Tea for two:

Peradventures in duopoly capitalism

By Marc Estrin / The Rag Blog / June 20, 2010

Many voices on the left complain about our “one-party” system, the Replutocrats, the entrenched and ubiquitous party of the rich. And indeed, for the media, the word “bipartisan” comes haloed in angelic light, while with the selfish and ragged “partisan” comes the stink of sulfur.

“Bipartisan” — that is, both-parties-as-one — is the way of virtue in contemporary America. Yet — as if we still had two parties — we continually witness a gaudy display of accusers vs. defenders, of hand-sitters vs. applauders, of gloaters vs. clobberds, and the nation seems relieved that power was balanced, that “democracy” triumphed, that the system worked. What’s going on? Do we have one party or two?

The answer is not as simple as the question, and for a subtle analysis we might best turn to Jean Baudrillard, the fabulously inventive and therefore despised postmodern French philosopher, best known for his analysis of false realities. The word “democracy” is a language-sign to be interpreted, and as with all signs, there are four Baudrillardian functions it can serve:

- Some signs are “reflections of a basic reality” — as is common in scientific or referential language.

- Some signs “mask and pervert a basic reality” — as when an MX missile is dubbed “Peacemaker,” or the current economy seen as “strong.”

- Some signs “mask the absence of a basic reality” — as when highly processed supermarket foods are labled “natural and delicious.”

- Finally, some signs “bear no relation to any reality whatsoever: they are their own pure simulacrum” — as in the incessant contemporary production of images with no attempt even to ground them in reality. Do you drive a Lexus, an Acura, an XL300…?

So then we have the word “democracy.” What of democracy, the great Enlightenment goal? Is there now only a democratic simulacrum, combining elements 2, 3, and 4 of Baudrillard’s list?

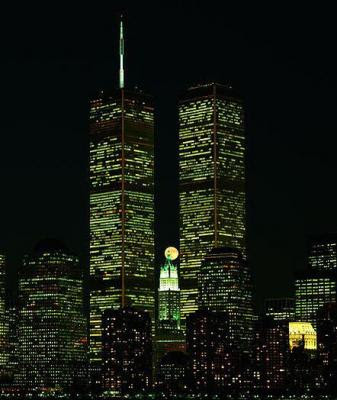

The Two Towers

As might be expected, Baudrillard takes a unique approach to this question. Democracy, finally, is a system of choice-making in which a supposedly informed electorate chooses its representatives from among a menu of ideological options.

Most critics focus on the dumbing down of the electorate, the false consciousness purveyed by the media, etc. Baudrillard, however, focuses intently on the menu. He asks a strange and pregnant question: “Why were there two towers at New York’s World Trade Center?”

All of Manhattan’s great buildings, he says, were once happy enough to affront each other in competitive verticality, the result of which was an architectural panorama in the image of the old capitalist system — all buildings attacking one other.

But this image has changed completely in the last few decades. Buildings now rise compatibly, no longer suspicious each other. The new architecture speaks of a system in which competition has been traded in for the benefits of collegiality. The fact that there were two World Trade Center buildings symbolized the end of old-style competition, the end of all original reference.

Paradoxically, if there were only one building, or competing forms, actual monopoly would not be incarnated; we see how it stabilizes on a dual form. For the sign to be pure, it has to duplicate itself…. (see Simulations, pp. 135-6)

No more competition. Can this be true? Is this Capitalism as we know it? And how can democracy function without choices?

The Obama phenomenon bears out, and best illustrates, Baudrillard’s predictions from the Eighties. Is Mr. Hope and Change a Republican or a Democrat? Will his possible passing in the next election change anything? Short of small symbolic gestures, would a President Palin serve a different master? Clearly not. The government may change, but the State allows no such changes: Power is not Power for nothing.

But a buck-naked monopoly of power will never do. Wrong symbol. Not palatable to the masses. Instead, the state is run by a system which gives an illusion of choice.

“Advanced democratic” systems are stabilized on the formula of bipartisan alternation. The monopoly in fact remains that of a homogeneous political class, but it must not be exercised as such. Because a one-party totalitarian regime is an unstable form, our “democracy” is accomplished in the back-and-forth movement of the two terms which activates their equivalence, but allows — because of their minute differences — a public consensus to be formed and the cycle of representation to be closed.

The “free choice” of individuals which is the credo of democracy, leads, according to Baudrillard, to precisely the opposite: the vote becomes a functional toss-up, resembling Brownian movement of particles. “It is as if everyone voted by chance, or monkeys voted.” (Simulations, p. 132)

There are “polls,” there is occasional alternation of power “at the top,” a simulation of opposition between two parties — never mind the equivalence of their objectives, and the reversibility of their language. The Dems can bail out the bankers, the Repubs can claim to represent “the people.” It could and should be the other way round, but…

Marx predicted that open competition would lead to the large devouring the small, up to the end result — monopoly. Baudrillard counters that it is not monopoly which is the end stage, but duopoly, the twin towers, the “tactical doubling of monopoly.”

Power is absolute only if it is capable of diffraction into various equivalents, if it knows how to take off so as to put more on. The same money finances Democrats as Republicans. Whoever wins the vote, Power wins with the winner. As Jay Gould once asserted, “I don’t care who people vote for, as long as I get to pick the candidates.”

Baudrillard’s notions of duopoly seem to me to be indisputable, and a related comment of his seems both hopeful and ominous: “You need two superpowers to keep the universe under control: a single empire would crumble of itself.”

[Marc Estrin is a writer and activist, living in Burlington, Vermont. His novels, Insect Dreams, The Half Life of Gregor Samsa, The Education of Arnold Hitler, Golem Song, and The Lamentations of Julius Marantz have won critical acclaim. His memoir, Rehearsing With Gods: Photographs and Essays on the Bread & Puppet Theater (with Ron Simon, photographer) won a 2004 theater book of the year award. He is currently working on a novel about the dead Tchaikovsky.]

The conditioning begins early for american voters. Parents send their kids to the government schools for a government education. If there were a choice, the government schools would only educate the marginally educatable. They would produce the landscape workers and the walmart checkers. Real schools would produce the thinkers, doers, and innovators.

The government eliminates choices. aka our national retirement system which is a joke and a sham of an investment. It only exists because we have no choice but to fund it. There is no choice in Healthcare since the government creates small regional monopolies and eliminates any meaningful competition.

While progressives scream for larger and more encompassing governments so they can better legislate social and economic justice, the actual result will be the death of meaningful innovation, stagnation and freedom to choose.

I prefer the chaos and barbarism of truely free choices.