Up from the barrio:

A Chicano son of San Antonio

Reflects on El Movimiento

By Gregg Barrios / The Rag Blog / July 6, 2010

See video of Gregg Barrios’ interview with David Montejano, Below.

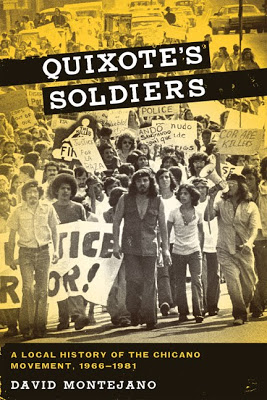

[Quixote’s Soldiers: A Local History of the Chicano Movement, 1966-1981, by David Montejano (University of Texas Press, 360 pp., $24.95, paperback).]

SAN ANTONIO — In Quixote’s Soldiers: A Local History of the Chicano Movement, 1966-1981, author and educator David Montejano posits that San Antonio local history provides a microscopic look at the Chicano civil-rights movement and the social change it forged.

In the book’s preface he declares: “As a San Antonio native, my narrative explanation has a certain autobiographical quality to it.” Montejano grew up in “a West Side subdivision built in the 1950s, in the Edgewood District, one of the poorest in the state and later made famous by its successful challenge of the state’s educational financing schema. My neighborhood was a poor working class surrounded by poorer neighbors on three sides.”

Still, Montejano’s parents made the decision to send him to Catholic school since it provided a better education. He attended Central Catholic High in the mid-1960s along with George and Willie Velásquez and Ernie Cortés, all of whom later played important roles in the movimiento. While future San Antonio mayor Henry Cisneros also attended the Catholic high school, Montejano considers Cisneros a beneficiary but not part of the Chicano movement.

The seeds of Montejano’s activism were planted early on: “The Brothers [of Mary] taught a humanistic philosophy of brotherhood that later became liberation theology.” He was drawn to those teachings with their attention to poverty and social inequality.

His freshman year at then South Texas State University in San Marcos proved important to the young man’s education: He witnessed a clash between a Mexican service-station attendant who had refused to put gas in a car of drunken cowboys and how it was effectively defused. Later, when a caravan of striking farmworkers came through the small college town, Montejano joined them.

He transferred to the UT Austin campus where he became involved in the counterculture, anti-war, and black civil-rights movements and helped collect petitions to get La Raza Unida Party on the state ballot. His activism led to his arrest during a student protest in Austin against service-station owner Don Weedon.

Montejano is now a professor of ethnic studies at the University of California, Berkeley. He is also the author of the award-winning Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1936-1986, and the editor of Chicano Politics and Society in the Late Twentieth Century.

Unlike many academic books steeped in jargon, Quixote’s Soldiers is a fascinating look into the making and undoing of el movimento chicano and more specifically traces “some parts and tactics to its history of the Chicano movement in San Antonio.”

We spoke to Montejano during a brief visit upon the publication of Quixote’s Soldiers.

In the first part of Quixote, you point out how San Antonio’s gang problem in the 1960s wasn’t helped by how it was viewed by the authorities.

There was a real gang problem, but it was exacerbated by the perception by authorities that all the working- and lower-class youth in the barrios were gang members. This included the social scientists that would come from the outside to study the youth. They would come in with this assumption that was an oversimplification and false. But there were gangs and conflicts that were passed on from generation to generation. But when I talk about self-identified gangs, I’m speaking of a very small number, perhaps 10 percent.

Your account of how Mexican-American student activists [many from St. Mary’s University] along with politicized gang social workers mobilized disenfranchised barrio youth is fascinating. And yet organizations like [the Mexican American Youth Organization] and [the Mexican American Unity Council] quickly faced opposition from the Anglo and Mexican-American political elite.

The MAYO leadership and the batos locos of the barrio hanging out truly influenced one another. But once Henry B. shuts down places like [the alternative] La Universidad del Barrios, these young college kids get involved in politics. Symbolic politics. The batos were geared to addressing local issues: police brutality, drug trafficking. If they had remained together who knows how this could have developed.

Where do the Brown Berets fit in the movimiento? I remember there were some Wild West types in the Berets and a few informants as well.

Wild West Side types. The first part of the book deals with barrio youth and gang warfare and how they become involved in the movement and eventually form the Brown Berets. The [academic] literature places little emphasis on the barrio or the batos locos that formed the Berets. The first confederation of the Berets in San Antonio is based on the old gang boundaries and identities.

Did Saul Alinsky’s community-organizing strategy have a bigger influence on MAYO and MAUC than the Mexican Revolution?

The Mexican revolution provided the symbols and the songs [laughs] and the color, but without question, Saul Alinsky. And, of course, the Black Power movement.

Why did the rhetoric turn to the confrontational “Kill the Gringo!”?

Jose Angel Gutiérrez, Nacho Perez, Mario Compean, [and] Norman Guerrero all believed that the only way you could wake up our people was through this confrontational, provocative language. There was an image that we were a passive people, the sleeping giant. Estos batos were going to wake up the sleeping giant through their rhetoric. This scared the hell out of the political establishment — the Anglo and Mexican-American elite.

You devote several chapters to Henry B. Gonzalez [influential San Antonio politician who served in Congress, 1961-1999], who viewed the Raza movement as racist. Still he was also considered a hero for his liberal stance on issues. Why this division? Was this old crab trying to keep the others down? Political posturing?

That’s a good question. I wrestled with that. Henry B. would say it was out of principle. He opposed any politics based on ethnicity. He thought it was equivalent to corruption. His adversaries believed it was based on his alliance with the [Good Government League], that Henry B. had turned his back on the people who had helped elect him. And so that’s the basis for a lot of animosity between Henry, Albert Peña, Joe Bernal, and others. So was it just principle or was it just money? Was it patrón politics we’re talking about? I’ll let the reader figure that out.

Did the strong showing of Mario Compean [the Committee for Barrio Betterment candidate for mayor in 1969] against GGL incumbent Walter McAllister spark the notion that we could elect our own candidates and create a political party like Raza Unida?

I definitely believe that. It is not just my belief but that of others that I have interviewed — the fact that CBB was able to place second without any money and just campaigning in the barrios, using mimeograph machines, going to the quinceañeras, clearly a low-budget affair. And they clearly won against the GGL in the West Side. And not by tiny margins; there were some substantial margins. This results in Mario Compean declaring himself Mayor of the West Side.

I was a teacher at Lanier High School at the time. I saw the sense of pride and identity in my students, not only in having Latino teachers, but in the rise of a Chicano renaissance in the arts. While your book centers on the political aspects of the movimiento, I believe both go hand in hand; all art in a sense is political.

It’s true, I do in passing mention the teatros, the art, the flourishing of literature. And the identity formation. Now we are Chicanos, Chicanas. That’s a new vocabulary. A new identity. And all of that is buttressed by this cultural renaissance. There is no question about that.

Was José Angel Gutiérrez’s strategy of building the Raza Unida Party county by county instead of running candidates in state elections ultimately the road that should have been taken?

In hindsight it would have been the better alternative. At the time we wanted everything and we wanted it now.

But were we prepared to accept the responsibilities that come with those victories?

We were young. We were 20-something. We were naive. We didn’t know a lot of these things, we just wanted someone elected. And in many cases we didn’t know what to do afterward. We had no plan other than that it might lead to some sort of liberation.

What is the lasting legacy of the Chicano movement?

Certainly the opening up of universities in the creation of Chicano Studies, because that is where we get our history, our art and literature. And in San Antonio, the establishment of UTSA might be considered a logro for us. The changing from at-large electoral politics to single-member districts was a very important change. The building of our political and community capacity by grassroots organizations — COPS and Southwest Voter Registration Education Project.

Bless Willie [Velásquez] and Ernie [Cortés].

They increased the political capacity of these barrios and the result of all that in tangible, concrete results are parks, housing, flood control, drainage. Those are some of the accomplishments. And I think besides the election of Henry Cisneros in 1981 that symbolizes the changes.

The other major change is the emergence of Chicanas in leadership positions. I mean visible leadership, no longer being in the supportive background but now being upfront, leading the organizations, holding the press conferences, running for office. That to me is an important change.

A few wrong turns

In one of Quixote’s Soldiers’ most interesting and bound to be controversial chapters, Montejano focuses on three individuals as examples of failed leadership. Fred Gómez Carrasco, Ramsey Muñiz, and Henry B. Gonzalez dominated media coverage in Texas in the 1970s — representing a “Mexican” voice or presence to the larger public.

Montejano writes that some may question his selection of these three men as arbitrary and unreasonable:

The first was a convicted killed and drug dealer, the second a fallen political star, and the last a respected liberal congressman. [F]or better or worse, they represented different paths leading up and away from barrio poverty and isolation.

Fred Gómez Carrasco, the chivalrous drug “don,” had been a major heroin supplier for the barrios and ghettos of San Antonio and other points in Texas. Despite the romanticization of his life as a narco-traficante, Carrasco must be remembered as the genius organizer behind a drug operation that tranquilized and criminalized countless barrio and ghetto youths. In short, Carrasco played a critical part in undermining the Chicano movement in the poor, working-class barrios. Yet his last-minute political testaments, given before his staged death, suggests there could have been a different path.

Ramsey Muñiz, athletic star, charismatic leader, and two-time gubernatorial candidate for the Raza Unida Party, stumbled and then self-destructed, taking along with him the fortunes of the party. What happened? [Muñiz was charged with conspiracy to smuggle drugs from Mexico to Alabama.] Yes, it was a setup by the authorities, but how could Muñiz have walked into it? Was the temptation so great? Was it hubris? Ten years after serving time for his first two convictions, Muñiz was arrested and convicted on a third drug charge. As a result, Muñiz has been permanently incarcerated. The loss is irrevocable. What remains is a memory of those inspiring years when Muñiz moved 200,000 voters to believe in a “united people.”

Henry B. Gonzalez, an American of Spanish surnamed descent who held an idealistic “color-blind” view of the world was so upset with the Chicano ethnic demands that he actively opposed the Chicano movement. He was successful in defunding MAYO, forcing MALDEF to move from San Antonio, and restricting MAUC activities. Was it principle that moved his opposition, personal pique at movement rhetoric, or simply interest in maintaining political control? Gonzalez has been charged with undermining the Chicano movement, yet that responsibility must be partitioned among many.

Montejano concludes:

Perhaps this does lead to a judgmental question after all. Can we judge which path was the most flawed? [W]hich is worse, a flawed journey, a flawed decision or a flawed vision?

[San Antonio poet, playwright, and journalist Gregg Barrios is on the board of directors of the National Book Critics Circle. His new book of poetry, La Causa, appears in September and his play I-DJ premieres in October. Gregg wrote for The Rag in Sixties Austin. This article was also published in the San Antonio Current.]

- Find Quixote’s Soldiers by David Montejano on Amazon.com.

Wow! Thanks Gregg for the interview. Thanks to the author for the history on el movimiento en San Antonio. -Alice

A relatively minor event that illustrates that the impulse for protest and rebellion was strong on the West Side before the Chicano movement was born: a well liked and fair-minded principal at Edgewood High School, Anglo but not racist, at least not overtly so, was forced out of his job in the summer of 1958. (I was a student there at the time, with one year to go before graduation.) A member of the school board told some influential students that the man hired to replace him, who had been teaching in small-town South Texas, had made some clearly racist remarks in his job interview — “I know how to handle Mexicans” is one comment I remember hearing about. Some students were actively planning a strike in protest until the school board member talked them out of it. The students weren’t kidding though and I think they would otherwise have carried it out. Imagine: a student strike on the West Side in 1958. Their younger siblings and cousins actually did so ten years later.

Later that year Henry B. Gonzalez made a speech in an assembly at Edgewood, the most memorable part of which was a folk saying, something to the effct that, “Just because a cat is born in an oven doesn’t make it bread.” His meaning was pretty clear.

David Morris