Harris County Commissioner Lee was arguably the most powerful Black person in Texas politics.

HOUSTON — Introducing a 2004 Houston Chronicle interview with Harris County Commissioner El Franco Lee, who had then held that office for 20 years, veteran reporter Thom Marshall commented,

While the vast majority of elected officials welcome opportunities to be quoted, a search through Chronicle files… finds many stories containing the phrase, “Commissioner Lee could not be reached for comment.” And while he has quietly avoided the spotlight, the… Precinct 1 commissioner has held on to his job… long enough to become dean [longest serving member – mgw] of the Commissioners Court.

An elected official who doesn’t spend half his time courting the media? What in the world was Lee doing?

He served his constituency in almost

unheard-of ways.

As it turns out, serving his constituency in almost unheard-of ways, diligently promoting the kind of concrete, specific, accessible programs that would most impact and improve lives of Precinct 1 residents.

Health clinics serving expectant mothers, children, seniors, and everyone in between dot the precinct. Parks, trails, lakes, and community centers offer accessible programs in wide-ranging life skills and fun activities from tai chi to fishing. The Street Olympics programs, begun by Lee as a series of summer athletic events to provide something for kids to do during the dog days, now serve thousands of youth year-round and county-wide, with a focus on education and recognizing achievements.

Still called the Street Olympics, the summer games have expanded to include year-round academics, job internships, pregnancy counseling, parenting classes, and other programs that serve youth specifically. Screen grab from YouTube.

Regarding the Street Olympics and its success, County Judge Ed Emmett said, “That wasn’t part of [Lee’s] job; he just felt it was important. He was proudest of the informal things.”

Harris County is the most populous county in Texas and, as of the 2010 census, third most populous in the United States. Its county seat, Houston, is the largest city in Texas and third largest in the nation, and it is home to 34 other incorporated municipalities. A population study completed by the county in January 2015, reported that Harris County had close to 4.4 million residents in 2014, with growth far outpacing both national population growth and the growth rates of Cook County (IL) and Los Angeles County (CA) — the two counties that have larger populations — since the 1990 census.

Harris County is unique in having an unincorporated area that, if incorporated as one city, would be the fifth largest in the U.S. and second largest in Texas. Over 75% of County growth since 2000 has been in its unincorporated areas. It is in there, without city services or ordinances, that county government is most crucial.

Lee had planned to run unopposed for an unprecedented eighth term.

Lee had planned to run unopposed for an unprecedented eighth term as Commissioner, presiding over a 2015-2016 Precinct 1 budget of over $157 million and drawing an annual salary of about $167,000. But on January 4, 2016, after becoming ill at home, he passed away unexpectedly, leaving a void county and Democratic Party officials will be hard-pressed to fill.

During his tenure as Commissioner, Lee promoted dozens of private-public partnerships with nonprofit agencies, the Baylor College of Medicine, and other educational institutions, healthcare organizations, and just about any group that could benefit constituents. He helped lead the Harris County Criminal Justice Coordinating Council to apply for and win a $150,000 grant from the MacArthur Foundation last year to support programs aimed at keeping people out of jail. Affordable housing and assistance for homeless people were also high on Lee’s community-based agenda.

Harris County Aquatics Program participants get important lessons in water safety. Photo from Harris County Aquatics Program.

Teaching inner-city youth the joys of swimming was one of his passions. The Street Olympics exemplified this as well as his propensity for forging partnerships, using Houston Independent School District and other area pools during the summer. In the 2004 Houston Chronicle interview mentioned earlier, Lee said,

What I do is sell the program based on scavenging stuff that is unused and underused. I say, “If you let me use these facilities, I will produce you a student athlete.” All these programs, the common element is that they’re free. All [the kids] have to have is a desire to swim.

Now the Harris County Aquatics Program (HCAP) is just one component of Harris County Street Olympics, Inc., and the swim program’s award-winning team, the Mighty Dolphins, competes successfully in state and national tournaments.

At a Senior Memoir class at the Finnigan Park Community Center, elders learn narrative skills from graduates of the University of Houston’s outstanding Creative Writing program. Marilyn Jones, associate director of the nonprofit Inprint Houston that runs the program, is always looking for new venues to host it, but wants to expand “thoughtfully.” “We look for centers that value learning,” she told the Houston Chronicle last year. A success at Houston’s Jewish Community Center since its inception, the Senior Memoir program’s “solid track record at Finnigan Park” is credited in large part by Jones to Lee’s support.

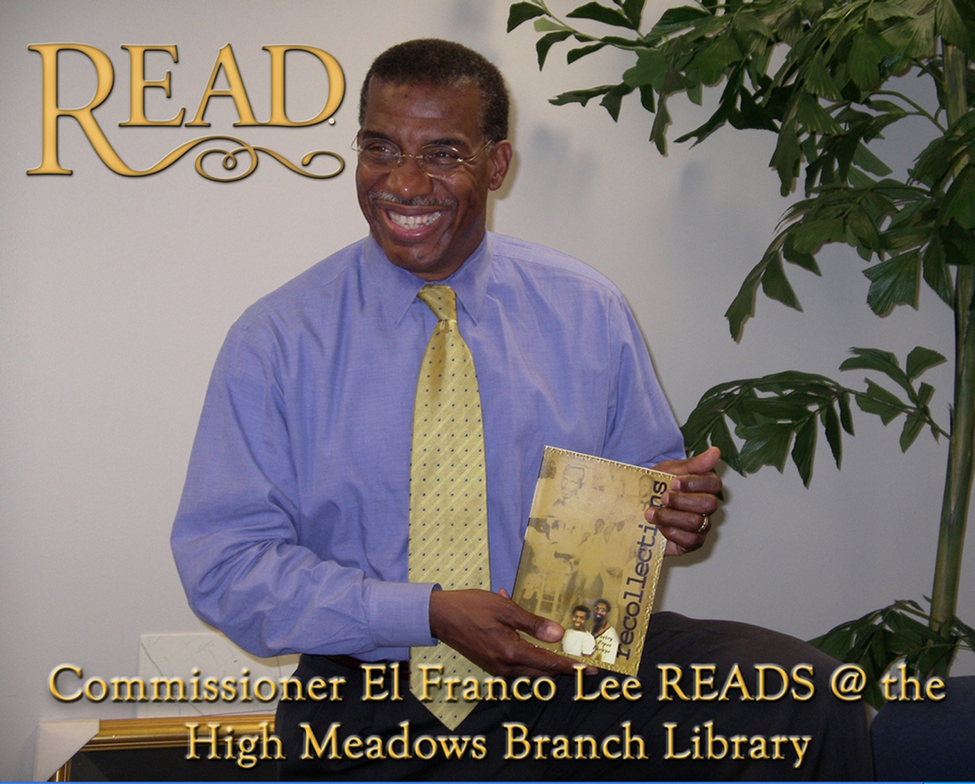

Always a supporter of literacy and reading, Commissioner Lee participated in library programs as a volunteer. Photo from Harris County Public Library / Flickr.

Lee never neglected his brass tacks responsibilities as Precinct 1 Commissioner.

However much he loved these programs and partnerships, however, Lee never neglected his brass tacks responsibilities as Precinct 1 Commissioner. David Benson, one of his chief aides, told the Commissioners Court on January 4,

[He] was super proud of his role as a road, bridge, and park commissioner. He took that very serious. [There] was nothing he liked more than to talk about flood control and ditches and bayous and hydrology and civil engineering and how to bring in the best bang for the buck.

The ability to build parks, roads, and bridges with little legislative interference is one of the prime powers of county commissioners in Texas, and precinct budgets are based in part on the number of road miles they include. In 1984, when Lee ran against Sylvester Turner for the newly redistricted commissioners court seat, Precinct 1 had 160 miles of road versus other precincts, 3,200 miles and an annual budget of $9 million.

Turner, sworn in as Mayor of Houston the day after Lee’s passing, now arguably assumes the role of most powerful Black person in Texas politics.

Lee was the only Democrat now serving, and only African-American ever to serve, on the Harris County Commissioners Court. Both Ed Emmett and Harris County Democratic Party chair Lane Lewis reported that a few overeager individuals had contacted them expressing interest in Lee’s position on the very day his death occurred.

Emmett, a centrist Republican, must appoint someone to fill out the remainder of Lee’s term. Both he and Lewis said they would not consider appointing any of those individuals to serve out Lee’s term or to take his place as the Democratic candidate in November (Lewis’ task). Emmett commented, “There’s such a thing as dignity.”

El Franco Lee was a native of Houston who grew up in Kashmere Gardens.

El Franco Lee was a native of Houston who grew up in Kashmere Gardens, a student athlete on the Phyllis Wheatley High School swim team who married his high school sweetheart and graduated from Texas Southern University with a degree in engineering. He and his family continued to live in his childhood home, updated to include an indoor pool where he swam at least four times weekly. Emmet, who served across the aisle in the Statehouse from Lee, told the Houston Chronicle following Lee’s death, “He didn’t have to take a poll to think about what people in his district thought. He never moved out of the community.”

First elected as a state representative in 1979, part of a young generation of inner-city Black Houstonians who took their inspiration from Texas Sen. Barbara Jordan and included Texas Sen. Rodney Ellis, state representatives Mickey Leland, Harold Dutton, Jr., and Craig Washington; and such other notables as boxer George Foreman and sculptor Bert Long. Texas Monthly magazine named him “Most Underrated” legislator in 1981, and legislative colleagues from both sides of the aisle remember his ability to blindside opponents with cordiality and to cut through red tape.

U.S. Rep. Al Green, a former Harris County Justice of the Peace and former President of the Houston branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), told the Houston Chronicle after Lee’s death that Lee “always sought to get things done rather than have long discussions about those things.”

Precinct 1 was a ‘black opportunity’ district

when it was formed.

Another secret to his success as a commissioner was El Franco’s understanding of the diminishing role of race. Precinct 1 was a “black opportunity” district when it was formed, but it had then and has now a non-black majority. Again referring to the 2004 Thom Marshall interview, in response to a question about being the only African-American on the Commissioners Court, Lee replied,

Race wasn’t the preponderance of my problem when I got here. I was 28 years old when I was first elected to the Legislature, and I was 35 when I was elected to County Commissioners Court. The nearest person to my age was 20 years older than me. So I learned real quick that the preponderance of my problem wasn’t race; it was generational.

I was the first African-American elected in 167 years, but the plight that I was faced with was how I was going to deliver services and… achieve equity. The budget is based on road miles…. I had to come up with some real innovative ways to do the same thing with less money. Now, having been raised up with limited means, I had to call upon a lot of that experience. I could stretch a dollar.

And I’ve been through two cycles of redistricting, and I draw real well.

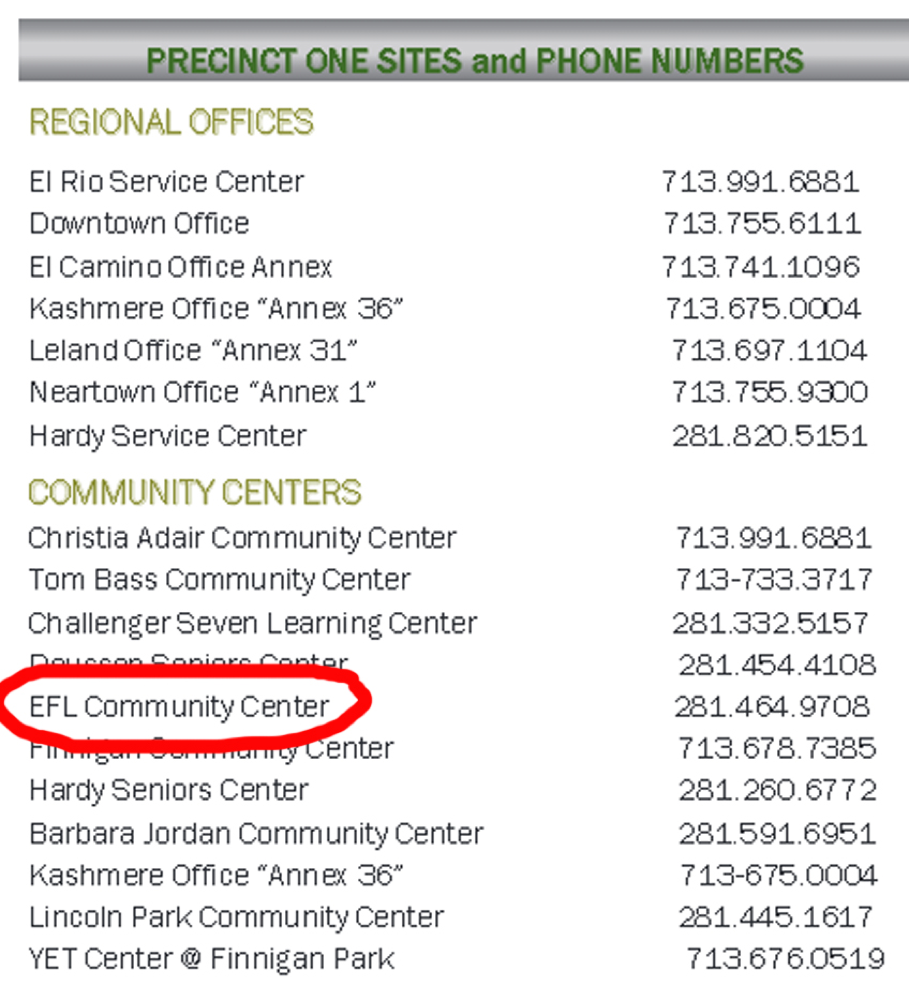

Avoiding the limelight didn’t at all mean that Lee was oblivious to politics. A community center in Precinct 1 is named for him, although the precinct newsletter, One To One, modestly calls it the EFL Center. The internship program he pioneered for county youth, formally the Leadership Experience & Employment Program, is best known by its acronym, the LEE Program.

Lee’s impact on county health services

was profound.

Lee’s impact on county health services was so profound that a fellow commissioner, Precinct 3’s Steve Radack, named a health center in his district for Lee. A park in Precinct 1 was re-named El Franco Lee Park upon successful petitioning by nearby residents, who said they would never have had the park had it not been for his vision and determination.

Lee leaves behind a campaign fund of over $4 million. It seems that a case can be made that consistent and sincere service leads to political success, a lesson many political aspirants might study to their — and our! — benefit.

Gregarious and community-centered, El Franco did not let politics devour his life. He was devoted to his wife, two children, and extended family. He found time to volunteer in causes dear to him personally. His survivors include elder brother Bob, a former Black Panther Party organizer and long-time social service activist known informally as “Da Mayor of Fift’ Ward.” El Franco often credited Bob as his lifelong mentor and chief advisor.

Gregarious and community-centered, El Franco did not let politics devour his life. He was devoted to his wife, two children, and extended family. He found time to volunteer in causes dear to him personally. His survivors include elder brother Bob, a former Black Panther Party organizer and long-time social service activist known informally as “Da Mayor of Fift’ Ward.” El Franco often credited Bob as his lifelong mentor and chief advisor.

On a visit to Bob’s home last year, after El Franco had dropped in to say hello, I saw the man at work as he was trying to leave. An elderly homeowner across the street spotted and hailed him. Upset about something, she expected her commissioner to take care of it, and I watched as he listened carefully and respectfully for a good 20 minutes before proposing a solution. Like the great majority of his other constituents in Precinct 1, he left her with a smile on her face.

His successors will likely be judged for a long time on their ability to do the same.

[Ed note: Former Harris County Attorney Gene Locke has been appointed to fill the remainder of El Franco Lee’s term (through Dec. 31) and State Sen. Rodney Ellis — who otherwise would run opposed in primary and general elections for his current position — has announced that he, instead, is asking Harris County Democratic leaders to select him to be Precinct 1 Commissioner. If chosen, Ellis will make about $160,000 a year more than as a state senator ($7500).]

Read more of Mariann Wizard’s writing on The Rag Blog.

[Rag Blog contributing editor Mariann G. Wizard, is an Austin-based writer and activist. Her website is www.Wordsworth.biz.]