‘En un lugar de la Mancha…’

On reading Cervantes aloud in Madrid

By Tom Miller / The Rag Blog / May 14, 2010

All together now: “En un lugar de la Mancha, de cuyo nombre no quiero acordarme, no ha mucho tiempo que vivía un hidalgo de los de lanza en astillero, adarga antigua, rocín flaco y galgo corredor.”

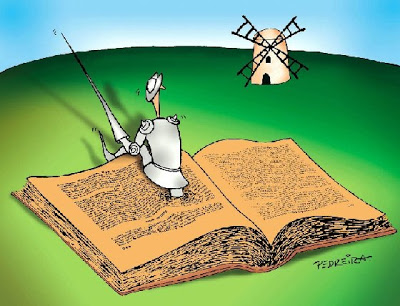

If you don’t recognize those 33 words, go to the back of the class. The rest of you can identify the opening line from Don Quixote de la Mancha, the world’s best-loved and most translated novel. Since its initial publication in the early 17th century (in two parts; 1605 and 1615) the Quixote has been considered the first modern novel and its author Miguel de Cervantes has come to symbolize the Spanish language. If you grew up in a Spanish-speaking country you likely can recite those words in your sleep.

Ground zero for Cervantes, of course, is Madrid, where he lived off and on, and died April 23, 1616. William Shakespeare, who symbolized another language, died April 23, 1616 as well. In those days Spain followed one calendar while England used another, so although Miguel de Cervantes’ and William Shakespeare died the same date, they did not die the same day. (Or, as I explain to friends in Tucson, one followed the calendar from El Charro, and the other, from Mi Nidito.)

April 23 has evolved into El Día del Libro in Spain, a very literary day on which the King awards the annual Cervantes Prize for outstanding work in the Spanish language, and kiosks and big displays of books line the streets of Madrid, Barcelona, and elsewhere. (In Barcelona, it’s also Sant Jordi day, which, in addition to celebrating books, includes giving a rose to a lover or someone you’d like to be a lover. Books and lovers; I ask you, could there be a more fertile combination?)

Madrid’s main activity takes place in the Circulo be Bellas Artes (CBA), a huge building on a broad mid-town boulevard with galleries, rooms for workshops, theater, meetings, and exhibits, as well as a nicely stocked bookstore named for the poet Antonio Machado. And it’s here every year that the Lectura Continuada, the marathon reading, of the thousand-page Don Quixote takes place.

The first reader, always, is the winner of the Cervantes Prize, in this case, the Mexican poet José Emilio Pacheco. He’s followed by politicos, actors, high-ranking cultural bureaucrats, and the like. Each reader gets a paragraph or two at most. The CBA has a high-tech approach to the Quixote, and arranged for teleconferencing from readers in cities throughout Africa, the Americas, and Asia. And, it was web-streamed, so from whatever distance, if you cranked up your computer during the marathon, you could have heard more than a thousand readers, including… me.

A month earlier I made an international call to the phone number listed on the CBA web site, but the nine-hour time difference made that window of opportunity difficult to jump through. So shortly after I arrived in Spain I went to the CBA building and found the registration table. “When would like to read?” a woman asked ingenuously. “We have a lot of openings at this point.” I chose 6 p.m. the first day simply out of convenience. Because of the ebb and flow, you never knew your precise passage until 30 seconds before you read. For those of us for whom os and vuestra are not part of our normal Spanish, this could be a bit intimidating.

Except for the stage, the main room was always dark so the whole process could be video’d. A big screen showed clips from the many film versions of Don Quixote. Great stuff! And you deaf readers, imagine Don Quixote in sign language! These signers were as much actors as translators, taking on the roles of el Quixote and Sancho Panza and the whole cast of characters. To add to the literary carnival a few excerpts were acted out by local theater groups.

The process ran smoothly. Like every other reader, I checked in at a table outside the main room at my appointed time and got a ticket. I was then directed to a line on the side of the auditorium, where, when I reached the front, someone verified my name with a list. While the person three ahead of me was reading out loud from the podium, the fellow two ahead of me was sitting with the ringmistress, as I called her, following the passage on stage so he’d know where his own segment began, while the chica directly in front of me was at the front table on stage signing paperwork.

At one point I got the nod and proceeded to the front table where I signed my name and gave my employment (“¿A que te dedicas?” the fellow whispered.) A minute later I moved up to the second-to-top rung, sitting next to the ringmistress following along with the reader before me.

The previous weekend I spent in Argamasilla de Alba, a small village in La Mancha that Cervantes was known to have visited and said to have been imprisoned in for a spell. Unbeknownst to me A de A was having its own Lectura Continuada, and the cervantistas invited me to take part. The town was so small they only had enough people to read the novel’s first part, and for that students from local public schools took turns. Unlike in Madrid, these people could show me my section ahead of time. I found it in the English translation always by my side, and eventually was called to the stage which really wasn’t a stage, more like a table covered by a big cloth in the front of a big room.

I said, “Para mostrar el alcance internacional de Cervantes y el Quixote, voy a leer mi fragmento en otro idioma.” (One should never be too far from one’s own copy of el Quixote.) And with that, I read the occasionally testy conversation in Part One, chapter twelve, between Don Quixote the shepherd Pedro about the late student — shepherd Grisótomo.

The ringmistress in Madrid nodded me over to the chair next to hers as the previous participant stood at the lectern. We followed the passage being read on a large-type edition — the exact same edition on the lectern. After just a few sentences from the reader right before me, the ringmistress said “Gracias,” and motioned me up. Her “Gracias” was sort of like the hook of an exceptionally bad performance, except in this case it was simply used to hurry the reading along. Move along little dogies.

I was temporarily disoriented and the ringmistress had to walk over to point out where I should start. The sign language translator, with whom I’d been chatting in the lobby, gave me a supportive smile. We were in Part One, chapter 21, when the good don and Sancho are having one of their near-quarrels. In all I read 77 words. As I left the stage there was the obligatory smattering of applause that followed every reader.

Afterward I stood by myself in the back listening to the readers who followed me. One of them, a South American, came up, and in a low voice, said: “Your accent. Are you from Germany?”

[Tom Miller’s most recent book is Revenge of the Saguaro: Offbeat Travels Through America’s Southwest. He is working on Don Quixote’s Trail — Through the Wilds and Windmills of the World’s Best Loved Novel. His web site is www.tommillerbooks.com.]

Also see:

- Tom Miller : When Jerry Rubin Came to Tucson / The Rag Blog / January 25, 2010