WAGNER — OI!

By Marc Estrin / The Rag Blog / May 24, 2010

I didn’t begin “getting into” Wagner till I was 30ish. Who had the time for five-hour operas? And who had the money for 12- or 15-LP sets, or fifty bucks a pop for way-high at the Met? Forget it. Plus I didn’t even like opera, and still mostly don’t.

And what Jew could become a fan of Hitler’s favorite composer? My father wouldn’t even ride in a Volkswagen. Nevertheless, he did name our first family car, a 1950 Dodge, Brünnhilde. I should have known some interesting paradoxes were at large.

Jews, however, are big on Jewish guilt, so sometime in the mid-sixties, to make up for my reprehensible ignorance, I taped a Ring-cycle (at slowest speed, fidelity trumped by pennypinching) and discovered that this stuff did need some looking into. Quite interesting, it was. Quite.

As a musician, I was already familiar with the short, commonly played selections. I loved the various preludes and overtures — the complex stateliness of Meistersinger, the ethereal spirituality of Parsifal and Lohengrin, the drunken passion of Tristan. I was well aware of the revolutionary role of RW in western musical history — his breaking open the tonal paradigm, and clearing the path for complex contemporary music. But other than that, I hadn’t “gotten into” him — which would involve serious listening to, and study of, the operas.

Teaching at Goddard, I had the opportunity to do just that. (In the Goddard model, without departments, one could teach what one wanted to study.) I offered a course in The Ring where we listened with scores, studied the texts, read the criticism and Jungian analyses, and “grokked” the work. THAT was “getting into” it. I didn’t need any more convincing. Even putting its anti-capitalist nature aside, The Ring is big, deep stuff, just meant for me.

It was inevitable that crazed Wagnerians would show up in my fiction. So I share with you in honor of Wagner’s birthday, a little section of a vast chapter from my Insect Dreams.

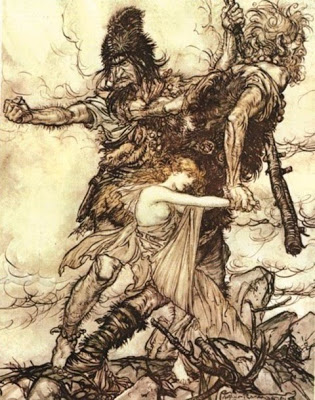

Gregor Samsa, a six-foot, talking cockroach, having just made a disastrous attempt at lovemaking with Alice Paul, has come to see Dr. Lindhorst about amputating his middle legs so that he might be more attractive to women. Lindhorst tries to dissuade him with the story of Pygmalion — complete with all its subsequent disasters — but Gregor decides to go ahead with the body-sculpting. Gregor is strapped to the operating table, and Lindhorst’s assistant, Miss Mozart, is called in.

I think this will excerpt tolerably, but should you want to see the whole, you can probably find the book at your library (it won all sorts of awards), and you’ll certainly find it at Amazon. Here’s the scene:

Gregor, Love is brother to his sister, Death. Eros and Thanatos, my friend. Longing always leads somewhere, and that somewhere is not always longed for. You must appreciate this — deeply — before you take an irreversible leap of mutilation in the service of love. If you understand and truly accept, your tissues will heal. If you do not understand, if you do not truly accept, you will carry yet another unhealing wound.” He paused to let his words sink in. “Miss Mozart, you may begin.”

The slim, intense woman took off her shoes, and sat down at the Bösendorfer, barefoot. Smoothing back the sides, and reaching behind her neck, she encircled the long fall of her golden hair with her fingers, moved it from her gown, and let it fall loosely onto her half-bare back. Though Gregor could see every detail with his immense peripheral vision, he felt himself drifting back into a hazier space deep inside his cuticle. Long echoes of Lindhorst’s hypnotic voice rippled slowly in circles of ever-softer sound.

Miss Mozart placed her right hand on the keyboard. The first gentle A reached up a plaintive minor sixth, and hung there, suspended in non-time, until it’s own weight eased it down to the supporting net of the note below — only to immediately fall through that net — oh surprise! — to the accented half step below, the awe-full D# of the Tristan chord, the chord of chords, that miraculous find of ambiguous, melancholy longing. Miss Mozart’s left hand joined her right to urge the F and B below, while her right fourth finger struck the G# that would resolve upwards, and upwards again beyond what might have been its goal. The Tristan chord, F-B-D#-G#, a chord so extraordinary that one can search in vain through music to find its like. Search was its name, and its mode, and its function. Search. But for what? The beauty of despair? The despair of beauty? What trembling question was being asked by this voice in the night? In the long pause which followed, Lindhorst whispered,

“Be in the silence, Gregor. Let the sweet pain soak in at your soft joints.” Then he signaled to Miss Mozart to continue.

The second phrase, a step higher, infinitely slow, exaggeratedly, tormentingly slow, left Gregor hanging as did the first, the Sehnsuchtsmotiv, the Leitmotif of Longing, calling him from the vast darkness of What. His wound began to weep into its new dressing. His dorsal gland began to moisten. The meat at his leg joints began to soften, as if to bid welcome to the knife.

“Something is dissolving, Gregor. What is it? Don’t answer.” He couldn’t have.

A third time the phrase called out, higher still, and longer, reaching upwards by two more notes, as if its fingers were stretching from an already outstretched hand.

“It hurts, my friend, does it not?”

As if to answer, the phrase returned, the same last, rising pattern, an octave higher, and then only the last two notes, a half-step reaching upward, and once again, the two reaching notes, an octave above, harmonic tension so great as to be humanly unbearable. And yet it hung there, radiating, in the silence — until beginning again, it pushed beyond itself, and with a final leap, reached beyond itself, above and below, to a land that could be footed, an almost safe place — an accented chord of F-A-C — but with a B above, a skyhook which let gently go, and allowed the hearer — and the universe — to collapse down to the floor of an ever-rising, but graspable flow of molten melody, the Motif of Love.

“Now you can swim, Gregor. Your wings are beginning to spread.” And indeed, G could feel pressure at his back, once associated only with sexual excitement, but now with something more mysterious, sexual in part, but as larger as the sea is to the drop. Miss Mozart’s fingers called forth the Bösendorfer’s magic, and the melody rang forth in quiet, sensuous richness, as if from twelve pianissimo cellos, though there was not a cello in sight.

The clock had ticked off ten minutes, but there were no minutes here, only an expanded, warping space-time, similar to Gregor’s flight, but now colored with the depth of new emotional and spiritual dimensions. The labyrinthine melody rolled on and on, reaching ever higher, falling back and reaching again, a melody of melting and surpassing tenderness, sweeping up in its wake the mists of the sublime — that world so far beyond perceptual or imaginative grasp, that our sense of its beauty is deeply mixed with dread. Alarming and reassuring both, it sweeps along, in ecstatic prolongation, immensely complicated, dissolving tonal language — and any other — as if God himself were exhuding enharmonics. Complicated, yet beyond complicated, and thus simple: exaltation, transformation, an intoxicating brew of idealism and lust, delirious forces striving to embrace, exchanging the Kingdom of Day for the Kingdom of Night.

Fingers flying, Miss Mozart piloted this extraordinary tone poem back to its unsafe harbor, the Sensuchtsmotiv. The Prelude to Tristan and Isolde sank down to its embers.

“After such love, why is there still longing?” Lindhorst whispered, tears in his eyes. Miss Mozart turned quietly to the very last pages of the piano score, and in hushed tones, began Isolde’s song of Love’s triumph over Death. “Mild und leise,” Gregor knew the words, “wie er lächelt, wie das Auge hold eröffnet…” She sang beautifully, as extraordinarily well as she played, and not having to overcome an orchestra, she was able to evoke the most delicate nuances of emotion and inflection as Isolde gazes upon her lover, transforming his death into eternal, living, life. In the intimate murmurings of the first serene phrases, slowly rising through unbelievable ascending passages of modulating sequences, wave upon wave, lyrical, rhapsodic, ecstatic, to climactic heights of passion and transfiguration, Isolde makes her decision to die, to melt with Tristan into ultimate ground of being, to leave behind the torment of the finite doomed to infinite yearning. Together they will be at home in the vast realm of unbounded night, borne on high amidst the stars, and then down, down, to where there is no down

In dem wogenden Schwall,

in dem tönenden Schall,

in des Welt-Atems

wehendem All —

ertrinken,

versinken —

unbewußt —

höchste Lust!Release! Death powerless against the Inextinguishable — love’s vast, immeasurable redemption. Yet even here, after this inspired surging of metaphysical perception, even here, in the midst of yes, even here, appear the ineffable harmonies of the Sehnsuchtsmotiv, longing beyond longing, even in final exhalation — longing. Then silence. Profound silence.

[Marc Estrin is a writer and activist, living in Burlington, Vermont. His novels, Insect Dreams, The Half Life of Gregor Samsa, The Education of Arnold Hitler, Golem Song, and The Lamentations of Julius Marantz have won critical acclaim. His memoir, Rehearsing With Gods: Photographs and Essays on the Bread & Puppet Theater (with Ron Simon, photographer) won a 2004 theater book of the year award. He is currently working on a novel about the dead Tchaikovsky.]