Donald Cox, 1936-2011:

The beauty of the moon

and the passion of the Black Panthers

By Jonah Raskin / The Rag Blog / March 15, 2011

It was sad news that former Black Panther, Don Cox, died in France, February 19, 2011, at the age of 74, but I had to laugh at The New York Times obituary by Bruce Weber that described the Panthers as “the socialist movement founded by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale in Oakland, Calif., in 1966.” True, the Panthers were founded by Newton and Seale in 1966 in Oakland, but they were not a socialist movement, not by any stretch of the imagination.

They did for a time provide breakfast for children and they did want community control of institutions, such as police departments and schools, in black neighborhoods, but they did not advocate socialism.

They were part of the Black Nationalist movement that made allies with young, radical whites, and they also shared optimism and the political tactics of the anti-colonial upsurges that spread across the Third World in the 1960s.

I met Donald Cox — “DC” as we called him — and got to know him, briefly, in Algiers in 1970. I had gone to Algiers with a group of Yippies to meet Eldridge Cleaver and Timothy Leary, both of whom were wanted by U.S. authorities and were living in exile.

DC was the mellowest. DC was the coolest, and much less of a megalomaniac or egomaniac than Cleaver or Leary. In fact, he wasn’t a megalomaniac or an egomaniac at all. He didn’t want to change the world with guns or LSD and he didn’t want to run it either. Like Cleaver and Leary, he was also wanted by the FBI and considered “dangerous,” but he seemed wistful to me.

In Algiers, he was concerned about the security of the Panthers and their Embassy because CIA agents monitored their activities. He was also a gracious host who took us — Stew Albert, Anita Hoffman, Brian Flanagan, Jennifer Dohrn, Marty Kenner and me — on a tour of the city, pointing out historical landmarks. He brought us one afternoon to the Place du Martyrs and explained that the French had executed suspected Algerian guerrillas here and then dumped their bodies into the harbor.

He turned to Jennifer Dohrn and asked her, “What color is that water?” She looked down. I looked down. We all did. “It’s reddish-blue,” Jennifer said. And indeed it was. It looked like the sea was awash in blood. “The Algerians say that it’s their blood that gives it that color,” DC explained. “The red blood of the guerrillas changed the color of the Mediterranean.”

At a feast at a seafood restaurant, DC was our official host and sat at the opposite head of the table from Cleaver. He ordered food for everyone — shrimp and fish and white wine. DC was also made uneasy by two African Americans at the bar who said they were from San Francisco, and whom he suspected worked for the CIA. Sekou, one of the Panthers, spoke softly.

“I got us all covered,” he said. And indeed he did. I looked under the table and saw that he had a gun in his hand. I was confident he’d use it if need be. He had hijacked an airplane at gunpoint to get to Algiers.

DC didn’t have a gun in Algiers. I never saw him with one, either under a table or on his own person, though I did see Cleaver with an AK-47 in his lap. In 1970, DC expressed concern about living in exile. He hoped that he would not have to remain for the rest of his life outside his own native country. He missed San Francisco.

He did live in exile for the next 40 years of his life; his widow noted that before his death, exile had begun to wear on him. I’m sure it did and yet what strikes me most about DC now is his longevity. He lived longer than many of the Black Panthers, such as Huey Newton, and Eldridge Cleaver, who became a born-again Christian, a Republican, and a crack-head in the 1990s in Oakland.

DC never turned his back on his ideals, his passion for justice or his appreciation of beauty.

One night, we all looked up at the moon and admired its beauty.

“In Babylon, you can’t appreciate the moon’s beauty,” DC told us. “But here you have the time and space to dig on it.” That’s the way I’d like to remember DC, the Black Panther Field Marshal, who lived more than half his life in exile, and who learned in exile to appreciate the beauty of the moon.

[Jonah Raskin teaches at Sonoma State University and is the author of For the Hell of It: The Life and Times of Abbie Hoffman.]

With regard to whether or not the BPP advocated for socialism in the 1960s and early 1970s, in his introduction to the 1970 book that he edited, “Black Panthers Speak”, U.S. labor historian Philip Foner wrote that “one should add that the Black Panthers, while by no means the first blacks in the United States to oppose the capitalist system and espouse the cause of Socialism, were the first to do so as a separate organization…The Black Panthers, though favoring Socialism and coalitions with other oppressed groups, retain their separate identity as a revolutionary movement…”

And in February 1970, the Black Panther Party’s national office also issued a statement to the U.S. “Guardian” radical newspaper which stated:

“The Black Panther Party stands for revolutionary solidarity with all people fighting against the forces of imperialism, capitalism, racism and fascism…

“In the words of the party’s chairman, Bobby Seale, we will not fight capitalism with black capitalism; we will not fight imperialism with black imperialism; we will not fight racism with black racism. Rather we will take our stand against these evils with a solidarity derived from a proletarian internationalism born of socialist idealism…”

Marx taught that control of the “means of production” was the path to power, i.e. socialism on the way to what Engels called the “withering away of the state.”

Since the means of production were virtually absent in the black communities, the Panthers, and particularly DC, espoused control of the institutions of society, the means of “serving the people” with defense (police powers), access to food and shelter (welfare and community food centers), and the voice of information (the people’s media).

Home-grown, locally-controlled and self-defended may equal “socialism” in the streets, and solidarity with the international movements for freedom, justice and equality, but there was nothing academic about the pragmatism of the Field Marshall and his friends.

In a 1969 speech before his murder by Chicago police and the FBI, the local BPP leader Fred Hampton said, “We say you don’t fight capitalism with no black capitalism; you fight capitalism with socialism.” I don’t know why Jomo doesn’t think the BPP advocated socialism rather than simply black nationalism. Indeed, that is what distinguished them from other black power organizations of the period.

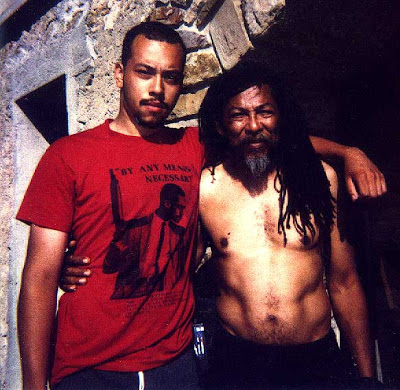

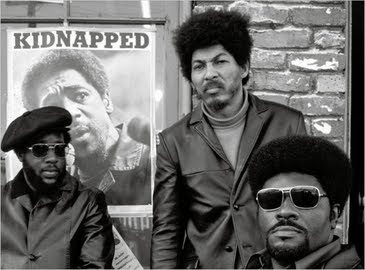

In addition to erring on whether or not the Panthers considered themselves socialist, Raskin also has the identities in the photo of the three Panthers reversed (unless the blog did that by acident). That’s DC in the middle but Big Man is on the right, June Hilliard on the left.

And DC may not have waved his gun around as the other two did, but perhaps that speaks more to his seriousness and shows the others were more interested in grandstanding…