Noam Chomsky salutes left wing daily

Keynotes La Jornada anniversary event

The first issue of La Jornada rolled off borrowed presses September 19th [1984] to the universal disdain of Mexico’s ruling class which then maintained a hammerlock on the press…

By John Ross / The Rag Blog / September 27, 2009

MEXICO CITY — Seven mornings a week, Vicente Ramirez’s battered aluminum kiosk on Cinco de Mayo Street in this city’s old quarter is plastered with the front pages of 22 daily newspapers. All day handfuls of pedestrians pause to gawk at the incendiary headlines slapped to the siding, often engaging in animated debate about the nature of the news.

“This country is going down the toilet,” sneers one elderly gentleman studying a story about a particularly cruel kidnapping. “Ay Mamacita” another old gaffer exclaims, oogling a bare-breasted senorita.

Fully a quarter of the score of dailies on view at Vicente’s kiosk are dedicated to the “nota roja” or “red note.” Tabloids like La Prensa (reputedly Mexico’s biggest seller but circulation figures are elusive) and Impacto are all blood and tits, spotlighting brutal beheadings, sensational crimes of passion, and bevies of topless lasses.

Three sports dailies including the venerable Esto, which still publishes in sepia, rivet the ad hoc attentions of passerbys. Two financial papers (El Financiero and El Economista), The News (a re-incarnation of the long-lived English-language paper) and El Pais, or at least the Mexican edition of the prestigious Madrid daily, dangle from Vicente’s stand. Noontime and evening editions of Mexico City papers will join the display during the day.

Editorial slants run from hard right to soft left — Cronica, reputedly financed by the reviled ex-president Carlos Salinas, savagely slams the left-center Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) that has managed the affairs of the capital for the past 12 years.

Many of the dailies hung from Vicente’s kiosk exist only to cadge juicy government advertising and are hesitant to bite the hand that feeds them. Excelsior and El Universal, broadsheets founded in the midst of the Mexican Revolution not quite a hundred years ago, make much of their “impartiality” but are intractably linked to the once and future ruling PRI party.

Reforma and its tabloid sidekick Metro are sounding boards for the right-wing PAN of which President Felipe Calderon is king — both are unavailable at Vicente’s kiosk, having broken with the powerful Newspaper Venders Union, and they now field an army of comically uniformed street hawkers.

The only openly left wing daily in this vast array, La Jornada (“The Work Day”), is Vicente’s best seller at 20 a day, followed by La Prensa (15) and Universal (10.) When leftists gather in the nearby Zocalo plaza, usually for events captained by ex-Mexico City mayor Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO), Vicente will sell up to a hundred Jornadas.

One caveat: despite this monumental exhibition of newsprint and dead trees, the first news source for 95% of all Mexicans is still the nation’s two-headed TV monopoly, Televisa and TV Azteca.

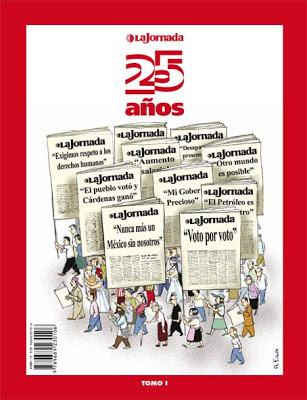

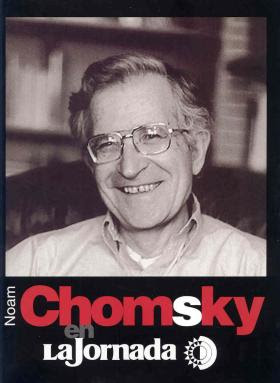

September has been a big month for La Jornada. To celebrate its 25th birthday, the National Lottery offered a commemorative ticket as did the Mexico City Metro subway system, rare mainstream honors for a lefty rag, and notorious U.S. rabble rouser Noam Chomsky came to town to help cut the cake — along with Gabriel Garcia Marquez (a founding investor) and the much-lauded Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano, Chomsky is one of several literary superstars whose words fill the pages of La Jornada.

The Jornada was founded in 1984 by itinerant journalists who had bounced from one short-lived left periodical to the next — for many of the original Jornaleros, like LJ’s first editor Miguel Angel Granados Chapa, the last ports of call had been Uno Mas Uno (“One Plus One”) and El Dia but when their publishers were bought off by then-president Miguel De la Madrid, the lefty newshounds trundled their old Underwoods (computers were nowhere on the horizon back then) up the winding stairs of La Jornada’s old ramshackle headquarters on Balderas Street’s newspaper row and went to work.

Nostalgia was on the menu for La Jornada’s 25th. During one celebration under chandeliers at the elegant Casa Lamm where the paper presents weekly forums on burning social issues, founding director Carlos Payan recalled how in February 1984 he summoned movers and shakers from a broad spectrum of the Mexican Left to the phantasmagoric Hotel Mexico, the unfinished dream of Spanish visionary Manuel Suarez with a revolving rooftop restaurant (it has since been converted into Mexico’s World Trade Center.)

800 potential investors showed up at the assembly, buying in at a thousand pesos a share — one of those on hand was Carlos Slim, now the third richest tycoon on the planet but then still a two-bit corporate cannibal who shared Payan’s Lebanese ancestry. Two of Mexico’s most illustrious painters, Rufino Tamayo and Francisco Toledo, donated priceless works that became La Jornada’s principal capital.

Payan’s words to those gathered in the Insurgentes Avenue ballroom that night ring just as true today as they did back then: “In this hour of crisis, we convoke a new labor of critical journalism in solidarity with those who struggle for the causes of this country.”

The first issue of La Jornada rolled off borrowed presses September 19th of that year to the universal disdain of Mexico’s ruling class which then maintained a hammerlock on the press, doling out government advertising and even newsprint to newspapers based on their allegiances to the PRI and the government it commanded. The barons of the press gave the left daily a few short months of life at best.

La Jornada was indeed born into turbulent times — always a propitious moment for independent journalism. Mexico had just gone belly up, forced into default of $100,000,00,000 USD in short-term foreign bank loans by plunging oil prices, and the crisis kicked the legs out from under outgoing president Jose Lopez Portillo and his hand-picked successor De la Madrid. Wars fomented by U.S. proxies were raging in neighboring Central America — two of the paper’s veteran reporters Carmen Lira (now Payan’s replacement as director) and Blanche Petrich (winner of the National Journalism Award) made their bones in El Salvador and Nicaragua.

On the first anniversary of La Jornada’s birth, Mexico City was savaged by an 8.1 grade earthquake that took up to 30,000 lives and when the “damnificados” (survivors) built a social movement that triggered the resurgence of Mexican civil society, La Jornada became its voice.

The left daily’s history is built on such dramatic moments. During and after the stealing of the 1988 presidential election from leftist Cuauhtemoc Cardenas by the evil Salinas and the PRI, La Jornada stood on the front lines, exposing the fraud that included everything from tens of thousands of burnt ballots to crashing computers, and the paper accompanied Cardenas when he consolidated the PRD in 1989 — the Jornada is often accused of being the left-center party’s mouthpiece.

In the aftermath of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, also in 1989, La Jornada played a critical role in the debate about the future of the Mexican Left and the left press.

The Zapatista rebellion in Chiapas that exploded on January 1st 1994 further burnished La Jornada’s bonafides and sold tons of papers for Vicente Ramirez. Petrich rode into the jungle on horseback and got the first interview with Subcomandante Marcos and Hermann Bellinghausen, another National Journalism Award winner (he turned it down) has reported daily from that conflictive zone ever since.

As the ’90s ebbed into the new millennium, La Jornada closely covered the collapse of the PRI and the installation of the rightist PAN in Los Pinos, the Mexican White House. The paper’s platoon of mordant, militant political cartoonists continue to relentlessly lampoon and skewer the political class.

For the 12 years that the PRD has administered the affairs of this monstrous megalopolis, La Jornada has provided critical support and has, in fact, played a key role in the democratization of the most contaminated, crime-ridden, corrupt and chaotic city in the western hemisphere.

The left daily’s reportage of the heist of the 2006 “presidenciales” by Felipe Calderon from Lopez Obrador — who still enjoys the blessings of the Jornaleros — became Vicente Ramirez’s bread and butter. “I sold a ‘chingo‘ (‘a fucking lot’). They flew out of here like “balas” (‘bullets’).”

Giving this bold trajectory and because LJ has never been “a yes man for the corrupt governments of the PAN and the PRI” (Lira), the paper is despised by right-wingers and establishment intellectuals. Historian Enrique Krauze’s vitriol at La Jornada is splattered all over the glossy pages of his Letras Libres. Writing in Krauze’s rightist monthly, poet-philosopher Gabriel Zaid bemoans the influence that LJ has accumulated over the years: “how can La Jornada have so much weight when important decisions are taken in this country?” he complains, blaming the paper’s “opportunistic” use of culture. “La Jornada brings together left intellectuals who define what they think is political correct.”

Every morning, LJ’s letters to the editor column is packed with bristling epistles from government flunkies assailing La Jornada reporters for exposing the shenanigans of the bureaucracy. When the left paper reports on the dirty dealings of provincial governors and their abuses of authority, the governors are apt to send agents into the street to confiscate every Jornada in the state.

State and federal governments threaten the withdrawal of paid publicity but LJ’s clout has often nullified the denial of this lifeblood of the Mexican newspaper industry. For its 25th anniversary edition, mortal foes of La Jornada like Oaxaca’s tyrannical governor Ulises Ruiz, the Falangist state government of Guanajuato, and the Zapatista-hating mayor of San Cristobal de las Casas were all obligated to take out paid birthday greetings.

While the corporate newspaper industry appears to be gasping its last in the United States where no comparable left daily has ever survived for longer than two years (PM in New York City in the late ’40s), Jornada runs in the black.

Although La Jornada is published in Mexico City, the hub of a highly centralized nation from which all power emanates, the Jornaleros have mothered affiliated dailies in eight Mexican states and the national edition is distributed from Tijuana to Tapachula on the southern border where eager readers snatch up the paper the moment it hits the stands. In addition to the print edition, La Jornada On Line receives thousands of hits each day and has attracted a lively community of bloggers.

Despite its long reach into the provinces, La Jornada is anything but provincial. Its correspondents prowl New York and Moscow and Havana, Bolivia and Chile and Argentina. The newspaper’s perspective is firmly grounded in the global south but Robert Fisk and Patrick Cockburn share their London Independent dispatches from Middle East hotspots.

This correspondent reported on the first days of Bush’s illegal invasion of Iraq from Baghdad. Similarly, David Brooks covered the 9/11 terror attacks on New York and Washington from Ground Zero. Luis Hernandez Navarro never misses an international anti-globalization mobilization or World Social Forum. Cronista (chronicler) Arturo Cano hangs out with Mel Zelaya in Tegucigalpa.

La Jornada does not only print the news, it makes it, actively espousing social causes and decrying injustice daily on its pages. In fact, the resistance of marginated communities from Chiapas to Pais Vasco would be little noted if the news had not first run in La Jornada. Crucial to this insemination of resistance in Mexico are daily notices of meetings and forums and rallies and marches that act as a mighty force multiplier for left movements, turning handfuls into multitudes. La Jornada, whose strong suit is reporting on social movements, has itself become a social movement.

Although politics are its main course, La Jornada publishes monthly supplements on agriculture, the environment, labor, indigenous cultures, women’s struggles, and gay and lesbian rights. The weekly cultural insert and daily reports on painting, dance, literature, music, and popular entertainment have deep scratch among cultural workers.

The Jornada even once published a weekly magazine in English, a losing commercial venture that was eventually killed by Lira. “We are not going to spend the benefits of our workers” by continuing to publish a magazine “in the language of the oppressors,” Carmen explained to this writer at the time. Jornada workers have built a strong in-house union.

La Jornada also operates a book publishing arm with dozens of titles authored by its own reporters like Bellinghausen’s account of the massacre at Acteal, “A Crime of State.” Translations of Noam Chomsky’s multiple works are hot sellers.

Despite hard-wired anti-gringo sentiments, La Jornada invited the renowned gavacho gadfly to crown its 25th birthday celebration with a magnum lecture at the National University. Noam Chomsky is hardly the only U.S. lefty to adorn LJ’s op ed columns — Howard Zinn, Immanuel Wallerstein, James Petras, and Amy Goodman are regular collaborators.

In introducing his September 21st lecture at the UNAM, the oldest and most prestigious in the Americas, Carmen Lira posited that Chomsky’s analysis of mass media in writings like “Manufacturing Consent” and the ethical guidance of the late Polish journalist Ryzsward Kupascinski (“bad people cannot become good reporters”) were the cornerstones of La Jornada’s credo.

Chomsky’s near two-hour talk to a jam-packed auditorium named for the poet-king Nezahualcoytl (every seat in the house was claimed within 30 minutes of the announcement of the lecture) lazered in on Washington’s fading domination of a uni-polar world. Noam ranged far afield: how Barack Obama, the darling of Wall Street, was sold to the North American electorate “like toothpaste or a wonder drug;” the British Empire as the “first international narco-trafficker” (the Opium War); the strategic perils of U.S. bases in Colombia for the Global South. The elderly (82) MIT linguistics pioneer’s discourses are often better read on the printed page than pronounced out loud and Chomsky’s low-key, nebbishy persona left some attendees dozing despite the dazzling blizzard of data he offered.

Focusing on Washington’s crimes around the globe, the talk often approached the world on an west-east power bias rather than south to north, mentioning NATO more than NAFTA with no reference to new Latin Left leaders like Hugo Chavez with whom Chomsky had just huddled. The perennial icon of the U.S. Left also avoided much mention of contemporary Mexican politics, perhaps with an eye out for Constitutional Article 33 that gives the Mexican president carte blanche to kick out any “inconvenient” foreigner. Still, the old gringo’s condemnation of free trade, the war on drugs, and neo-liberal economics must have made Felipe Calderon (whose name was never dropped) uncomfortable.

Despite the length of the talk, Chomsky was only twice interrupted with applause — once when he advanced that like the U.S., Mexico was not a “failed state” (a favorite theme) at least for the oligarchy but for millions of the poor who have lost all social protections, the state has, in fact, failed. When Noam Chomsky counseled that the best cure for neo-liberal excess was to confront the rulers with mass mobilizations, the audience again broke into cheers.

As the very professorial Noam Chomsky stepped from the podium he was greeted by Trinidad Ramirez, wife of the imprisoned (113 years) Ignacio del Valle, leader of the Popular Front for the Defense of the Land, who tied a red kerchief around his neck and presented him with the emblematic machete of the farmers of San Salvador Atenco who count 13 political prisoners among their ranks.

After 25 years and upwards of 9000 editions, La Jornada has forcefully disproved one of Noam Chomsky’s pet theses: that an independent media cannot survive in a corporate-dominated press. “You’ve proven me wrong,” the old professor sheepishly confessed during a visit to the paper’s Spartan headquarters in the south of the city.

“Nine thousand editions! You’ve got be kidding!” Vicente Ramirez marveled in his cramped little newspaper kiosk, whipping out his pocket computer. “Lets see – 9000 editions at 10 pesos a piece times 20. That’s 1,800,000 pesos! Happy Birthday! La Jornada has been very good to me.”

[John Ross’s monstrous El Monstruo – Dread & Redemption In Mexico City will hit the streets in November (to read raving reviews from the likes of Mike Davis and Jeremy Scahill go to www.nationbooks.org.) Ross will be traveling Gringolandia much of 2009-2010 with El Monstruo and his new Haymarket title Iraqigirl, the diary of a teenager growing up under U.S. occupation. If you have a venue for presentations he would like to talk to you at johnross@igc.org.]