Working with the warlords:

Afghanistan and the heroin trade

The U.S. used the international heroin network to serve its geopolitical aims in Afghanistan and elsewhere.

By Sherman DeBrosse / The Rag Blog / May 24, 2010

When George W. Bush and Tony Blair decided to first attack Afghanistan, one consideration was bringing enough stability to run a pipeline down through the country to Pakistan. One wonders if Blair and Bush gave any thought to the heroin trade when they decided to attack the Taliban.

Between 1991 and 2003, about 60 tons of heroin from Afghanistan went to wholesalers along the Volga and in the Urals Districts of Russia. Who knows how much went to the rest of Russia. Northern Afghanistan is the bridgehead for moving drugs into Russia. Far more Afghan heroin went to Europe, the largest single consumer of heroin.

Drugs and banks

In June, 2003, U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan estimated that the international drug trade was worth between $500 billion and $1 trillion a year. The banks that launder this money have a strong incentive to see that the drug trade continues. The Independent reported on February 28, 2004, that, in cash terms, narcotics ranked third in world trade, following oil and arms. Drugs are particularly important because they constitute a form of currency vital to the underworld, international crime, and intelligence agencies.

Making this point could mislead readers into thinking that a high wall separates legitimate and illegitimate transactions. Today, business transactions have become so complex that many so-called legitimate businesses have found it necessary to deal with international criminal organizations and to use their currency of choice, drugs. All too often it is very hard to distinguish between government intelligence agencies and the criminal elements they must cooperate with, and the welfare of some politicians also depends upon the free flow of drugs. Heroin constitutes but one part of that trade.

By then between 80 and 90% of the world’s heroin was coming from Afghanistan. In 2007, the country produced 8,200 tons of opium poppies. The U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime estimates that the Taliban earns from $90 to $400 million from drugs. Most experts place the figure at $125 billion and add that this includes taxes it imposes upon chemicals used to process opium.

The whole country’s annual drug take is somewhere between $2.8 and $3.4 billion. Much of that money goes to line the pockets of Afghan police and officials. A 2008 U.S. Senate report put the value of the transnational sales of all Afghan opiates at between $400 and 500 billion in street value. Some of that found its way to western chemical companies via doubtful routes. Of that amount, about $70 billion is heroin. Up to 10% of the heroin money moves through an informal banking system called hawala. The rest is laundered through Western banks.

Some financial analysts claim that the hundreds of billions in narco-dollars held by huge financial institutions provided the liquidity that made it possible to pull the world back from the potential wreckage of its financial system.

Antonio Maria Costa of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime said, “Drugs money worth billions of dollars kept the financial system afloat at the height of the global crisis.” Costa added, “In many instances, the money from drugs was the only liquid investment capital. In the second half of 2008, liquidity was the banking system’s main problem and hence liquid capital became an important factor.”

Afghanistan’s poppies are enormously important in today’s world, but it is difficult to sort out how drugs have influenced U.S. policy there.

Fighting the Soviets in Afghanistan

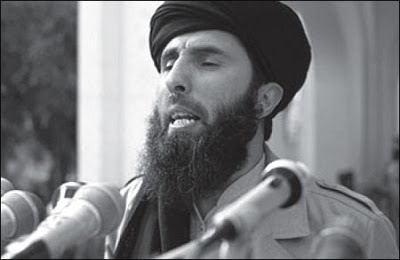

In the 1980s, the C.I.A. helped drug lords become mujahidin leaders. One was Gulbuddin Hekmatya who dominated the local drug trade and became the world’s most important heroin trafficker. Of course, these leaders were encouraged to finance their insurgency through drug sales. With the blessing of the Americans, the drug lords ordered the peasants to raise many poppies. The drug barons were also encouraged to spread heroin to the Russian forces, and this effort was largely successful. Within two years, Afghanistan was the world’s main heroin producer.

Drugs moved from the drug lords to Soviet troops with the help of reputed Russian crime figures such as Vladimir Filin and Aleksei Likhvintsev. They were part of what Russians call “OPS,” an organized crime society. According to Indian observer Theruvath Raman, the C.I.A. controlled this flow.

Since then, massive quantities of heroin have made their way into Russia with the help of an international drug network and likely successor to the BCCI that includes the Russian mafia and Islamic extremists there. Drug addiction there is now as serious as the alcohol problem.

While attempting to combat Islamic extremists in the Middle East, the U.S. was probably working with elements of the Hizb ut-Tahrir al-Islami in Russia. It is a “liberation army” intent upon creating an Islamic caliphate in Central Asia. More recently, it appears that elements in the Russian government and military are sharing business with the narco-barons and bringing some order to the trade by squeezing out the ethnic criminal/drug groups.

A worldwide drugs/arms network takes form

The Russian mafia soon became a major player in moving drugs and arms throughout the world. Many of the arms came from the arsenals of the collapsed Soviet Union that were not located on Russian territory. Some of the leaders in this criminal underground were former intelligence officers, and some of them are highly educated and even respected scholars.

These Russians are the most visible element in a worldwide network that seems to control the movement of drugs in most places, other than the route from Burma to South China. There is much speculation about the extent of U.S. cooperation with this network, and especially its Russian members.

In 1994, the U.S. began shipping arms into Angola through Victor Bout of the OPS, whom the U.S. later employed in Iraq, and is now seeking to arrest. The overthrow of the Ceaucescu regime in Romania and the fall of Shevardnadze in Georgia also involved cooperation with the network. It is possible that the “tulip revolution” in Kyrgyzstan was another joint project. Far West, LLC, an arm of the Russian mob that supposedly specializes in intelligence consulting, moved into Kyrgyzstan after the fall of Askar Akayev, and heroin traffic through that land soon trebled.

Whatever U.S. and Western involvement there was in these nasty activities was masked by various cut-outs. As the Wall Street Journal reported in respect to Georgia, that was work of “a raft of non-government organizations… supported by American and other foundations.” One of the officers of Far West has said that an unnamed American firm had invested in it. Far West has done business with Kellogg, Brown and Root (KBR Halliburton), and Diligence Iraq LLC, a private military firm considered a CIA. spin-off. It is tied to Diligence Middle East, which has links to New Bridge Strategies, which is linked to Neil Bush.

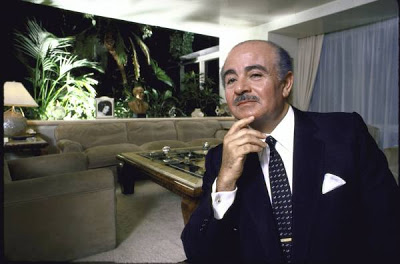

It is known that representatives of the drug network and people close to the CIA met in 1999 under the aegis of Adnan Khashoggi at Beaulieu, France. He has been a CIA asset since the 1960s when he was passing Lockheed money to Saudi officials. One topic at the meeting must have been affairs in the former Yugoslavia, where Kosovo was becoming a major drug entrepot.

Without the knowledge of their defense ministry, Russian paratroopers on June 11, 1999, seized the Slatina airport, giving Russia a base in Kosovo. This was an instance in which the U.S. and the Russian narco-barons were not on the same page. Wesley Clark ordered General Sir Mike Jackson to oust the Russians, but the Brit declined to “start World War Three for him.”

The Russians remained there until 2003, when they shifted their main platform for the export of drugs to Novorossiysk on the Black Sea. That port and St. Petersburg are used to export cocaine brought in from Columbia.

The U.S. and the Caucuses

The Caspian area in 1999 was estimated to have a reserve of 200 billion barrels of black gold or oil. Two years later, it appeared that the reserve was about one tenth that amount.

In December, 1999, the United States again began to play a major role in Turcic, in Central Asia. It sent representatives to a meeting in Azerbaijan where arrangements were made to train mujahedeen from the Caucases and Central/South Asia and also Arabs to assist Chechen rebels. U.S. “private security companies” were used to evade the international embargo against helping the Chechen rebels.

The thinking was that higher levels of violence would dissuade Western investors from making oil deals with Russia. The U.S. was promoting the Baku-Tblisi-Ceyhan pipeline to get oil from the Caspian Basin to the Mediterranean. James Baker III, Adnan Khashoggi, and Lord Mc Alpine had created a Caucasian Common Market to serve this effort. It is administering $3 billion in United States development funds for infrastructure projects in the area. The Bush administration spent $11 in Georgia to train a pipeline protection battalion.

The US intervenes in Afghanistan

The Taliban took over the Afghan drug trade in 1994, with the CIA’s consent, and they seized power in 1996. Relations between the Taliban and the U.S. soured, and in July, 2000, the Taliban moved to end poppy cultivation, calling it un-Islamic. Of course, they were probably doing this to put pressure on the West. The long-term consequences of this currency contraction could have dealt a serious blow to Western financial systems.

Drying up that crop deprived Western banks of billions in new deposits. At that time, Afghanistan produced two-thirds of the world’s heroin, and the absence of new narco-dollars could damage the finanCIAl system. Le Monde and the IMF estimated that about $300 billion in Afghan heroin money had been making its way to Wall Street. Narco-dollars provided needed liquidity to the American and Western financial markets.

The Taliban decision also hurt the Pakistani intelligence service, the ISI. Ironically, the ban also made Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda, major drug operators, far less valuable to the Pakistani spooks. About 60% of Pakistan’s GDP also came from drugs, and the Taliban’s move was a serious blow to its neighbor.

Of course, the Taliban also alienated the Afghan drug lords when they dried up 97% of the opium poppy crop. Banning the drug trade alienated Afghan drug lords, many of whom were in the Northern Alliance. In 2001, the United States began reestablishing close ties with Afghan drug lords, perhaps as preparation for making war in that country.

Drug trafficker Ahmad Shah Massoud became very important to American planners because his guerrilla attacks on the Taliban were often successful. Haji Zaman, “Mr. Ten Percent,” another drug lord, was another important American ally then. He fled to Dijon, France, when the Taliban seized Jalalabad, and the U.S. and British representatives persuaded him to return to Afghanistan.

With the help of Afghan and Pakistani drug lords, Hamid Karzai, a former Unocal employee, gathered support in Pashtun areas. The U.S. seems to have turned a blind eye to the heroin reserves and refineries kept maintained by these people.

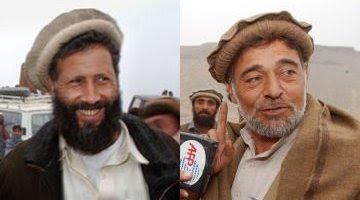

General Tommy Franks gave drug barons Hazrat Ali and Haji Zaman the job of trapping and bringing in Osama bin Laden, who was known to be at Tora Bora. They moved very slowly, not attacking until the bombing had stopped four days before. There was plenty of time for Osama to escape and leave behind a rear guard.

The intelligence chief of Eastern Shura, Pir Baksh Bardiwal, had warned that it was a great mistake to use the two drug lords. They had no interest in seeing the power of Kabul extend to their operations Nangahar Province. U.S. journalist Philip Smucker heard that one of Hazrat Ali’s low level commanders, Ilyas Khel, provided an escort for Bin Laden and showed the Arabs how to escape.

Afghan war lords and poppies

The successful war restored to power brutal war lords whose rule was worse than that of the Taliban. The U.S. military presence in Afghanistan was sharply diminished, and the Bush administration spent very little on nation-building and development. Afghan poppy growing mushroomed, and very little was done about it.

There was talk about eradicating the poppy crop, but some in Washington said that such a step would destabilize the regime in Pakistan. In 2002, a former Indian official offered another reason why the Americans could not move against the Afghan poppy crop:

…this marked lack of success in the heroin front is due to the fact that the Central Intelligence Agency ( CIA) of the USA, which encouraged these heroin barons during the Afghan war of the 1980s in order to spread heroin-addiction amongst the Soviet troops, is now using them in its search for bin Laden and other surviving leaders of the Al Qaeda.

The country produces 8,250 metric tons of opium poppies every year, and and it is moved by trucks by refineries. If the trucks were stopped, the refineries would go out of business. There are reports that India supports some refineries which generate money for insurgents in Pakistan. The Israelis did the same for insurgents in Iran.

Authorities in neighboring Tajikistan complain that neither the U.S. nor NATO is moving against the Afghan drug lords. The Tajikistan Drug Control Agency’s Avaz Yuldashov noted: “Our intelligence shows there are 400 labs making heroin there, and 80 of them are situated along our border.” He added that drug money from Afghanistan pays for international terrorism. In addition there are many labs in Pakistan to process Afghan poppies. The drugs are then shipped out of Karachi. Most Afghan drugs end up in Turkey, a NATO member, from whence they are moved to Europe.

Some drug lords are allied with President Karzai, and his half-brother Ahmed Wali Karzai, head of the Kandahar provincial council, has been accused of being in the drug trade. It is said that he ships drugs to Iran. If so, he would have to pay some Taliban tolls to keep the product moving.

Those drugs could be used in Iran, but much of that cargo goes to Russia via Iran. Much has been written about warlords tied to Wali benefiting from a $2.16 billion U.S. contract for trucking services. Current and former intelligence officials tell reporters that Wali has been on the C.I.A. payroll for eight years.

Has the U.S. been dealing heroin?

It is difficult to establish whether the U.S is benefiting directly and financially from the Afghan drug trade. Political scientist Vladimir Filin, once head of Far West, told an interviewer that this is the case. He noted that, “They control Bagram airfield from where the Air Force transport planes fly to a U.S. base in Germany.” From there, heroin goes to “other U.S. bases and installations in Europe.” Much is shipped to Kosovo where the Kosovo Albanian mafia move it it “back to Germany and other EU countries.”

In time, he predicted, U.S. drug centers will be shifted to Pozan, Poland, Romania, and Bulgaria because those host countries tolerate high levels of corruption. He estimated that America was moving between 15 and 20 tons into Europe per year, That is not a huge share of the world drug trade. However, other Russian observers place the tonnage at a much higher level and offer many more details about how the heroin is taken out and where it goes . General Mahmut Gareev, who commanded Soviet troops in Afghanistan, said:

Americans themselves admit that drugs are often transported out of Afghanistan on American planes. Drug trafficking in Afghanistan brings them about 50 billion dollars a year — which fully covers the expenses tied to keeping their troops there. Essentially, they are not going to interfere and stop the production of drugs.

General Khodaidad, the Afghan counternarcotics minister, also said the Americans and British are stockpiling the opium poppies in the provinces they control, and he added that NATO forces often tax the production. Former F.B.I. translator Sybel Edmonds told Congress that some military planes were used to move the heroin, but she was twice silenced by the Bush administration through the state secret privilege.

Dennis Dayle, a former DEA. agent said:

In my 30-year history in the Drug Enforcement Administration and related agencies, the major targets of my investigations almost invariably turned out to be working for the C.I.A.

No one wants to believe that our government is deeply involved in the narcotics trade. Perhaps none of these sources can be believed. However, we do know that the U.S. was selling drugs to its troops in Vietnam and moving some drugs out of Southeast Asia then. At the very least, it was also protecting Nicaraguan Contras who moved drugs into the U.S. to pay for weapons. Maybe there is a pattern here. Conversely, there seems to be a long-standing pattern of mainstream media not looking into these matters.

Two problems

The U.S. used the international heroin network to serve its geopolitical aims in Afghanistan and elsewhere. Peter Dale Scott, upon whose solid work this piece is partially based, has suggested that the drug/arms network may have grown so powerful that it is no longer just a tool to be used by the U.S. government. It may have its own agenda and the ability to bend U.S. policy to serve its objectives.

The present situation is very different from the days when the U.S. relied on private firms run by retired U.S. officials and politicians to carry out illicit weapons transactions or help the Nicaraguan Contras move drugs.

A second problem is that American aims in Afghanistan may have conflicted with those of the local drug lords. The drug industry thrives where state power is weak, where nothing can be done about peasants growing poppies, and the state cannot move against refineries and stockpiles.

The United States claimed that it wanted to expand state power and to bring order and stability to Afghanistan. Order was also needed if headway was to be made on the TAPI pipeline that was critical to U.S.-owned electrical facilities in India. Possibly, American planners thought that these conflicting interests could be reconciled. Clearly, the drug barons thought otherwise. At this moment, it appears that the TAPI venture could be doomed.

[Sherman DeBrosse is a regular contributor to The Rag Blog. A retired history professor, he also blogs at Sherm Says and on DailyKos.]