The conspiracy in an Austin attic:

My first rad-confab

I had never seen marijuana and though I knew that it was prohibited, it didn’t occur to me that my new friends were seated in a circle to pass a joint around.

By Dick J. Reavis / The Rag Blog / August 19, 2010

[The Rag Blog has a lively online discussion group composed of friends and contributors. Many are veterans of the Sixties New Left and underground press and lately have been been sharing war stories of the early days. We intend to pass some of them your way. Journalist, author, and educator Dick J. Reavis admitted to the following.]

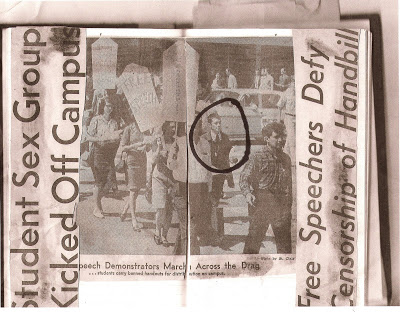

I joined Students for a Democratic Society by signing a card at a sidewalk recruiting booth outside Gregory Gymnasium at the University of Texas in Austin during fall semester registration, 1965. I was new to the campus and had never heard of SDS.

Perhaps because I told the students at the booth that I had spent the summer as a civil rights worker in Alabama, one of them invited me to what he or she may have called a meeting — but turned out to be a party. It was set for a Saturday evening, and I went by on my way to work.

My job was essentially that of a domestic servant. I was a photographer for Jack’s Party Pictures, a business on the Drag which sold pictures of Greek parties and dances. The night of the SDS gathering was my first day on the job.

The rad-confab was held at a two-story clapboard house near the corner of 17th St. and West Ave., where several SDS members lived. I presented myself, though a door to a kitchen, about 6:30 p.m. A young woman pointed me to a set of stairs that led — to an attic! But it didn’t bother me that, as things seemed, SDS might be a conspiratorial group.

A few feet from the top of the stairway I found six to 10 people seated on crates or boxes in a circle. With his back facing a dormer window sat the apparent chairman or guest of honor, Al Shahi, a fleshy, dark-skinned Iranian student who, I later learned, was sometimes the titular president of SDS.

One of the attendees explained that Shahi had received an order to vacate the country or face deportation. But the mood was that of a farewell party, not of plot to foil the immigration service.

It only took a glance for me to conclude that maybe I was in the wrong place.

The word “hippie” did not then exist, or hadn’t reached Austin, but my new-found peers were developing the style. The males had hair longer than customary and may have been mustachioed or bearded as well. I was clean-shaven, burr-headed and probably wearing tan slacks and a white dress shirt, the de facto uniform for Jack’s.

If sartorially I was clean-cut, philosophically I was disheveled, the opposite of my new friends. That summer in Alabama had upended my picture of life, and on that evening, I wasn’t sure if I was still a Baptist, or even believed in God, but I was ready to burn the country to the ground. Respectable white folks were either enemies or hypocrites and we who were young and Southern, I had come to feel, had to oust them and overturn the whole way of things.

Before many minutes had passed in that attic, I felt tormented by what I saw and heard. Why were people sitting in a circle, anyway? Why were they chit-chatting? When would the meeting begin, who would announce its agenda?

It seemed that I had been invited into a conspiracy whose purpose was merely to waste time. I had never seen marijuana and though I knew that it was prohibited, it didn’t occur to me that my new friends were seated in a circle to pass a joint around. I didn’t even know what a “joint” was.

Finally, if memory serves me right, some brave soul produced a penny matchbox of pot, then rolled, lit, and passed a joint.

Before it came to me, I begged off and went down the stairs, figuring that my fellow radicals would take me for a cop, though I was confident that their suspicions would pass. Within minutes I was at my first photo shoot, at a fraternity house only blocks away. The frats were just beginning to congregate; only two or three couples were on hand. A guy who acted as if he had authority sidled up me and said, “Why don’t you come back at a white man’s hour?”

I looked at him pretty hard for a second. I knew that I couldn’t strike him and would probably lose a fight if I did, and I didn’t think I could object to his terminology, because, essentially, I was working for him.

“Okay,” I said, and walked to my car.

A “white man’s hour” for work, had I tried to hire the frats to work for me, was probably equivalent to never, I figured. So I didn’t return.

Monday when I reported for a new assignment, owner Jack gave me a piece of his mind. “They told me that you promised to come back but you didn’t,” he said.

I nodded and made no excuses, knowing that, as a newbie, I wouldn’t be fired.

Thinking back on that day, I suppose that I owe the SDS celebrants an apology for crimping or stalling their festivities. But the way I also figure it, those frats owe me an hour or two of wages. I’d have shot pictures at their party, as I did at dozens of subsequent fetes that semester, had their representative not convinced me that he wasn’t worth serving.

[Dick J. Reavis, who became active in SDS and contributed to The Rag in Sixties Austin, is a professor in the English Department at North Carolina State University. His latest book is Catching Out: The Secret World of Day Laborers. He can be reached at dickjreavis@yahoo.com