“If a man is called to be a street sweeper, he should sweep streets even as Michelangelo painted, or Beethoven composed music, or Shakespeare wrote poetry. He should sweep streets so well that all the hosts of heaven and earth will pause to say, here lived a great street sweeper who did his job well.” — Martin Luther King, Jr.

Working class heroes:

Mexico city’s army of barrenderos

‘We don’t sweep the streets just for ourselves… Our ancestors, the Great Aztecs, come from this place and now it belongs to all of humanity.’

By John Ross / The Rag Blog / August 26, 2010

MEXICO CITY — A small army of men and women in florescent orange and green uniforms pushing bright yellow carts hovers on the edge of the overflow crowd in the great Zocalo plaza of this city, ready to pounce. Whether it’s the 62 matches of the World Cup “FIFA Fan Fest” shown on giant screens for the diversion of the masses or a rally of tens of thousands of disgruntled citizens who have gathered to protest the policies of their government, the “barrenderos” are prepared to move in and haul away the mess the “fanaticos” have left behind.

“These Mexicanos are real ‘cochinos‘ (pigs),” kvetched my young pal Alejandro Daniel, a member of the corps of “barrenderos” or street sweepers who are charged with the hopeless mission of keeping Mexico City’s Centro Historico, the old quarter of this ancient capitol, free of debris, as he scooped up plastic cups, half-melted paletas (popsicles), the gnawed butts of tacos and “perros calientes” (hot dogs), several flattened plastic horns, and a sea of greasy waste paper, and artfully stuffed them into his cart.

Alejandro, 22, a second generation barrendero whose mom worked in the city’s street cleaning department before him, is one of 8,500 street sweepers on the Cuauhtemoc borough’s pay roll, 400 of them assigned to patrol the old quarter, a neighborhood which is roughly the configuration of Tenochtitlan, the island kingdom that was the crown jewel of the Aztec empire and is now listed on the UNESCO roster of world heritage sites.

The barrenderos work three shifts around the clock, but keeping the Centro Historico spic and span is an impossible job. By day, the neighborhood is a chaotic confluence of 2 million automobiles, trucks, buses, bicycles, and rickshaws and untold millions of pedestrians — government workers, ambulantes (freelance venders), tourists, demonstrators, and residents — who dump vast cordilleras of “basura” (garbage) onto the city streets.

Alejandro’s “tramo” or route extends down Isabel la Catolica, a narrow street where this writer has lived for the past quarter of a century, eight blocks north to the national pawn shop (“Monte de Piedad” or “Mountain of Piety.”) Along the way, the young barrendero sweeps up the gutters (the sidewalks are cleaned by residents and store owners), and dumps plastic public trash baskets lined up six to a block into his cart.

He also picks up garbage bags from private customers — this take-out service (“la finca“) is strictly prohibited by his bosses in the borough government but Alejandro’s salary is only 1,300 pesos every 15 days (“La Quincena“), approximately $100 Americano, and he desperately needs his finca to make ends meet.

The barrenderos are also charged with following demonstrations through the Centro (there are an average 3.2 a day), sweeping up after the “cochino” marchers, painting out “pintas” or spray-painted slogans scrawled on the walls of the ancient neighborhood, and ripping down leaflets posted by militants. “We leave the ones against (President) Calderon,” confides Alejandro, a partisan of former left mayor Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador.

The worst day of the year for the street sweeper is October 2nd, the annual anniversary of the 1968 student massacre (300 killed) in the Tlatelolco housing complex just north of the Centro Historico. For generations, students have marched to commemorate those who fell in the government-ordered slaughter, spray painting every surface in the neighborhood, battling riot police, and looting convenience stores. When the barrenderos try to wipe out the wall scrawls, they are attacked. “Once they sprayed me from top to bottom and then dumped my cart on top of me,” rues Alejandro.

Mexico City, the largest urban stain in the Americas with 23 million sentient human beings packed into its metropolitan zone, generates a bit under 20,000 tons of garbage daily, about 1.45 kilos of basura per chilango (Mexico City resident). The capitol, which holds a fifth of the population, accounts for a third of the country’s garbage.

Much of the effluvia is recycled by the workers themselves to augment their meager salaries and the leftovers buried in two pestilent landfills — the “Bordo Poniente” out on the dried bed of Lake Texcoco behind the airport in the east of the city and now dramatically running out of room, is thought to be the largest garbage dump on the continent.

Recycling is mostly the domain of the collectors — the barrenderos and the basureros or garbage men. At the dumps, “pepinadores,” garbage pickers, sift through the waste for recyclables that the crews have missed.

From the crack of dawn through high noon, elephantine green trucks swamp the inner city, picking up the residue from shops and restaurants, private businesses and working class colonias, their arrivals still heralded by the ringing of a brass bell.

The garbage men (there are no women although half the street sweepers are female) toss overflowing waste barrels into grinders mounted on the back of the trucks, dump buckets of industrial grease and organic slop, often spewing debris into the gutters for the sweepers to clean up.

Although the barrenderos and the basureros are fierce competitors for the city’s garbage, they have had to forge strategic alliances to get the job done. “We consider the garbage crews to be our companeros,” Alejandro affirms.

I follow Alejandro and his flailing broom through traffic as he darts down Isabel La Catolica, often squeezing between parked cars to retrieve a banana peel or a discarded newspaper. The barrendero wrestles the contents of the street trash baskets into his cart but hesitates outside the dozens of fast food franchises here in the Centro so that the hungry and the homeless can fish for discarded food first.

These days, he is often challenged by can collectors — with unemployment at a record high and old people scraping by on meager pensions, recycled cans bring in a few coins for the underclass. Alejandro is also wary of “pirates” who steal unguarded carts and brooms and swipe the barrenderos’ fincas.

The street sweepers’ brooms are emblematic of their “oficio” (profession) but lately they have become the source of labor tensions. Their bosses, bureaucrats in a city government that has been administrated by the left Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) for the past 13 years, insist upon buying commercial brooms rather than the picturesque bundled tree branches with which the barrenderos have historically swept the city’s streets. If the street sweepers want an old-fashioned broom, they have to buy or fashion it themselves.

Alejandro’s gaze is fixed on the gutter. Sometimes he finds coins or lost cell phones, but mostly these days the streets are littered with cigarette butts. Ever since this left-run city barred smoking in office buildings, restaurants, and bars, the streets have been converted into public ashtrays.

Between Uruguay and Carranza streets, the street sweeper bends to retrieve a plastic bag that has escaped from a nearby Sanborn’s department store and wrapped itself around a scraggly tree planted in a tiny square of dirt, one of the few green spaces in the congested heart of the Monster. Although a city ordinance now obligates dog owners to pick up after their curs, street dogs are attracted to these dirt patches and Alejandro has to step smartly to avoid the dogshit.

Just then a driver pulls up to curbside and throws open the car door without looking, a classic “portazo” that knocks the barrandero flat. I offer him a hand.

“Even though we wear these bright orange uniforms so we don’t get run down in traffic, people never see us,” he complains, “we are brooms to them — not people. Its like we are invisible.”

“Los Invisibles” is, in fact, the name of a troupe of barrenderos who do street performances around the Centro Historico.

“We see that we are underappreciated. Sometimes people are personally offensive to us. They call us ‘mugreros‘ (dirty ones) and much worse so we are trying to educate the public to respect us more,” explains Pia V., a founder of The Invisibles. “Our shows also give us an opportunity to make the neighbors more aware of their environment and encourage them to do recycling and help us keep the streets clean.”

Pia and Alejandro invite me to a rehearsal of Los Invisibles on Regina Street, a block devastated by the great 8.1 1985 earthquake here that the city has transformed into a pedestrian cultural passageway. A stage has been cobbled together by the community.

Moni, the diminutive mother of two girls (the kids have come out to see her perform) opens the show with a bouncy number, “Caminando Por El Centro“:

Walking through the Centro/I encountered a broom/that didn’t have an owner/so I started to sweep up Allende Street.

“When I start to sweep/I think about my family/of which I am the strong arm/that maintains them…”

The two girls jump up on the stage and embrace their mom.

Dani follows with a rant about “El Pinche Viejo” (“The Fucking Old Man”), a supervisor who is taking his time about assigning her a street to clean. She frets that she will miss her finca:

Tell me pinche viejo/how long do I have to wait/for you to make up your mind?

The barrenderos raise their brooms in a martial salute. Alejandro launches into a rap about “Derechos de Senoridad” (“Seniority Rights”):

There are people with too much money/while others don’t have enough to eat/the rich are the ones who make all the frauds/our job is to sweep up this black history…

Pia takes on the tourists who flock to the Centro and do not use the public trash baskets:

I ask you please/Not to dirty the streets/In whatever city you come from/And that someday you will remember us/Sweeping up our country.

Neighbors gather in front of the “vecindades,” the spruced up old slum buildings that line Regina Street and laugh and applaud. The barrenderos are popular figures in the inner city barrios of Mexico’s meotroplises, often seen pushing their carts and cans in the company of a string of mangy garbage dogs who live in the “depositos” or collection centers.

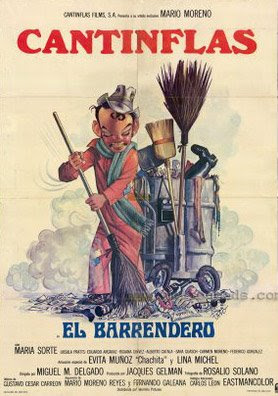

Street sweepers are intensely focused on the neighborhoods they clean and often the source of fresh “chisme” (gossip), the secret fuel that powers Mexican society. Back in the 1960s, barrenderos were often the source of popular troubadour Chava Flores’ urban ballads and the immortal Cantinflas’s final Mexican movie El Barrendero (1982) is about a heroic street sweeper who rescues a stolen painting he finds in the garbage from a gang of thieves.

But too often the city’s barrenderos are seen as little more than street furniture, part of the mob of shoeshine men, newspaper venders, organ grinders, buskers, beggars, “toreros” (freelance ambulantes), and “rateros” (street thugs) who fill up the streets of the Centro. Working class heroes are hard to find and the barrenderos certainly qualify.

The street sweeper brigades were an early feature of the city’s left governments. They came into their own after the two-year long renovation of the Centro Historico under Mayor Lopez Obrador that was financed by the world’s richest tycoon, Carlos Slim, who indeed grew up on these mean streets and is now the virtual owner of the old neighborhood with a reported portfolio of 160 buildings.

“We don’t sweep the streets just for ourselves,” Alejandro explains, “our ancestors, the Great Aztecs, come from this place and now it belongs to all of humanity.”

“When I was a kid I would go to the Alameda Park and the Zocalo with my family and I would wonder who sweeps up these places?” Pia remembers. “Now it is me. It is my responsibility. Although the people are rude to us and pretend not to see us, our city couldn’t breathe without our brooms. Everyone would be buried under the basura.”

[John Ross, the author of El Monstruo: Dread and Redemption in Mexico City, will be walking the garbage-strewn streets of San Francisco for the next weeks.]