The thirty years war:

The United States in Afghanistan

By Harry Targ / The Rag Blog / December 27, 2009

When the Soviet Union sent 85,000 of its troops to Afghanistan in late December 1979 President Carter declared that the United States was forced to return to Cold War military preparedness. But, in fact, the Carter administration had been escalating military commitments and operations throughout 1979, months before the Soviet action.

In a brief televised address two weeks after the Soviet invasion, the President denounced it as “a deliberate effort by a powerful atheistic government to subjugate an independent Islamic people.” He said it threatened “both Iran and Pakistan” and was “a stepping-stone” for the Soviets’ possible control “over much of the world’s oil supplies.”

The President followed his brief condemnation with a lengthy State of the Union address to the American people on January 21, 1980. In it he announced some extraordinary changes in United States foreign policy that constituted a decisive return to Cold War with the Soviet Union.

The changes Carter initiated included the following: reduction of grain sales to the Soviet Union; curtailment of high technology trade with them; postponement of ratification of the SALT II arms control agreement; enlarging strategic forces; beefing up NATO forces; establishing a Caribbean Joint Task Force Headquarters; unleashing the CIA; installing a program of draft registration; and providing more military assistance to Pakistan, South Korea, and Thailand.

Perhaps the most important policy change was the establishment of a 100,000 person military “rapid deployment force” which could be instantly mobilized in crisis situations. And he proclaimed that the Persian Gulf was vital to U.S. security interests and would be protected; this became known as the Carter Doctrine.

All these announced changes were billed by administration spokespersons as a response to the duplicitous Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Ultimately, the Soviets wanted to invade Iran, secure Persian Gulf oil, secure warm water ports, and expand their Asian empire. The U.S., they said, had to respond to this expansion of the Cold War.

But a careful examination of the events of 1979 prior to the Soviet invasion suggests a different timeline and interpretation. In January 1979 the Shah of Iran, the closest of U.S. allies, was toppled in a revolution. Carter’s aides initially had urged him to send troops to Teheran to save our Persian Gulf cop from ouster but the revolution came too fast to save the Shah.

After Iran, in the Caribbean and Central America revolutions occurred in tiny Grenada (March 1979) and historically anti-Communist Nicaragua (July 1979). There was a coup by military reformers in El Salvador (October 1979). In early November 1979 Iranian students took approximately 70 U.S. government representatives hostage.

The administration perceived itself as being threatened by the spread of hostile regimes and movements and the collapse of the vital ally in Iran was deemed the most critical to U.S. interests. As a result of all these crises, Carter began military rearmament, secured new bases, tried to undermine the changes occurring in Nicaragua and El Salvador, and allowed the Shah of Iran to enter the United States in October 1979 for medical treatment.

Inside the Carter administration, foreign policy decision makers feared the collapse of U.S. power around the world. However, they felt the United States could not respond because of the so-called “Vietnam Syndrome.” That is, decision makers believed that most Americans opposed a return to militarism and interventionism.

Then, fortunately for the Carter team, the Soviet Union, fearful of the collapse of an allied regime in Kabul and increasingly seeing itself as encircled by China in the East and a beefed up NATO in the West, sent troops into Afghanistan. The Soviet Union fell into a trap set by the Carter Administration.

What was the nature of this trap? Well, Jimmy Carter’s National Security Advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski, in an interview given to the French newspaper Le Nouvel Observateur in January 1998, said that official CIA accounts which say the United States began to support rebels in Afghanistan after the Soviet invasion were lies. In fact, he said, “…it was July 3, 1979 that President Carter signed the first directive for secret aid to the opponents of the pro-Soviet regime in Kabul.” The National Security advisor said he wrote the President “…that in my opinion this aid was going to induce a Soviet military intervention.”

Brzezinski told Carter that the Soviets would probably intervene in Afghanistan if we funded rebels and that they, the Soviets, would then be buried in their own Vietnam. In retrospect, he said, the Soviet incursion led to the collapse of the Soviet Union and its “empire.” He suggested that the rise of Islamic fundamentalism was of minor concern compared to the threat of international communism.

Reflecting back 30 years, the following conclusions seem justified. First the United States returned to an aggressive Cold War policy not after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan but before it.

Second, President Carter announced a broad array of aggressive policies toward the Soviet Union after the Soviet invasion but these were in place or in the process of development before the Soviet moves of December 1979.

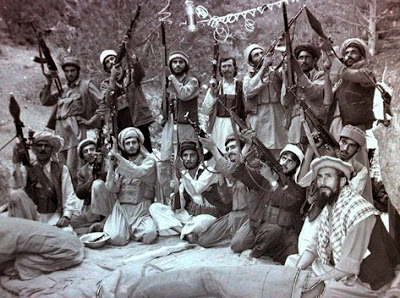

Third, the United States began funding the various fundamentalist groups to fight against the secular and modernizing regime in Kabul before the Soviets sent troops. And that led subsequently, as the Center for Defense Information estimated, to the United States funneling $2 billion to rebel forces in Afghanistan in the 1980s.

Fourth, the war on the pro-Soviet regime in Kabul destroyed efforts to modernize the tradition-bound country. Women, who had become active participants in public life and the economy in the 1980s lost control of their lives after the pro-Soviet regime collapsed. In general, an estimated one million Afghans died in the 1980s from war and repression and some five million fled the country.

We know about what happened after the troubled 1980s in Afghanistan. The Soviet troops withdrew. After a time, the secular regime in Kabul was ousted from power. Competing fundamentalist militias vied for control of the state. The Taliban consolidated their power by 1996. Then the United States launched its public war on Afghanistan in October 2001. But, the record suggests, the United States initiated its war on the country as far back as July 1979.

The pain and suffering of the peoples of Afghanistan has a long history before and since the United States intervened in their political lives in 1979. Many outside powers share responsibility for their plight. But today’s situation directly relates to the covert war the United States encouraged and funded from the summer of 1979.

[Harry Tarq is a professor in American Studies who lives in West Lafayette, Indiana. He blogs at Diary of a Heartland Radical, where this article also appears.]

Let me get this straight…you’re saying it was the fault of the United States that the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979?

Gedaliya, it’s not 100% black and white, like you seem to be trying to reduce it to, but Carter’s NSA Brezinski’s specific and literal goal was to embroil the Soviet Union in their own “Vietnam”, namely Afghanistan. Carter began heavily arming the Mujahadeen almost six months prior to the Soviet invasion, so you do the math.

Your attempt to charactrize the author’s description of the complex geopolitics of Brezinski’s “Grand Chessboard” as “the fault of the United States” is a pretty lame attempt to set up a straw man dissidence here. But the Rag Blog’s readers see through such attempted charades, and yours will get nowhere with any of them.

First you say, “it’s not 100% black or white,” and then you say “Carter began heavily arming the Mujahadeen almost six months prior to the Soviet invasion, so you do the math.”

Either the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan to thwart a US-backed armed insurgency on its southern border, or it invaded Afghanistan as part of its decades-old program of imperial expansion.

You contend it was the former, I contend it was the latter. My guess is that most scholars and political scientists support my point-of-view, while most conspiracy-obsessed one-note johnnys support yours.

You do the math.

I appreciate the interest expressed in my essay. I agree with Anonymous’s interpretation of United States foreign polocy goals. Several points seem relevant to us today: 1)the United States has been actively involved in Afghanistan at least since 1979,

not just since October, 2001. 2)US involvement preceeded the Soviet invasion of the country by six months; 3)US covert operations occurred in the context of multiple threats to US global dominance, beginning significantly with the collapse of our vital ally, the Shah of Iran. 4)While Soviet military operations were brutal in the 1980s, the US was significantly supporting the other side, which consisted of seven major Islamic fundamentalist groups. These, of course, included such luminaries as Osama bin Laden.

5)We should not forget that in the midst of Soviet/Kabul violence and civil war, the status of women in the country improved dramatically.

6)For those who are reminded of Vietnam, the U.S. supported the French and anti-Communist Vietnamese in the 1950s before the dramatic escalation of the US war in the 1960s.

All this should be part of our calculus of US foreign policy in 2009 and I agree with those who say we must withdraw from Afghanistan as soon as possible.

What a strange argument. First, you blame the United States for the invasion of Afghanistan, and then you defend the Soviet invasion and occupation because the status of women improved throughout its duration.

If this is so, one would expect you to defend the US provocation, since the result of its application was a general improvement in Afghan social conditions.

I must confess your argument leaves me somewhat confused.