Today’s fanatic, tomorrow’s saint

It’s popular to think that the world gets changed by nice people, but the lives of activists past and present tell us otherwise

By Rebecca Solnit / November 30, 2009

The question: Is fanaticism always wrong?

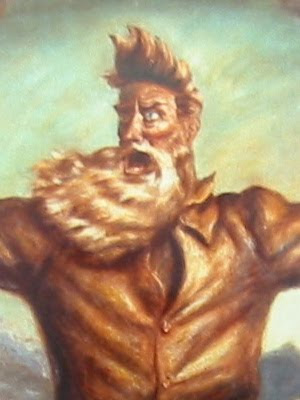

John Brown, who was hanged 150 years ago this week, was a religious terrorist. Driven by his unshakable belief in God and his own righteousness, he killed civilians, went on suicide missions, and fomented one of the most terrible and destructive wars in history. Yet his cause was undoubtedly good. Everything he did, he did to abolish slavery; and in the end, he triumphed. The Union armies, singing “John Brown’s body lies a mouldering in his grave,” marched on, together with his soul, through the confederacy until it was crushed and the slaves freed. Looking back at his life and death we are left with an awful question: is fanaticism always wrong?

By fanaticism we usually mean two things. One is that someone is dedicated in the extreme to their cause, belief, or agenda, willing to live and die and maybe kill for it, as John Brown was. The other is that the cause, belief or agenda is not ours, and in 1859 John Brown’s beliefs were not those of most Americans.

No one calls himself or herself a fanatic. It’s what you call people who are weird or threatening, extremists in the defence of something other than your own worldview. I’ve been around activists all my adult life, and though it’s popular to think the world gets changed by delightful people, a lot of the saints and agents of change are obsessive, intransigent, unreasonable, and demanding, of themselves and of us. That’s what it generally takes to change the world.

Gandhi knew this when he said, “First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.” Conventional people give up when they laugh at you. Timid people back off when they fight you. They don’t win, and neither do those who prize ease and security. The prize is for those who risk and persevere.

That slavery was an intolerable evil is something slaves have tended to believe all along; a few free men caught up with them in England in the 1770s, as Adam Hochschild’s wonderful history Bury the Chains relates, and that handful of Quakers and dissenters persevered until they won, half a century later. I am not so sure about John Brown’s means, or that his actions were necessary to start a war that was already brewing, but I am sure that slavery needed to be abolished, and that his general ends were good.

The really interesting thing is that in 1839 to be against slavery in the U.S. was a disruptive, extreme position, often seen as an attack on property rights rather than a defence of human rights. Half a century later we held those truths to be self-evident that no one should own anyone else. (Except husbands owning wives, but that’s another story that got revised in the 1970s and 1980s when things like domestic violence came to be taken seriously by the legal system of many countries. Sort of.)

Lincoln called John Brown a “misguided fanatic.” Thoreau wrote a defence of him in which he remarked, “The only government that I recognise — and it matters not how few are at the head of it, or how small its army — is that power that establishes justice in the land.” Some 13 years before Brown’s bloody raid on Harper’s Ferry, Thoreau went to jail, in a quiet, half-comic way, to protest slavery and the U.S.’s territorial war on Mexico.

I’m writing this the evening before the global day of climate action, on the 10th anniversary of the Seattle WTO uprisings. I was in Seattle when the mainstream considered us nuts to think corporate globalisation was a bad idea; that perspective is mainstream now; and I can see the world waking up and shifting its sense of what we need to do about climate change. A quick online search reveals quite a lot of people have been called “climate-change fanatics,” mostly for believing the change is real and it requires some fairly profound responses. But the baseline of belief is shifting, thanks to the dedicated and unreasonable among us.

Fanatic is a troublesome word. I’ve written a book about disasters in which I propose throwing out the words panic and looting, because they’re incendiary terms more often used to misrepresent and justify authoritarian response than to describe reality on the ground. Maybe fanaticism is another such term, since my hero is your fanatic, and yesterday’s fanatic is so often tomorrow’s saint. Maybe we should all be a little more — not fanatical, but unreasonable and intransigent in our commitment to truth, to justice, to a better world.

[Rebecca Solnit’s book about disaster and civil society, A Paradise Built in Hell, will be out in time for Katrina’s fourth anniversary. She is a contributing editor to Harper’s Magazine and a Tomdispatch.com regular.]

© 2009 Guardian News and Media Limited

Source / Guardian, U.K.

Thanks to Common Dreams / The Rag Blog

So how would Charles Mansion fit into all of this?

To MASTERSPORK: The author states: "in 1839 to be against slavery in the U.S. was a disruptive, extreme position, often seen as an attack on property rights rather than a defence of human rights." So, it's 'apples vs oranges' to compare Charles Manson to John Brown.

I read with interest your offer: "Tell you what, when I get sent to Afghanistan I will give

The Civil War was not fought over the moral issue of slavery nearly so much as it was the result of two competing economic systems in collision.

Northern industrial capitalism was prevailing economically over Southern agricultural production based on slavery, although there was an uneasy balance of political power.

Good military leadership of the South proved no match for

LOVE this mural detail —- Brother Brown reminds me strongly of several close friends from the 60s, as well as the old family fotos of folks no one can identify anymore — he is letting his freak flag fly!

Fact is — and maybe Bro. Baker was getting to this — the Civil War was apparently inevitable and Brown but a tool in kick-starting it. "Right" and "wrong" are

Deva

The reason why that I brought up Mansion was that they both wanted to incite a revolt among the African Americans.

Let me know if I am being to broad on this.

One needs to be even more specific.

The specific issue John Brown was involved in, the struggle against slavery, came to conflict because the South wanted to extend slavery to the western territories, and the northern Capitalists would not allow that, although they compromised for a decade trying to prevent it, before it came to war. They did, in fact, oppose slavery, but thought it would wither competitively in the south…but more than opposing slavery, they believed in capitalism and wanted to expand it (capitalsim was free farming and free labor). They did not give a hoot about African slaves, other than as economic instruments, nor do they give a hoot about workers today. For their part, the South understood that they were being out competed, and that they would wither without expansion, thus they fought.

I think when situations become, well, war like, then extremists prevail on both sides…its just part of the situation. Knowing when to be what is an art, evidently … so there is a kind of synergy between fanaticism, fanatics, and situations which have boiled into war, or other such drastic social changes.

In such upheavals, in my opinion one is made, not the maker…you either do or do not do what you are asked to do.

Many people, some African, some European by descent, were influenced by the cruelty of forced slavery and thus supported abolition. It was human emotion, not economics that led to the abolition of slavery.

mps

Then if that was the case why did the Loyal slave holding states where allowed to have them until the end of the war?

Masterpork:

If true, which I doubt (you have likely been misled by some right winger, as they are notorious liers who make up fantasy worlds like rats have babies) such things are common in wartime…to maintain a stable economy while the main thing, the war, is resolved.

In this discussion, what is important (not a distraction) is that after the US Civil War, the economy of Kentucky, which was based on selling slaves, utterly collapsed. Ergo, is it not safe to assume that the Emancipation Proclamation was carried out there? Are there any chattel slaves in Kentucky now?

I was raised on stories about the greatenss of Thaddeus Stevens, long before I could read, and most Americans do not even know who he was, so don’t even try to mess with me on this issue.

And the song: “John Brown’s Body lies a moderin in the grave” was commonly sung in my home, although, as usual, without all the lyrics. They could not afford sheet music, which was very expensive back then.

“Many people, some African, some European by descent, were influenced by the cruelty of forced slavery and thus supported abolition. It was human emotion, not economics that led to the abolition of slavery.

mps.”

Well, the people of the South certainly acted out of “human emotion” for their “way of life” and they lost, big time, their beloved “institution” was destroyed and forever.

Trying to fight a war with an entity that is already kicking your economics to hell, and with one coal mine was as brain dead as it gets, I’d say.

In fact, since you mention it, I’d venture to propose that acting out of emotion, as the Confederates did, basing their entire war on the stupid notion that Britain would support them, when Britain wanted to see a consolidation of capitalism globally, not an expansion of slavery, is an indcation that an empire is in superdecline. Or we can mention Hitler’s preposterous emotional notion he could fight on two fronts, and one of them a Soviet nation as well which would not hesitate to mobilize its own people and arm them in Hitler’s rear, something a capitalist nation has never ever done?

Chattel slavery is indeed cruel, but you apparenrly do not realize that it abided several thousand years in the “ancient” world with little disruption (until the likes of Spartacus) simply because people saw no alternative to it, no way out of it.

Chattel slavery in the South of the US was beyond cruel in the imperial commercial context, co-existing beside incipient capitalism, with capitalism’s more lenient free farming and free labor, but its cruelty did not doom it; if cruelty were the motive for change, then the Native Americans would never have been slaughtered by the same General, Sherman, who so bravely took Atlanta from those Confederate slave holding slime.

I do think, however, that human emotion makes a huge difference in tactical situations, like say at Little Roundtop at the battle of Gettysburg, or in the hovels and shelters of Stalingrad, but strategically, nope. The conditions are either there for water to freeze or they are not.

Yup, big win for the northern Capitalist. But not the northern workers who exchanged chattel slavery for wage slavery and now indentured slavery doomed to work soley for the banks and credit card companies….forever or until the stinking corpse of capitalism is tossed on the ashpile of history by emotionally charged rvolutionaries.

That is where I differ with you, Richard…wage slavery is a lot better than chattel slavery. It is still a form of slavery, but its a lot better than chattel slavery.

Capitalism is a lot better than fuedalism…I have two grandfathers who were sharecroppers, and I can assure you, working for wages is better than that, and free farming is better than that too.

Fed: beyond the obvious truth to your statement that working for a living (otherwise called ‘wage slavery’) is better… FAR better than chattel slavery (it’s actually intellectually dishonest to even compare the two as nominal equals), the term ‘capitalist’ in all the posts should be substituted for ‘industrialist’.