Now this is grassroots organization. We could take a lesson from their effort. You don’t get anything if you don’t ask for it.

Richard Jehn / The Rag Blog

South African Children Push for Better Schools

By Celia W. Dugger / September 24, 2009

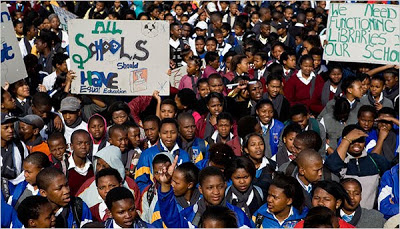

CAPE TOWN, South Africa — Thousands of children marched to City Hall this week in sensible black shoes, a stream of boys and girls from township schools across this seaside city that extended for blocks, passing in a blur of pleated skirts, blazers and rep ties. Their polite demand: Give us libraries and librarians.

“We want more information and knowledge,” said a ninth grader, Abongile Ndesi.

In the 15 years since white supremacist rule ended in South Africa, the governing party, the African National Congress, has put in place numerous policies to transform schools into engines of opportunity. But many of its leaders, including President Jacob Zuma, now acknowledge that those efforts have too often failed.

The new protest movement, with its practical goals, youthful organizers and idealistic moniker, Equal Education, is a quintessentially South African answer to a failing education system, one that self-consciously acknowledged its debt to the past in the march to City Hall.

In 1976, when police officers shot a 13-year-old named Hector Pieterson in Soweto, a children’s uprising against apartheid emerged and spread across the country to Cape Town, where students from a mixed-race high school, Salt River, marched in solidarity with black schoolchildren.

Zackie Achmat, South Africa’s wiliest campaigner for AIDS treatment, was himself a 14-year-old marcher that September day 33 years ago. Mr. Achmat, now graying, was among the protesters following the same route this week, his white straw hat bobbing in a sea of plaids and ginghams.

The idea for a new movement dedicated to educational equity was his, and he helped nurse Equal Education into being, counseling its young leaders to work with teachers and government officials whenever possible. The country’s leadership, which has been slow to grapple with the AIDS crisis, understands the urgent need for better education, he said. The new director general of the country’s Higher Education Ministry, Mary Metcalfe, has served as head of Equal Education’s board.

“In building a citizens’ movement, the most important element is giving people the sense of their own power to change things with little victories,” Mr. Achmat said.

The job of organizing the group has fallen to a pair of law school graduates from the University of Cape Town. Doron Isaacs, 29, its coordinator, was leader of Habonim South Africa, an organization of young, left-wing Jewish activists with whom Mr. Achmat has worked for years. Mr. Isaacs recruited a classmate, Yoliswa Dwane, 27, who was raised by her seamstress mother and now lives in a shack in the township of Khayelitsha, south of Cape Town, where she is caring for nieces, ages 12 and 17.

Last year, Equal Education gave students in Khayelitsha, home to more than 500,000 unemployed and working-class people, disposable cameras to document problems in their high schools. They returned with shots of leaking roofs, cracked desks and children crowded around a single textbook.

One image — a bank of window panes at Luhlaza high school, all shattered, captured by a student named Zukiswa Vuka — proved the most resonant. Some 500 windows at the school had been broken for years, leaving the students shivering in wintertime classes.

Equal Education’s first campaign was to get them replaced. The school agreed to put up about $650, an amount the group said it would match. That left some $900 still needed. Over months, the group met with local and provincial managers, organized a communitywide petition drive, held a rally of hundreds of township students and garnered coverage in local newspapers.

Finally in November, provincial education officials announced that the windows would be fixed and that a sum almost 10 times what the students had requested would be invested in the school.

This year, students successfully agitated for a science teacher at Chris Hani High School when it had none for the seniors.

They also led a drive to get their classmates to come to school on time, with early-morning pickets at school gates — an effort that also showed up late-arriving teachers.

The libraries campaign is the group’s first attempt to tackle a national issue. With financial support from Atlantic Philanthropies and the Open Society Institute, among others, it is also hoping to broaden its membership to include teachers and more parents and to graduate to bigger victories.

Mr. Isaacs said Equal Education’s members knew that problems far harder to fix than windows or missing libraries awaited and that part of the answer was building alliances with the teachers’ union, which is in the governing alliance.

“We know that the teachers’ union is one of the most powerful institutions in the country,” he said, “and if we style ourselves as its adversary, we’ll be dead in the water.”

The marchers, stretched out Tuesday along Main Road in the shadow of majestic Table Mountain, were themselves a wealth of stories.

Nkosinathi Dayimani, a senior, was one of the beneficiaries of the new science teacher this year, but not soon enough to prevent his failure on the recent trial run of the national science exam.

Asanda Sparks, a petite ninth grader from Kraaifontein Township, has been hoping for a library in her school since bullies picked her pocket as she walked to the public library to research Nelson Mandela’s life.

And Nina Hoffman was among the dozens of white students who joined the march from one of the country’s formerly all-white suburban high schools — Westerford — which can afford a well-stocked library because parents pay annual fees of more than $2,200 per child.

“Coming to a march like this, I realize even more how privileged we are and how much I take for granted,” she said.

During their two-hour walk to City Hall on a gloriously sunny afternoon, the young people seemed buoyed by the hope of making a difference.

Abongile, the ninth grader from Luhlaza high school, noted appreciatively that she did not have to sit with chattering teeth in class this winter because the broken windows had been fixed.

“I saw that Equal Education can make something impossible possible,” she said.

Source / New York Times

Good post. Unfortunately the conditions described, rather reminded me of the inner city school where I taught: the multiple broken windows in my own “temporary” movable classroom were never repaired during my tenure; trash piled up beneath the splinter-laden wooden ramp leading to my “classroom door”; two armed guards patrolled the campus; the state-mandated text books were written in “grade appropriate” standard English – but 87% of my students were ESL and literally unable to read those books; I bought all my own supplies and teaching materials. And this was all in sunny Southern California. It’s not impossible to teach or learn effectively under these conditions, but it’s hard, spirit-crushing hard. South African children need and can benefit from better books, dedicated teachers, facilities, everything. But the gap between the education of the privileged & non-privileged is hardly unique to SA. Look around folks – maybe it’s time American students rise up and march, asking more of their parents, school districts, state Bds. of Ed. local and national legislators. (And I’ve a brilliant idea on how to fund this education project: stop waging war elsewhere! Why we might even have enough money left over to help some of those SA school kids.

the difference i see in the s.a. example is solidarity with the teachers.

in the u.s. teachers leave for greener pastures after short t.f.a. stints never looking back.

JJ – Please cite your sources for your claim that in the U.S. teachers “leave for greener pastures after short tfa stints never looking back”. Surely you wouldn’t make such a sweeping and derogatory comment without evidence?

the past tense the first anonymous poster used was the inspiration. the google machine gave me 66,100 results.

here’s one.