Bicentennial mischief in the making?

The mysterious kidnapping of ‘El Jefe Diego‘

By John Ross / The Rag Blog / July 13, 2010

MEXICO CITY — Subcomandante Marcos, the quixotic mouthpiece for the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) who has not been seen in public for the past 19 months, has emerged as a possible suspect in the kidnapping of powerful right-wing politico Diego Fernandez de Cevallos, who was taken by unknowns at the gate of his ranch in the rural Queretero county of Pedro Escobedo this May 14th and remains in captivity.

Up until quite recently, the snatching of “El Jefe Diego,” as he is known by Mexico’s political class, has been ascribed to mercantile motives — sources close to the negotiations with the kidnappers indicate that the original $50 million USD ransom demand has been reduced to $30 million and the family of Fernandez de Cevallos is said to be selling off choice properties and a fleet of nearly 200 vehicles to raise the asking price. If the information is accurate, the ransom would be a record for Latin America.

Diego Fernandez de Cevallos is a former presidential candidate of the right-wing PAN party and a dark horse candidate to succeed current PANista President Felipe Calderon. Indeed one theory popular with Mexico City taxi cab drivers is that El Jefe Diego kidnapped himself to enhance his candidacy in 2012.

As the rightists’ standard-bearer back in 1994, Fernandez de Cevallos racked up nearly 10,000,000 votes but finished second well behind the PRI’s Ernesto Zedillo — the PRI which had ruled Mexico for 71 years ceded the presidency in 2000 to the PAN’s Vicente Fox, Calderon’s predecessor.

During the reign of reviled ex-president Carlos Salinas (1988-94), El Jefe Diego served as head of the nation’s senate and cut frequent deals with the PRIista, signing off on the burning of ballots cast in the fraud-marred 1988 election that most Mexicans believe was won by leftist Cuauhtemoc Cardenas. As quid pro quo, the PAN was gifted with its first ever governorship (Baja California) and Fernandez de Cevallos got a vacation home in the ritzy Punto Diamante neighborhood of Acapulco that the family is now trying to unload to meet the ransom demand.

A fierce litigator who inevitably defended the interests of the oligarchy, El Jefe Diego has been frequently accused of influence peddling, the suspected source of his immense fortune. The abrasive Fernandez de Cevallos with his trademark bristly beard and Havana cigar clenched tightly in his jaws has nurtured many enemies both as a litigator and a lawmaker. Among them is Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO), the left PRD’s presidential candidate in 2006 who is thought to have edged Calderon only to have the victory stolen from him in the vote count, and the announced left candidate for high office once again in 2012.

When AMLO was the wildly popular mayor of Mexico City, El Jefe Diego got his hands on a series of hand-made videos in which a crooked contractor doles out fistfuls of Yanqui dollars to Lopez Obrador’s former personal secretary and other high-ranking PRD officials. According to the contractor, after consulting with his old pal Carlos Salinas, Fernandez de Cevallos had the tapes delivered to Televisa and TV Azteca, Mexico’s two-headed television monopoly, where they were repeatedly aired in a failed effort to derail Lopez Obrador’s presidential bid. In his latest book, The Mafia That Took Over Mexico, AMLO lists both Salinas and El Jefe as leading members of the Mexican “mafia.”

Diego Fernandez de Cevallos is not popular with the Zapatista Army of National Liberation either. In the wake of the Zapatistas‘ 1994 rebellion in Chiapas, El Jefe Diego repeatedly dissed the ski-masked Subcomandante Marcos and declared that he would never agree to negotiate with “Indians who wore socks on their heads.” Later, he would reject the Zapatistas‘ Indian Rights Law, arguing that the recognition of indigenous uses and customs would lead to the restoration of “human sacrifice.”

Within days of the kidnapping, Fernandez de Cevallos’s family asked Mexico’s Attorney General to suspend his investigation into the whereabouts of the politico, pending negotiations with his captors whose Harry Potter-like e-mail address identifies only as the “Mysterious Disappearers.”

Communication with the authorities has been channeled through Fernandez de Cevallos’s law partner Antonio Lozano Gracia, himself a former attorney general. The current AG, Arturo Chavez Chavez, yet another Fernandez de Cevallos law partner, now meets with Lozano three times a week to review developments in the case.

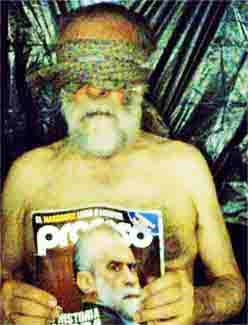

From all accounts, communication with the “Mysterious Disappearers” has not been fast paced. A cell phone photo of Diego, blindfolded and naked from the waist up, was sent via Twitter May 20th, probably to prove that he was still alive. What is apparently the same photo was sent again June 10th but now Diego was holding a copy of Proceso magazine with his mug on the cover dated May 23rd. Photoshop can work wonders.

The delivery also included an eight-page letter written in a firm hand that graphologists conclude is El Jefe‘s handwriting, and addressed to Diego’s son, also named Diego, lamenting that his father was “living in hell” and expressing fears for his mental health. Fernandez de Cevallos implored his family to move quickly to post the asked-for ransom.

According to one informant quoted in the left daily La Jornada, Fernandez de Cevallos spoke directly with his son July 12th but no details of the conversation were disclosed. “Chisme” (gossip) floating around the Internet has the family reluctant to come up with the ransom because they don’t want the irascible Jefe freed to further complicate their lives. Another chisme has the Mysterious Disappearers so exasperated with having Fernandez de Cevallos on their hands that they will soon release him free of charge.

In a surprise late July statement released to the Mexican press, Attorney General Chavez Chavez’s office revealed that investigators have concluded that the motives for the kidnapping were political and not mercantile as had been broadly believed.

The Center for Investigation and National Security (CISEN), the nation’s lead anti-subversive intelligence agency, pointed a finger at the long-lived guerrilla Popular Revolutionary Army (EPR), a cell of which operating as the Revolutionary Democratic Tendency-Peoples’ Army (TDR-EP) has been active in the Bajio, the rich agricultural region in central Mexico where Fernandez de Cevallos was taken, for the past 20 years. In 2007, the EPR claimed credit for the bombing of PEMEX pipelines in Queretero and Guanajuato in retaliation for the disappearance of two of its historical leaders.

The EPR is famous for financing its operations through political kidnappings, most notoriously the 1994 snatch of Alfredo Harp Helu, the president of Banamex, Mexico’s oldest bank (now a branch of Citigroup), and cousin of the world’s richest tycoon Carlos Slim.

Negotiations for Harp Helu’s release were channeled through a defrocked Catholic priest Maximo Gomez of Atoyac Guerrero who one informant close to the negotiations says is again involved in the current bargaining between the family and the kidnappers. Harp Helu was released after six months in captivity for a reported $14 million USD ransom. According to newspaper accounts, the EPR invested the boodle in heavy caliber weaponry.

Armed to the teeth, the Popular Revolutionary Army made its public debut June 28, 1996, along the Costa Grande of Guerrero on the first anniversary of the massacre of 17 farmers and then launched a short-lived campaign against military and police installations that extended through six states. The CISEN reports that the EPR has more recently financed its activities from the kidnappings of 40 industrialists and ranchers in the Bajio region.

Intelligence sources quoted by La Jornada cite one Constantino Alejandro Canseco AKA “Comandante Jose Arturo” as the key organizer in the taking of El Jefe Diego — the pseudonymous “Jose Arturo” was the most public EPR spokesperson during the guerrillas‘ 1996 campaign, meeting with the press at least twice at training camps in the remote Huasteca mountains of Hidalgo state.

Canseco’s brother, Felipe, a former guerillero and political prisoner, calls the accusations “absurd,” insisting Constantino was shot twice in the heart during disturbances at Oaxaca’s Benito Juarez University in 1976 and has been disabled ever since. Both Cansecos and the former rector of the university Felipe Martinez Soriano later formed the PROCUP, a guerrilla foco largely known for urban bombings. The PROCUP is thought to be at the heart of the EPR, a coalition of 14 small guerrilla bands that has since split into separate armed factions.

During its heyday, the Popular Revolutionary Army had a quarrelsome relationship with the EZLN, then the nation’s topdog insurgent army. When Subcomandante Marcos vehemently rejected the EPR’s offer of solidarity, Comandante Jose Arturo argued that Marcos was trying to fight a revolution with poetry and made fun of the pipe-smoking Sup.

But the kidnapping of Diego Fernandez de Cevallos suggests that the two have since reconciled and joined forces to pull off a spectacular operation on the eve of the nation’s celebration of its bicentennial of independence and the centennial of the Mexican revolution.

Evidence of Subcomandante Marcos’s involvement in the kidnapping of El Jefe Diego is exclusively circumstantial. In the Zapatistas‘ Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle issued in June 2005, Marcos called upon his supporters to set their sights on the 2010 twin centennials as a platform from which to launch a new Mexican revolution. In fact, the EZLN’s “Other Campaign,” also a creature of the “Sexta,” was initiated precisely to forge alliances with other radical groups in preparation for a new mass uprising in 2010.

But in 2010, Subcomandante Marcos has vanished from the political map. His last public appearance was in January 2009 when he spoke briefly at the “Digna Rabia” (“Dignified Rage”) forum in San Cristobal de las Casas and he has issued no public communiqués in the past 19 months. Chiapas’s many daily newspapers, all of which suffer a striking dearth of veracity, have frequently reported that the Sup has split with the largely disarmed EZLN and left the state for more radical pastures.

Wherever the truth lies, Subcomandante Marcos has surely not been idle for the past year and a half. This writer, the author of four volumes on the Zapatista rebellion, has often speculated on rapprochement with the EPR in preparation for some major mischief during the upcoming bi-centennial and centennial celebrations.

Marcos has a vivid model for the Jefe Diego caper. In the first days of the January 1994 Zapatista rebellion in southeastern Chiapas, rebels captured the former governor of the state, Absalon Castellanos Dominguez, a general who had ordered brutal massacres in indigenous communities and who was much hated by the Indians.

Absalon was held for a month at Guadalupe Tepeyac, the rebel command’s headquarters, before being taken before the community for a public trial where he was adjudged guilty of abusing and killing Indians and stealing their land and was sentenced to 30 years in an indigenous village hauling water and firewood.

A flurry of back-channel negotiations with the “mal gobierno” (“bad government”) followed and the EZLN then pardoned the General on the grounds that he would now have to spend the rest of his life bearing the shame of having been pardoned by the very people he had so abused.

The ex-governor was released on a jungle road in early February 1994 in a nationally televised extravaganza — for many Mexicans the ceremony surrounding the release was the first time they had even seen the Zapatistas. The blindfolded Absalon was marched down the dirt path accompanied by the Zapatistas‘ Major Moises and an unidentified woman comandante and handed over to the Salinas government’s peace commissioner, Manuel Camacho Solis.

Neither the conditions of Absalon’s release nor the amount of the ransom paid out was ever divulged, but two weeks later public negotiations between the EZLN and the mal gobierno began in the Cathedral of San Cristobal de las Casas.

For Subcomandante Marcos, the hoopla generated by Absalon’s kidnapping and release proved a media coup that put the EZLN at center stage in the Mexican political dynamic and won national and international recognition that the rebels have rarely been able to replicate.

Curiously, in an interview with Proceso at the end of July, Max Morelos Martinez, a Bajio lawyer who is privy to communications between the kidnappers and Fernandez de Cevallos’s family, speculated that El Jefe‘s captors intended to conduct a public show trial charging him with many crimes against the Mexican people after which a reasonable ransom would be paid for his release.

The language utilized by the Mysterious Disappearers in e-mails directed to Pepe Cardenas, a political columnist for the daily El Universal, is revealing. In one note, the Disappearers speak of El Jefe Diego as “the Archduke of Escobedo” (where the ranch from which he was kidnapped is located), a phrase that rings a bell with this assiduous reader of hundreds of Subcomandante Marcos’s poetic, humorous communiqués sent to national publications in the early years of the rebellion that mordantly lampooned Mexico’s political class.

Indeed, the title that the kidnappers have assigned to themselves, the “Mysterious Disappearers,” invokes the Sup’s unique, mocking literary style.

Lawyer Max Morelos Martinez, who has been the go-between in several negotiations between victims’ families and kidnappers in the Bajio and who has talked personally with the likes of Daniel Arizmendi, “the Earchopper,” who would often send his victims’ ears or fingers to their families, observes that the tone adopted by the “Misteriosos Desaparacedores” doesn’t sound authentic. When kidnappers demand ransoms, their language is always cut and dried: “send us x amount of money or you’ll get your kid’s ear in the mail tomorrow.” Click. They don’t have much of a sense of humor.

An E-mail sent last week (Aug. 5th) to the “Misteriorosos.Desaparacedores@yahoo.com” inquiring after Subcomandante Marcos’s well being did not elicit a response. When the message was re-sent the next day, the account had been closed down.

Down the years, Mexico has had its share of political kidnappings. Back in the 1970s, urban guerrillas snatched the U.S. Consul in Guadalajara, eventually exchanging him for a plane to fly political prisoners to Cuba. The September 23rd Communist League kidnapped many wealthy industrialists in Monterrey, occasionally killing them in the process. The taking of Harp Helu by the EPR was the most notorious in recent years but many kidnappings of influential Mexicans such as former Interior Secretary Fernando Gutierrez Barrio in 1997 have never been publicly disclosed and the victims were quietly released once the ransom had been paid off.

As President Felipe Calderon gears up for his gala, multi-billion peso bicentennial celebration of Mexican Independence this September 15th, longtime observers of Subcomandante Marcos’s media exploits cannot help but wonder if the Sup is about to steal the spotlight from the Mexican government once again?

John Ross, author of El Monstruo: Dread and Redemption in Mexico City (“gritty and pulsating” New York Post), will be otherwise occupied for the next month. These dispatches will be issued every 10 days until he returns to Monstruolandia. For queries, kvetches, or faint praise contact johnross@igc.org