Colombia: Don Mario’s war

By his own account, [his] victims number somewhere around 9,000, but hey, who’s counting? He murdered so many Colombians that he can only guess in round numbers.

By Marion Delgado / The Rag Blog / April 20

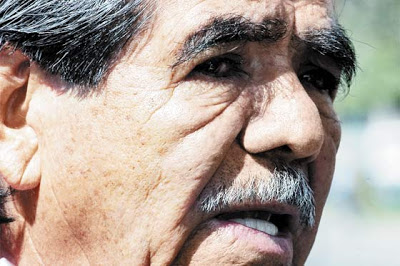

AT LARGE IN COLOMBIA — “Don Mario” was on TV during the week of March 21-26. He was making another appearance before Colombia’s Peace and Justice Commission. After Carlos Castaño, Don Mario (nee Daniel Rendon Herrera), is as big a “Mister Big” in the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC; United Self-Defense Groups of Colombia) as they come. At one time he controlled most of the cocaine transportation out of Colombia.

The Don swaggered across the TV’s flat screen and into the Commission’s hearing room. At 44 years, he looked good in his Armani suit and of course, his right sleeve was pulled up a little to display his Rolex watch. It is rumored that he wears a new one every day. He stacked 200 million Colombian pesos on the table, paused, turned to smile at the TV cameras, and sat down. La Plata was his down payment on restitution he is required to make to the families of his victims.

By his own account, those victims number somewhere around 9,000, but hey, who’s counting? He murdered so many Colombians that he can only guess in round numbers.

I have mentioned him several times in my dispatches over the last few months, but he was always a bit of a mythical figure. A leader of one of the most powerful AUC blocs, the Urabá or Urabeños, his name came up again and again in my research. The televised hearings, or more appropriately, “The Don Mario Show,” made me want to find out more about who he is and what he had done. I had a good source, Don Mario himself.

The Colombian government put a price on his head, five billion pesos (two and a half million U.S. dollars). Don Mario in turn offered a $1,000 reward for every killed policeman. While his AUC companeros were demobilized, or at least pretended to be, the Don stayed on the run. He was captured in April 2009. But Don Mario, legendary paramilitar, wasn’t finished.

He applied for the amnesty offered under the Peace and Justice Act. If he would make a full “confession” of his crimes, and make restitution to his victims, he would avoid prison in Colombia and be protected from extradition to the U.S. The U.S. Departments of Justice and State have twice requested his extradition, and have been twice refused by the Supreme Court of Colombia.

Don Mario began to tell his story in early November 2009 and, over five- and six-day-long weeks, has continued to confess through mid-March 2010. There are hundreds of pages of testimony, with no English translation yet. It’s a book, bigger than a book. It’s way too big to blog, so I have extracted his account of one time, in one place, with all the players, that tells the story of one part of Don Mario’s war. It’s his story, but some of it I got from Human Rights Watch, NACLA, and other NGO’s, from the UN Commission on Human Rights, and some from the stories filed with the Commission by the unwilling participants, the Colombian people. It was their war more than it was Don Mario’s

The time and place

In little more than a few months between late 2003 and early 2004, about 3,000 people, including civilians and combatants, were killed in Casanare, a Department, or state, in eastern Colombia rich with oilfields across rolling, fertile plains.

Two paramilitary factions, supposedly created to combat rebel guerrillas, fought each other for control of drug trafficking, oil royalties, and thousands of hectares of land in Casanare in a paranoiac, hellish war that left thousands of victims, a war still very much a secret even in Colombia.

In this chilling war of deceit, paranoia, and greed, even children paid the ultimate price.

Martin Llanos’ war in los llanos (plains) of Casanare

Very little is known of the war in Casanare. Several different factions of paramilitaries clashed not only with Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia — Ejército del Pueblo (FARC or FARC-EP; Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia — Peoples Army) rebels, but among themselves.

Many paramilitaries who committed crimes in this Department never participated in the process of demobilization of the AUC. Many of the protagonists have died, or are fugitives.

Drug boss and paramilitary chief Hector Buitrago, alias “Martin Llanos,” refused to demobilize and is still wanted in connection with crimes committed by his group. Miguel Arroyave, alias “Archangel,” was later killed by his own men. Pedro Oliverio Guerrero Castillo, alias “Cuchillo,” went into hiding but was captured in March 2010.

The plains inhabitants, the Casanareños, witnessed a massacre in which even children were killed, as hundreds of civilians and paramilitaries clashed with each other.

In his testimony, as part of the Peace and Justice Law, Don Mario said the man responsible for the war was emerald trader Victor Carranza; however, Carranza’s motives for such scheming remain obscure.

“Carranza spoke with Miguel (Arroyave) about Martin (Llanos), and from there I realized that he was using Miguel to alienate Martin. I think he did the same with Martin,” said Don Mario. He said Carranza sowed discord between the two paramilitary leaders, telling each one that the other wanted to kill him.

The war was costly, not only for the population it ravaged, but on the pocketbooks of the combatants. According to Don Mario, within a month the Centaurs Bloc of the AUC spent about U.S. $7 million for the war. On one day of fighting, his men used 100,000 rounds of ammunition at a cost of U.S. $200,000, said the former paramilitary, chief financial officer of the Centaurs until mid-2004.

One combatant said the war with Llanos made Archangel distrust everyone, even his own men. Many were killed on “suspicion” alone.

Few in this region dare speak about the months-long massacre even now. What is agreed is that for decades illegal armed groups had fought for a slice of the pie in Casanare: oil, timber, agriculture, and illicit coca crops.

The back story

The war in Casanare began about mid-1986, when Buitrago/Llanos organized a paramilitary group, the “Buitragueños,” to fight guerrillas. The group operated in Casanare, Meta, and part of the Ariari subregion, which irked Pirabán Manuel de Jesus, aka “Pirata,” and Guerrero/“Cuchillo” of the Centaurs.

One villager knowledgeable of the Buitragueños expansion said that Buitrago/Llanos joined with the Ramirez and Feliciano families, both large landowners, and began setting up cocaine processing labs in Monterrey and Tauramena Aguazul. They also began murdering people by the hundreds. Local cattle ranchers, big supporters of the AUC for protecting their grazing lands, gave the paramilitaries ranches from which to mount their operations.

Besides engaging in counterinsurgency against the guerrillas, Buitrago’s forces intimidated and forced entire villages to become complicit in covering up drug trafficking activities.

“They collected people in the parks, locked down students in their classes, and told people not to leave their houses because of alleged danger of subversive guerrilla activity, but the fact is they wanted people ‘locked away’ so they wouldn’t see the trucks loaded with paramilitaries or with chemicals to process the cocaine. It was all a big lie because the guerrilla presence wasn’t seen in Monterrey,” said a former Casanare municipal official.

The Buitragueños did not limit themselves to fabricating guerrilla threats. After 1995, they began a systematic campaign to seize land with oil fields and to evict farmers from exploration areas.

“From Monterrey to Tauramena Aguazul, they came to farms and cattle ranches. ‘Sign or die,’ they said to landowners regarding deeds and titles. Threats, or worse, were also offered to girls who did not succumb to advances. They were raped or banished if they did not sleep with them,” says a person who lived in the area.

The prosecutor and judges of Villavicencio finally launched a conspiracy investigation against Buitrago/Llanos, resulting in his incarceration. He later escaped.

While Buitrago/Llanos consolidated power south and north of Casanare, the Autodefensas Campesinas del Casanare (ACC), paramilitaries aligned with Carlos Castaño, began to move into parts of Guaviare and Meta Departments.

Castaño, a founder and one-time leader of the AUC who was later killed by his own men, came to Casanare with members of the Autodefensas Campesinas de Córdoba y Urabá (ACCU) and killed over 50 people near Meta in 1997.

The slaughter was supported by the ACC. But soon a feud developed between the Martin Llanos group and the Castaño paramilitaries. This deepened with the slaughter of 11 members of a judicial commission investigating a land dispute in October, 1997. That massacre, ordered by Llanos, offended Castaño.

By this time, Castaño forces had pushed into Casanare and Arauca Departments, clashing with FARC and Ejercito de Liberacion Nacional (ELN; the National Liberation Army) guerrillas.

With Castaño’s entrance into his turf, Llanos began to feel threatened.

The war gets crazier

Ex-fighters said Llanos began to step up extortion, killing farmers to seize land, and exerting political pressure to remain in control of Casanare.

“Llanos was going crazy. He did not allow anyone within 30 feet of him, and if he suspected someone would turn him in, they would be tortured and later assassinated. Several youths were killed and returned to their families in black plastic bags. Dozens of his men were executed like this in Puerto Lopez, on mere suspicion,” said residents who saw the corpses.

Llanos’ paranoia drove him to kill people close to him, such as Victor Feliciano Alfonso; his wife, Martha Nelly Chavez; Juan Manuel Feliciano Chavez; and four other family members in February 2000. Only Victor Francisco Feliciano was left alive; he denied any family ties to drug trafficking.

Llanos began to lose control of the northern department, especially Yopal, where the population was caught in the crossfire.

In April 2001 about 15,000 people protested the violence. Traders, farmers, civilians, and politicians shook off their fear and called for an end to warfare under banners saying, “Our silence fills the graves of the plains with Casanareños.”

However, fighting intensified until an average of 10 people per week were being killed, although police recorded that in the first quarter of 2001 there were “only” 85 murders. Police statistics differ deeply from reports of the Ombudsman, according to whom, between 1997 and the first three months of 2001, there were 31 massacres, of which 12 were in Yopal in the first months of 2001.

During April 2001, 2,404 farmers were also displaced. Still, authorities described Casanare as “a haven of peace.”

In April, 2001, Martin Llanos called forced meetings of ordinary citizens, from taxi drivers to teachers, to try to influence electoral campaigns. In one meeting, 200 teachers came to Monterey, where the paramilitary leader declared, “Those who vote for the Democratic candidates or for Horacio Serpa should assume [there will be] consequences,” said one teacher who attended the meeting, now a refugee in Villavicencio.

“He came in a small helicopter they called ‘the wasp,’ greeted former classmates from the Joint Normal School in Monterrey, recalled their days as students, and even became remorseful. He spoke for about 15 minutes, turned, and left,” said the teacher.

The paramilitaries’ infighting in Casanare also produced divisions within the ACC’s southern and northern factions, the latter commanded by Luis Eduardo Ramirez Vargas, alias “HK”, killed by Bogotá police in December 2005.

The beginning of the end

Miguel Arroyave/“Archangel” shared power in the Centaurs Bloc with Carlos Castaño and his brother Vicente in early 2002. At that same time, Miguel Angel and Victor Manuel Mejia Munera shared power in the Arauca Vencedores Bloc. These groups eventually formed an alliance against Martin Llanos in Meta, Casanare, and Arauca.

Castaño’s forces did not know the terrain and at first took a beating from Llanos’ men.

Videos circulating in Monterrey, recorded by members of the ACC in the area, showed fighting between the two sides in rural areas of Mapiripan. The images revealed rotting bodies, abandoned military equipment, and machine gun crossfire between ragtag groups of terrified youths of African descent, in panicked, leaderless flight.

After these initial defeats, Castaño sent reinforcements from the Centaurs, Central Bolívar (BCB), and St. Martin Blocs, and quickly gained numerical superiority.

Llanos’ forces were reduced to 300. Castaño’s men pushed them north of Casanare.

According to some Monterrey survivors, the Colombian Air Force helped out with bombing raids. A former Centaurs commander said Miguel Arroyave had asked a senior air force officer to help stop Llanos.

Surrounded and demoralized, Llanos dug in near El Tropezón, a few miles from Puerto Lopez. There his forces took a stand until the air force bombings.

Decimated then, Llanos began “recruiting” in the capital districts of Ciudad Bolivar, Soacha, Kennedy, Bosa, and Suba, and in the Morichal district of Villavicencio. His remaining forces took 30 children by force there.

“People had to leave the sidewalks of Caribayona and El Pinal, because they tricked or forced children as young as 12 years old into their ranks,” said the mother of one of those children, who later rescued him from the mountains and fled to another city.

The horror of teenagers inside the ACC

“Those caught crying were killed in front of others. And if someone fell asleep on watch, a worse fate fell upon them,” said the family of another minor arrested in a military action and sent to a reform institution.

Skirmishes between the competing paramilitaries lasted until early 2004. One battle in February that year lasted for five days at Caribayona, near Villanueva. In that confrontation, more than 140 paramilitaries from both sides were killed, and about 20 farmer-soldiers were killed near Villanueva during Archangel’s eventual retreat.

“In the combat zone, superiors asked their troops, some of them children, if they were tired. If they responded affirmatively, they were shot. So were the wounded that arrived in Puerto Lopez and Monterrey. They asked the nurses which paramilitaries had serious wounds. They were rounded up in a single place and then a fighter would toss in a grenade, or they were simply shot,” eyewitnesses testified.

Fighting continued between Villanueva, Monterrey, and Tauramena.

“Finally, Castaño’s men overtook the fighters loyal to Llanos, whom many said had made a pact with the devil. Prisoners were shoved into a corral, given only one meal a day, and every week one was beheaded. There were guys who painted their nails black and lined up to drink the blood of the victims,” said another woman whose daughter lived for a time with one of Llanos’ men.

In July 2004, the Colombian army secured El Tropezón and captured ACC fighters on the outskirts of Monterrey. The crows were fattened on those who fell in this battle.

In a single day in Puerto Lopez, 30 child soldiers died, and in Tauramena 20 others were killed near La Candelaria. Their bodies, pulled by tractors, were cast into the river Metada with their stomachs cut open so they would sink.

Fighting led to displacement of civilians in Las Delicias, El Yari, El Retorno, El Tranquero, and everywhere the forces of Llanos and Castaño met. About 30,000 people were forced to leave La Tronca de la Selva. Many protested because the Army did nothing to stop the violence.

When the end was near, Martin Llanos fled with a guard of 10 men and 70 children from Bogotá, Villavicencio, and around the region. The children were used as human shields to cover the paramilitary leader’s flight.

Days later, on September 26, the Colombian government said in a statement that 79 men of the ACC had been killed. Many fighters surrendered and others were captured, but Llanos, wounded, fled to Ecuador. He then moved on to Brazil, and later to the border between Colombia and Venezuela, from where he still sends threats and warnings of revenge to enemies in Monterrey.

Although hundreds of paramilitary units of the Casanare Centaurs demobilized, they have been replaced by resurgent groups and remnants of the Urabeños, Carlos Castaño’s original bloc that only pretended to demobilize. They now operate side by side, still protecting the cocaine trade, old wars forgotten…but not old war stories.

Don Mario is cleansed

Don Mario, who was paymaster of the Centaur Bloc and “inherited” the leadership when Castaño was murdered, checked his Rolex. He’d had enough storytelling for the day.

Despite his participation in the Casanare wars and the murder of 9,000 Colombians there and elsewhere, he has finished telling all of his stories, paid a paltry sum in restitution, and will now go free.

Marion:

All I can say is thanks. Tremendous journalism… a story whose horror and tragedy is the child of the outrageous drug policies of the U.S. This insanity… that stretches from Bolivia to Columbia to Kabul to Penang to Berlin to Los Angeles, destroying not 9000 but millions of lives along the way… must end.

Again, thanks.

s