The blue afterwards:

Mourning for Marilyn

By Felix Shafer / The Rag Blog / January 13, 2011

First of three parts

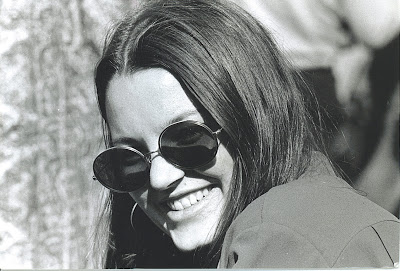

[On December 13, Marilyn Buck, U.S. anti-imperialist political prisoner, acclaimed poet, former Austinite, and former original Ragstaffer, would have been 63 years of age. Scheduled for parole last August after nearly 30 years in federal prisons, Marilyn planned to live and work in New York. She looked forward to trying her hand at photography again, taking salsa lessons, and simply being able to walk in the park and visit freely with friends.

Instead, after 20 days of freedom, Marilyn died of a virulent cancer.

Her death was a great blow to her friends and supporters, to fellow poets around the world, and to the many women she mentored while a prisoner, teaching literacy, solidarity, and survival skills without condescension or pride. In Oakland and New York and Dallas, hundreds gathered to mourn her and to celebrate her life. As a poet of oppression, as a friend, and in fortitude and selflessness, she had no peer.

Yet the acts of violence for which she was sent to prison cloud Marilyn Buck’s revolutionary legacy. Was she a mixed-up kid who had good intentions but fell in with the wrong crowd? Was she a cold-blooded terrorist? Will she be remembered only for her remarkable empathy with the oppressed? Or will she come to be seen as a revolutionary icon worthy of respect for her mind as well as her heart?

Here, a long-time friend and artistic collaborator sets out to mourn Marilyn in a manner appropriate to her life, placing her in the context of her times and showing how she rose above the crowd.

This is the first of three parts.

— Mariann G. Wizard / The Rag Blog]

You’ve gone past us now.

beloved comrade:

north american revolutionary

and political prisoner

My sister and friend of these 40 years,

it’s over

Marilyn Buck gone

through the wire

out into the last whirlwind.

With time’s increasing distance from her moment of death on the afternoon of August 3, 2010, at home in Brooklyn, New York, the more that I have felt impelled to write a cohesive essay about Marilyn, the less possible such a project has become. She died at 62 years of age, surrounded by people who loved and still love her truly. She died just 20 days after being released from Carswell federal prison in Texas. Marilyn lived nearly 30 years behind bars. It was the determined effort of Soffiyah Elijah, her attorney and close friend of more than a quarter century that got her out of that prison system at all.

Her loss leaves a wound that insists she must be more than a memory and still so much more than a name circulating in the bluest afterwards. If writing is one way of holding on to Marilyn, it also ramifies a crazed loneliness. Shadows lie down in unsayable places. I’m a minor player in the story who wants to be scribbling side by side with her in a cafe or perched together overlooking the Hudson from a side road along the Palisades.

This work of mourning is fragmentary, impossible, subjective, politically unofficial, lovingly biased, flush with anxieties over (mis)representation, hopefully evocative of some of the “multitude” of Marilyns contained within her soul, strange and curiously punctuated by shifts into reverie and poetic time.

It’s my hope that others, who also take her life and death personally, will publish rivers of articles, reminiscences, essays, tributes, poems, in print and online. May the painters paint, the ceramicists shape clay, and the doers do works and with her spirit!

Will someone come to write a book-length biography, one capable of fairly transmitting Marilyn Buck’s many sided significance: her character, political commitments, creative accomplishment, and all-too-human failings, to people who never knew about her life? Is such a work possible about someone who lived nearly 30 years behind bars?

Shift: From the back pews of reverie a tinny reel-to-reel replays my voice in 1975 chanting the words of the legendary early 20th century labor organizer and member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), Joe Hill: “Don’t mourn, Organize!” But right now, across the cemetery of dogmas, I have neither strength nor militant nostalgia for any such renunciation of mourning. Others may, but I cannot exhort myself or anyone else to refuse the dolorous walk.

Her precise twang shreds the air: cautioning against overindulgence, saying, Felix, brother, you better chill. I know you’re sentimental just don’t you dare go too far. It’s true. I’m from schmaltzy Brooklyn and she’s straight out of the lanky plains of west Texas. (As her friends say: “the Buck started here.”)

Parts of this piece are written with a 1960s-1970s vocab and it’s more my own writerly failing than anything else, because for sure she’s not a relic of the bygone at all. If I write that she was amazing would it be better to say awesome?

Marilyn was a writer, a dialectical materialist, a freedom fighter, yoga teacher and Buddhist meditator, who did not suffer fools gladly. She was modest and graceful. Behind the wall she was a teacher and a mentor to young women new to being locked up. Decade after decade in the drab visiting rooms of MCC-NY, DC Jail, Marianna Florida, Dublin-Pleasanton California, dressed first in her own clothes — then later in mandatory uniform khaki — she emanated dignified Marilynness: that unforgettable, natural style.

Nowadays, when things go inexplicably lost in the house or pictures fall from the walls of her studio my partner Miranda (who was Marilyn’s commune roommate in 1969-1970) says… oh that’s Marbu moving stuff around again… One night in late September, I dreamed that a note was slipped under our front door. It read:

Dear anguish, you know an end is not the end it’s never only an end at all

When I woke up I wrote: Keywords: woman, sister, freedom lover, contra racismo y sexismo, yogi, theorist from internal exile, poet, collective worker, student, madrina, artist, reader/writer, comrade-compañera, john brown, antigone, she who cuts through revolutionary enemy of the state

Accounts of mourning sometimes cross over or, more accurately because mourning is a resistant and achingly tender verb, create a transient bridge from the bereaved privacy of the self — to some sense of shared community. Some will, accurately, point out that this human connection is always a bridge-too-far but even so, gaps and all, it’s what we have.

While she was alive and even more humbly now, I find myself in far reaching debt to Marilyn Buck and hope through the process of writing to move closer to what this relation means and might aspire to. Debt implies relationship. In ancient times, the symbol of suspended balance scales signified a weighing of life/death, good/evil and justice/injustice, not money-debt. It’s no accident that in western myth and culture these scales are balanced by the figure of a woman — often blindfolded to signify impartiality and holding a sword, which represents the power to enforce justice (re-balance).

In her fascinating 2008 non-fiction book, Payback (Debt and the Shadow Side of Wealth) Margaret Atwood clarifies that in ancient Egyptian Africa a miniature of the goddess Ma’at (or her feather — representing justice and truth) was used on the cosmic scale to weigh good and evil in the heart of one who has died. The heart needed to be as light as a feather for the soul to be granted eternal life.

Atwood goes on to say that, along with justice and truth, Ma’at meant balance, the proper comportment towards others, and moral standards of behavior. I don’t know if Marilyn ever read about Ma’at, but she tried her best to embody these principles in steady resistance to our death-driven culture, which equates human value with money.

In our culture, psychologically “normal” citizens are produced to be consumers in the market. That’s the bottom line for this dang shabang. Wrap around, cradle-to-the grave conditioning (branding) creates a default position for the self that our worth=money. People are left fearful, commodified, and habitually driven: hating the never-ending lack (of money, power, status, looks, products, sex) in themselves and envying one another.

Marxists refer to this as commodity fetishism. The tragic human dimension of vulnerability, loss, failing, mortality, and mourning, which is also at the core of our being, is manically denied.

Remember how after the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, the government exhorted everyone to go out shopping to show that our society was unbowed? Then we were taken into a seemingly endless series of wars. Without the humility of mourning there is no learning from experience. Along with the three interlocking oppressions more traditionally named by the left — race, class, and gender — envy and the avoidance of mourning constitute a base from which evil acts and fascist movements spring.

Marilyn worked to renounce this deathly dynamic and sustained, in her everyday life, a radical ethic of gratitude, care, and equality among people. She studied history/herstory and understood that human rights must be fought for and defended if they are to exist at all. There was nothing bogus about her.

I do not believe that I’m alone, among the many, many people who visited and whom she befriended after she was captured, in this feeling of a political and personal obligation to, or better to say: with Marilyn.

Those of us fortunate enough to have known her before she became “notorious” and “iconic” — representations that never sat well with her and which being in Marilyn’s presence were easily dispelled — remember how serious, determined, outspoken, beautiful, and far from perfect she was. It’s no secret that she made political mistakes along the way. The collective political-resistance project she was part of was defeated. Its members paid and some are still paying a very high price.

She came of age in the red-hot crucible of the 1960s and ’70s when large movements from every corner of the earth were on the upsurge, challenging capitalist-imperialism with demands for revolution. It was an era of overturnings and extremes. Marilyn grew up in Texas — where racist and sexist dominator culture combined the toxic violence of america’s segregated south and cowboy west. She witnessed racism everyday and, by high school and college, grew determined to do something to help bring an end to war and white supremacy.

keywords: Mercurial time, oh old space Capsule: Go ahead crack the kernel’s hard discontinuous shell; revisit our more innocent and less destitute history with this bite-sized Almanac backgrounder:

When Marilyn left home to find her way into the popular movement(s), Dylan was singing The Times They Are A Changin’ & Masters of War, the SNCC Freedom Singers, Motown, R&B galore and Nina Simone’s thunderous Mississippi Goddamn! got people up and moving.

It was the overflowing era of Vietnam, Black, Brown, Native American, and Asian people’s power movements, the war of the cities: Watts, Detroit, Newark, and hundreds of urban rebellions brought the fire this time.

Draft cards were torched and many G.I.’s revolted against the war. Feminism and Gay Liberation insisted that the personal-is-political. Student and youth cultural revolt(s) on a worldwide scale (including, although quite uniquely, the massive Chinese cultural revolution) had not yet been pacified and co-opted by the market.

National liberation movements in Southern Africa were bringing an end to direct, foreign, and settler-colonial domination of their countries. The Palestinian people began asserting their national rights. Revolutionary organizations and guerrilla movements, partly inspired by the Cuban example, were organizing above and below ground to strike against “imperialismo yanqui” in Latin America. Radicals spoke of creating “2,3 many Vietnams” against empire.

Inside the United States, the vital foundation of all radical cultural and political developments was the civil rights and Black Liberation struggle. Black people sang, “I aint scared of your jail ’cause I want my freedom!” This movement’s organizing cries of Black Is Beautiful and Black Power! actually inspired people all over the world to throw off internalized oppression and fight the power.

Marilyn joined SDS (Students for a Democratic Society — the country’s largest student organization), worked with The Rag in Austin, and then helped edit the SDS newspaper New Left Notes in Chicago. She stood up against sexism in the organization.

Moving to the Bay Area in late 1968, Marilyn joined in building the San Francisco Newsreel collective, which, like its counterpart in New York, made and distributed radical film documentaries about contemporary struggles. Some influential S.F. Newsreel films taught people about the Black Panther Party; the San Francisco State student strike (led by a coalition of Third World organizations, this was the longest student strike in U.S. history); the Richmond California oil refinery worker’s strike (“On Strike“); the Mission High School Rebellion; and many others. These films, used by organizers spreading news across the country, were an important part of an alternative press movement made up of hundreds of underground newspapers, radio, and press services.

In western Europe and the USA, especially, white people in motion mainly expressed a middle class idealism, rage, and utopian aspiration. Some younger white folks were learning that struggling in alliance with Third World peoples at home and abroad could actually help end the genocidal war in Vietnam, and advance civil and human rights. A new left was born.

For many radical activists, leadership flowed — not from the Democratic Party — but from movements of color and figures like Dr. King, Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, Fannie Lou Hamer, Cesar Chavez. Importantly, we worked with and looked to grassroots leaders of color — in our schools, workplaces, and communities — for direction.

We challenged our personal racism and the social system of white supremacy. Consciousness raising and women’s liberation broke through to identify and challenge patriarchy. By the later 1960s, lesbian and gay liberation was gathering force.

This was a cultural revolution(s) involving radically new, alternative sources of authority and legitimation which threatened the (mostly white, male, straight) powers that be. The rejection of 1950’s Jim Crow apartheid/segregation and northern white suburbia, begun by the civil rights movement in the South, communist resisters to McCarthyism, early 2nd-wave feminism, and artists from the beat/hip/hippie generation(s) ignited a mix and mojo that many people, including yours truly, embraced.

You might say, without falling for romantic nostalgia, that a historical crack opened up and it seemed just possible to break through the myopia, prejudice, and privilege of empire into a better world. Or put it another way we, and this was by no means limited or merely conditioned by the exuberance of youth, had the experience of being deeply engaged with living history.

Even as society was fast becoming more of a spectacle, during this brief pre-postmodern, pre-internet era, we knew that we wanted to be more than spectators. It was as if sleepwalkers in death’s hollow empire were suddenly waking up.

In the advanced capitalist areas of Europe, Japan, and the U.S. anti-empire activity led some small yet significant sectors of the new lefts to move towards increased clandestine militancy, including bombings and armed actions against their repressive governments.*

Inside the U.S. solidarity with Black, Puerto Rican, Native American, Chicano/ Mexicano as well as international liberation movements, were a powerful motivating force for Marilyn and others.

The spirit of this global, historical moment is revealed by Karma Nabulsi, a Palestinian, writing about being a young revolutionary in the 1960s and 70s working to free his country:

The experience of revolutionary life is difficult to describe. It is as much metaphysical as imaginative, combining urgency, purposefulness, seriousness and hard work, with a near celebratory sense of adventure and overriding optimism — a sort of carnival atmosphere of citizens’ rule. Key to its success is that this heightened state is consciously and collectively maintained by tens of thousands of people at the same time. If you get tired for a few hours or days, you know others are holding the ring. (2)

keywords: the hammer this time

Within the Unites States, all movements, organizations, and individuals ranging from Dr. King to Malcolm X, from artists Nina Simone to John Lennon, were targeted because they inspired people to organize for real change. Under the rubric of FBI-COINTELPRO (short for Counter-Intelligence Program) a vast campaign of ruthless and unconstitutional counter-insurgency against the people was sanctioned by both Democratic and Republican Whitehouses.

Far from a “rogue” program led by a “racist and demented” J. Edgar Hoover, what we call COINTELPRO grew to involve the coordination of Pentagon, CIA, local and state police, as well as the FBI. Its mandate was destroy/neutralize radical leaders, organizations and grass roots people through assassinations, fratricidal murders, frame-ups, psychological warfare and forced exile.(3)

Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., Fred Hampton, scores of Panthers and American Indian Movement members were assassinated, as were some key members of the Chicano/Mexicano and Puerto Rican movements. Several Black Panther members were tortured so badly in New Orleans — in a manner consistent with current government torture practices — that trial courts threw out cases against them.

The federal government unleashed a wave of high profile conspiracy trials, most of which, after sowing fear and draining resources, ended in acquittals. Nasty blackmails and bribery were used to recruit informers. This low intensity warfare, along with inner city drug plagues, wars on drugs leading to criminalization of black and brown youth, concessionary pacification (i.e., temporary poverty programs) and the end of the Vietnam war, succeeded in halting much of our forward motion. We were young idealists and we didn’t see this coming.

Vastly expanded federal and state prison systems became the leading form of long-term social control over people of color. Today, with at least 2 million people warehoused under criminal justice control, the U.S. has the world’s highest incarceration rate. One result of the hidden, domestic war is that there are over 100 political prisoners, essentially COINTELPRO captives of the FBI, courts, and prisons, who have remained locked up for the past 25-40 years. They are some of the longest held political prisoners on earth.(4)

There are also people in permanent foreign exile, one of whom died recently at 63 years of age in Zambia. Michael Cetewayo Tabor was a former Black Panther leader in New York, a member of the Panther 21 conspiracy case (of which all were acquitted) and author of the incisive pamphlet: “Capitalism Plus Dope Equals Genocide.” While countries the world over have released their political prisoners from the 1960s and ’70s, some through amnesty and others paroled after serving long sentences, the U.S. still refuses to do so.

All this was a long time ago, but I believe that in many telling ways, when applied to empire and resistance, what the writer, William Faulkner, said in another context is true:

The past is not dead. In fact, it isn’t even past.

In the introductory essay to her translation of Christina Peri Rossi’s poetry book, State of Exile (5), Marilyn writes of the trauma of imprisonment as an exile:

Exile may also be collective, as in the case of the Palestinian people, forced from their homeland, or the people of Darfur, murdered and driven from their lands. And there is another form of exile as well — internal exile — in which one is taken from the location of one’s home and life and is transported to some other outlying, isolated region of their own country. We think of the gulags of the former Soviet Union, for example, or stories from centuries past, but the fact is that internal exile exists here and now, in the United States a country of exiles, refugees and survivors. Prison is a state of exile.

…I a political militant did not choose external exile in time and was captured. I became a U.S. political prisoner and was sentenced to internal exile, where I remain after more than twenty years.

More to come

[Felix Shafer became an anti-imperialist/human rights activist while in high school during the late 1960’s and has worked around prisons and political prisoners for over 30 years. He is a psychotherapist in San Francisco and can be reached at felixir999@gmail.com.]

- Read earlier articles about Marilyn Buck on The Rag Blog.

Footnotes:

(1)This is a very incomplete and utterly heterogeneous list. UK: The Angry Brigade; France: Accion Directe; West Germany: Red Army Faction & Revolutionary Cells; Italy: Red Brigade & Prima Linea. Japan: United Red Army; The IRA in Ireland and the Basque ETA in Spain (both larger and with more support) grew out of centuries long colonization. Within the U.S. some of the revolutionary armed organizations were: Black Liberation Army, Fuerzas Armadas de Liberacion Nacional & EPB-Macheteros(Puerto Rico), Weather Underground, Symbionese Liberation Army, New World Liberation Front, George Jackson Brigade, Red Guerrilla Resistance and United Freedom Front. To my knowledge, there has been no serious historical study of this global phenomenon

(2)London Review of Books, Vol. 32, No. 20 21 October 2010

(3)See the books: Agents of Repression & The Cointelpro Papers, by Ward Churchill and Jim Vander Wall. The Reports of the U.S. Senate Hearings (The Church Committee) 1975, U.S. Government Printing Office. And, the new film, Cointelpro 101 available from www.freedomarchives.org.

(4)The Jericho Amnesty Campaign has been involved in efforts to win amnesty for many years. A campaign is underway to win the release of N.Y. State political prisoners.

(5)City Light Books Pocket Poets Series Number 58, San Francisco, 2008.

I have had the privilege of reading this essay in its entirety, and urge Rag Blog readers not to miss succeeding parts.

This is an important initial evaluation of the life of someone whose significance continues to grow after her death. Whether or not the reader knew Marilyn personally, there is much of interest here.

Many thanks to Felix for the love and respect that infuse this tribute; many thanks to Thorne for a caring presentation.