The psychedelic revolutionaries…

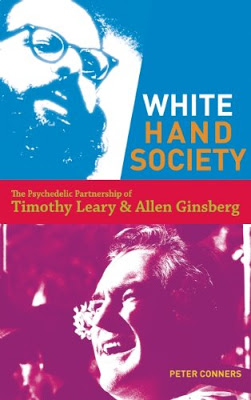

‘White Hand Society:

The Psychedelic Partnership of Timothy Leary & Allen Ginsberg’

By Jonah Raskin / The Rag Blog / October 12, 2010

[White Hand Society: The Psychedelic Partnership of Timothy Leary & Allen Ginsberg, by Peter Conners (City Lights, 2010); Paperback, 200 pp.; $16.95.]

I took LSD for the first time in 1970, and haven’t taken it since then. Three of the trips were with fugitives in the Weather Underground all of them wanted by the FBI. At that time, the clandestine organization of former members of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) insisted that taking LSD was consistent with armed revolution.

To make their point, they took a break from planting bombs to help Timothy Leary, the apostle of LSD, make his escape from prison and to leave the United States for Algeria under a fake passport. It was in Algiers in 1970 that I met Leary, and took LSD with him. I actually enjoyed that acid trip, unlike the previous psychedelic experiences with the Weather Underground. Leary was irrepressible and dangerous — an imp and a mad man.

My experiences in Algiers from 40 years ago came back to me recently while reading Peter Conners’ new book White Hand Society: The Psychedelic Partnership of Timothy Leary & Allen Ginsberg. Conners is a poet, a fiction writer, a book editor, and the author of a memoir, Growing Up Dead: The Hallucinated Confessions of a Teenage Deadhead.

In White Hand Society, he’s an historian and a group biographer. The individuals in the group that he profiles include not only Ginsberg, Leary, and the Weather Underground fugitives, but also many of the figures of the drug and countercultures of the 1960s, such as Ken Kesey, Neal Cassady, Ram Dass, Andrew Weil, and more. Jack Kerouac makes a brief and vivid appearance; his comments about his experiments with psychedelic drugs are well worth reading and pondering.

Conners’ main objective is to trace the connections between Ginsberg and Leary, and to show the impact they had on an era in which taking psychedelic drugs was an integral part of the rebellion and the protests of a generation. Indeed, drugs went hand in hand with the cultural revolutions of the 1960s; they were depicted as a kind of deprogramming of the institutional brainwashing that was carried out by the media and the educational system during the cold war. Moreover, drugs seemed to provide immediate gratification of pleasure.

White Hand Society is largely anecdotal, and the anecdotes, though they have mostly been told before, are well told in these pages. “White Hand Society” is the name that Leary gave to a group of his friends and associates — and just one of a series of names he coined to create a sense of élan and mystery about himself and those around him.

Leary, Ginsberg and their associates come to life in this book, and so do the times they helped to shape. The story moves from Massachusetts to New York to California and to Europe. The sections of the book about Leary are the most vivid and the most trenchant.

Conners doesn’t advance a theory to explain Leary’s behavior or the drug culture, but he does offer a long and illuminating passage from Alternating Currents, a 1967 book by Octavio Paz, the Mexican author and Nobel-prize winner famous for Labyrinth of Solitude. It is well worth repeating here. In the absence of a theory about drugs and addiction it will do nicely.

“We are now in a position to understand the real reason for the condemnation of hallucinogens and why their use is punished,” Paz wrote. “The authorities do not behave as though they were trying to stamp out a harmful vice, but behave as though they were stamping out dissidence. Since this is a form of dissidence that is becoming more widespread, the prohibition takes on the proportion of a campaign against a spiritual contagion, against an opinion. What authorities are displaying is ideological zeal. They are punishing a heresy, not a crime.”

Paz’s comments make a lot of sense. They seem both timely and contemporary, though they were written before the War on Drugs, at least in its modern phrase, began in 1970 under President Richard Nixon. Indeed, Nixon and his drug warriors — and all the drug warriors under every single American president since Nixon — have combated illicit drugs, from LSD to marijuana and cocaine, as though they were zealots on a religious crusade. This year, on the 40th anniversary of the war on drugs, it is perhaps more obviously than ever before a campaign against a “heresy, not a crime.”

Conners does not focus on the drug warriors themselves, but on their victims — on men like Leary who were arrested and jailed for smuggling and smoking marijuana — and on men like Ginsberg who rushed to their defense and who called for the legalization of marijuana.

Conners does not idealize Leary. He depicts him as a showman, a self-promoter, a huckster, and a sham who also became a snitch and cooperated with the FBI in exchange for leniency and for placement in the federal witness protection program

Conners offers a quotation from Leary himself in which he defends his honor and his reputation. “I did not testify against friends,” he told a reporter for The Berkeley Barb, one of the first of the underground newspapers of the 1960s. Leary went on to say, “I didn’t testify in any manner that would lead to indictments against the Weatherpeople… The fact is that nobody has been arrested because of me, and nobody ever will be.”

Conners offers his own interpretation of that statement. “In true Leary mode, he was refashioning the whole boondoggle of busts, imprisonment, federal cooperation… as if it had been nothing more than a game,” he writes. “In Leary’s mind, he had simply worked the system.”

Of course, the fact that Leary was a con artist, a liar, and a victim of his own delusions doesn’t let the drug warriors off the hook. Indeed, the drug warriors and law enforcement officers persecuted and prosecuted Leary again and again on charges of violating the marijuana laws — until they succeeded in sending him to prison. They did the same to hundreds of thousands of marijuana smokers year after year since 1970. In fact, there have been, in the past 40 years, more than 20,000,000 arrests for marijuana — most of them for possession.

That Leary was arrested on marijuana charges for the first time in Laredo, Texas was ironical indeed. After all, Ginsberg had written in his epic poem “Howl” (1956) about the “angleheaded hipsters” who were “busted in their pubic beards returning through Laredo with a belt of marijuana for New York.”

It was perhaps inevitable that their paths — the path of the poet and path of the man who called himself the “high priest” — would cross. Maybe, too, Ginsberg and “Howl” gave birth to Timothy Leary as they helped to give birth to the counterculture of the 1960s. Ginsberg certainly showed compassion for Leary, even after he snitched on friends.

Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin were unforgiving. “Timothy Leary is a name worse than Benedict Arnold,” Abbie said, and Jerry Rubin added, “I know from personal experience with him over the past 10 years that he never had a firm grasp of where truth ended and fantasy began.”

[Jonah Raskin is the author of American Scream: Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” and the Making of the Beat Generation and is a professor at Sonoma State University.]

The last name of the author of the book is Conners, not Conner, as in the text, nor Connors, as in the heading.

Thanks, Diana. It’s corrected. It’s my bad because I certainly should have caught that.

Thorne

that should also be angelheaded hipsters, not angle