers. The state never completely recovered from the deep recession of the 1950s. No one I know of knows why. That would take an in-depth study of Michigan's political history going back to the great depression. A study that would take years. Does anyone really care that much? Why don't we just sell Michigan to