One Texas scholar insisted that Johnson’s strong spiritual conviction and moral obligation fueled this alleged clandestine undertaking.

HOUSTON — On the evening of December 30, 1963, a little more than one month after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the newly sworn-in 36th President of the United States kept a promise he made to the congregants of a small Jewish Conservative synagogue in Austin, Texas.

At the personal request of his good friend Jim Novy, a political ally and a central Texas Democratic Party fundraiser, Lyndon Baines Johnson addressed the members of Congregation Agudas Achim at a dinner dedicating their new sanctuary, then located on Bull Creek Road. The dedication was originally scheduled for the evening of November 24, but the events that transpired two days before in Dallas, beginning with a motorcade through Dealey Plaza, prevented Johnson from fulfilling his original promise.

LBJ stepped up to the podium to address a grieving congregation.

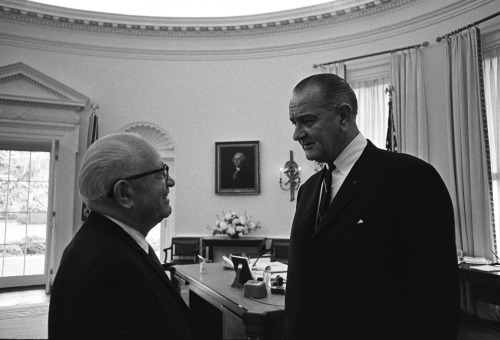

This was Johnson’s first public speech since taking the oath of office to become acting president of the United States. However, before LBJ stepped up to the podium to address a grieving congregation, he was first introduced by Novy, a self-made Polish immigrant and chairman of the synagogue’s building committee. Novy’s remarks were recorded and later reproduced on a commemorative analog vinyl disc that was distributed as a souvenir to all who were in attendance that evening.

In his Texas drawl with a slight Yiddish accent, the diminutive and bespectacled Austin scrap-metal magnate greeted the congregation and thanked LBJ for his involvement in what has become a historical and political mystery, puzzling both academics and historians for more than 50 years. Jim Novy’s introduction that night lit a fire of conjecture regarding a questionable and often disputed chapter of American history that has been steadily smoldering to this day:

“I want to take you back as far as 1938 when I went to Poland and Germany with my son, Dave Howard,” Novy began. “Naturally, I asked the advice of President Johnson. He had given me a letter for the [U.S.] embassy in Poland and went as far as calling them long distance to tell them to get as many people out of Poland and Germany that we possibly can and of course, through the efforts of the President, and with a recommendation to the embassy, we were able to take many, many people out.”

In July 1938, LBJ, with Novy’s help, allegedly set the wheels in motion to covertly rescue a group of Polish and German Jews, including Novy’s sister-in-law and her three children. When Novy took a business trip to Warsaw with his young son that summer, in his possession were the necessary affidavits and departure visas, provided by Congressman Johnson, that enabled 42 Jews to leave prewar Europe and circumvent the United States’ existing restrictive immigration policy.

These refugees supposedly entered the United States through the port of Galveston.

These refugees supposedly entered the United States several months later through the port of Galveston, and were then resettled in central Texas. In 1940, before Germany officially declared war on the United States, Johnson and Novy may have orchestrated another clandestine rescue of hundreds more. As a result, these Polish and German rescuees were saved from the imminent systematic annihilation of European Jewry by the hands of the Nazis.

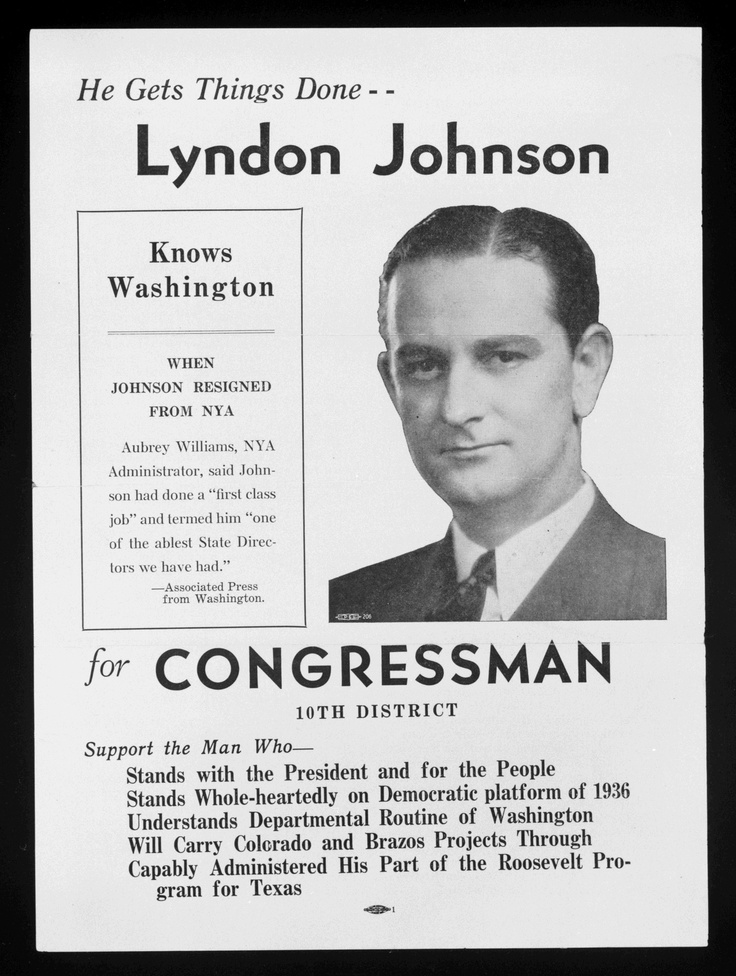

As Novy nervously continued introducing LBJ at Congregation Agudas Achim that evening, he moved two years forward in his story. He explained how after the second wave of refugees were brought to Texas, they were housed and trained in Depression-era NYA (National Youth Association) work camps. These “New Deal” camps, created for American citizens by the Roosevelt administration, were designed to teach new trades to America’s unemployed youth, and reintroduce them back into the work force. Johnson was appointed state director of the Texas NYA by Roosevelt, and he handpicked his successor, Jessee Kellam, after his election to Congress in 1937.

“All I can remember is that we did get a lot of refugees here, and which the state didn’t mind to lodge them and teach them trades,” Novy told an attentive audience, “but they [NYA] wouldn’t pay for their food. So, the Joint Distribution Committee at that time appointed me to get all the groceries and all they needed to eat while the State of Texas taught them how to get along in life and to get away from a country where they couldn’t do anything [referring to Germany’s Nuremberg Laws].”

With Secret Service members standing at the back of the room and Lady Bird seated by his side, LBJ patiently waited for Novy to conclude his introduction before he stepped up to the podium to address the audience. Johnson then thanked the congregation for their continual support and only cryptically alluded to the surreptitious episodes mentioned by Novy that purportedly transpired during the freshman year of his eleven-year-term in the U.S. House of Representatives.

LBJ never acknowledged the tale spun by Novy in his introduction, nor did he deny it.

As he read from the speech prepared by White House special assistant to the President Bill Moyers, LBJ never acknowledged the tale spun by Novy in his introduction, nor did he deny it. He did, however, make reference to the diverse cultural and demographic melting pot of Austin’s 10th congressional district that afforded him his political career: “From many lands, from many cultures men brought their families here to escape oppression, to escape war, to search and seek their peace,” he said. “I am grateful that my first nonofficial public remarks since November 22 can be made here in Austin and in conjunction with the dedication of a house of worship.”

At Novy’s request, LBJ’s pro-Zionist aunt, Jessie Johnson Hatcher, and her daughter also attended that evening, as did some of the aging, yet grateful members of the congregation to whom Novy made reference in his introduction.

Lady Bird Johnson also reminisced about the evening of the dedication of the new Agudas Achim sanctuary in her 1970 memoir, A White House Diary: “As we started out the synagogue, person after person plucked at my sleeve and said, ‘I wouldn’t be here today if it weren’t for him. He helped me get out.’ That both frightens you and makes you happy,” Lady Bird wrote.

Neena Husid, an Austin publicist and blogger who worked as an advertising sales rep at KLBJ-FM in the 1980s, remembers being invited to a sales meeting and luncheon hosted by Lady Bird at her downtown Austin penthouse. “As she took me around the apartment showing me artifacts belonging to her late husband, she confided to me with a nod and a wink, ‘The Jews were very good to Lyndon and Lyndon was very good to the Jews.’ I always figured this comment had to do with the fact that Jewish political forces helped him get elected but in hindsight, I think she was trying to tell me something more.”

This little-known dedication ceremony at Agudas Achim in Austin was all but forgotten until 1989, when word spread in academic circles of a dissertation submitted to the chair of the history department at the University of Texas by Louis S. Gomolak, an older-than-average doctoral student.

Gomolak described how first-term Congressman Johnson pulled the right political strings.

In his dissertation, Prologue: LBJ’s Foreign Affairs Background, 1908-1948, Gomolak described how first-term Congressman Lyndon Baines Johnson pulled the right political strings from behind the scenes to circumvent the existing discriminatory U.S. immigration laws and saved hundreds of Polish and German Jews on the eve of the Holocaust. Gomolak insisted that Johnson’s strong spiritual conviction and moral obligation fueled this clandestine undertaking. Gomolak named this episode “Operation Texas” in his dissertation.

Gomolak was the first to theorize that LBJ, with the help of Jim Novy, orchestrated two large-scale covert rescue missions of European Jews, in 1938 and 1940, and several smaller isolated ones. All of these were implemented, Gomolak believed, without the knowledge of the U.S. Government, and without leaving any tangible evidence or a traceable paper trail.

As evidence, Gomolak cited Novy’s dedication speech and Novy’s personal notes where he specifically referenced 42 Jews who were saved on his first mission to Poland. Gomolak also allegedly interviewed several of the rescued refugees who settled throughout central Texas and who were members of Agudas Achim.

Gomalak has been very tight-lipped regarding his sources over the years, and nowhere in the dissertation did he identify these supposedly-saved hundreds by name. Since his dissertation first surfaced, Gomolak’s theory has been the subject of speculation and debate among historians and his academic peers.

Claudia Anderson, supervisory archivist of the LBJ Presidential Library in Austin, first learned of Gomolak’s rescue theory when the library received a copy of the dissertation in 1989. Over the years, she has conducted her own extensive research and combed through State Department archives in an attempt to validate Gomolak’s findings.

Anderson has yet to discover any ‘primary-source proof’ to substantiate Gomolak’s theory.

So far, she said she has yet to discover any “primary-source proof” to substantiate Gomolak’s theory, which has now been relegated to Internet folklore. “I didn’t initially think he had enough evidence to substantiate what he was saying,” Anderson said in regards to Gomolak’s research. “I think he draws conclusions that were not merited by the evidence.”

Anderson believes that Johnson sent Novy to the American consul in Poland in 1938 with a letter explaining that Novy had sponsors in the Austin community who had the financial means to support the refugees once they entered the United States and that they would not become public charges of the American taxpayers. “That is what the State Department was so concerned with back then and used as a means to defend their anti-Semitic actions with regard to refugees and immigration,” Anderson said.

Anderson, however, is also skeptical about the number of Jews who were allegedly transported from Europe and brought, under the veil of darkness, into Galveston Bay: “I know that Novy was a big story-teller and I don’t know how closely he stuck to the facts,” she said. “Before I would buy into the story, we need at least some evidence of who these people [refugees] were or some evidence of another person who could corroborate that number — and right now, we don’t have that.”

Golomak’s dissertation noted that at the time of LBJ’s first purported rescue mission, during Franklin Roosevelt’s second term in office, foreign immigration into the U.S. was still determined by the harsh quota system of the National Origins Quota Act of 1924. Also known as the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act, it limited the annual number of immigrants admitted into the U.S. from any one country to 2% of the number of people from that particular country who were living in the U.S. in the year 1890. This discriminatory piece of legislation passed with overwhelming congressional support, and was signed into law by 30th U.S. President, Calvin Coolidge.

A widespread climate of xenophobia and anti-Semitism existed at the time.

According to Gomolak, this statute was designed to exclude non-Anglo-Saxons — specifically, people from eastern and southern Europe — from entering the U.S. A widespread climate of xenophobia and anti-Semitism existed at the time, and many Americans viewed all immigrants as subversives who threatened America’s social and political stability. The nation was still recovering from the Great Depression, and most Americans favored restrictive laws that protected scarce American jobs and maintained wages for the jobs that still existed.

In the 1930s, the average U.S. citizen condoned America’s isolationist policy, and was only somewhat aware of the oppressive treatment inflicted on Germany’s Jewish population by the Nazis. Articles about the Nuremberg Laws and Kristallnaucht were usually buried in the back pages of America’s daily newspapers. Hitler did not officially declare war on the United States until December 11, 1941, four days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. One day after what Roosevelt referred to as “a date which will live in infamy,” the Nazis experimentally gassed hundreds of Polish Jews in the northern town of Chelmno, as a dress rehearsal for what would become the “Final Solution.”

Gomolak further noted that LBJ first learned the nuts and bolts of how to navigate the bureaucratic maze of America’s immigration policy while he was still an aide to U.S. Congressman Richard Kleberg of Corpus Christi. Johnson discovered that German and Polish entry quotas into Cuba, Mexico, and South America went largely unused, and that he could bring refugees from Europe into those countries. After a period of time, those refugees could then obtain entrance visas into the U.S. and apply for residency.

Johnson was asked to intervene in the case of Jewish-Austrian conductor Erich Leinsdorf.

Johnson put this knowledge to the test after he was elected to Congress. In March of 1938, another one of LBJ’s good friends and political constituents approached him for a favor. Charles E. Marsh, publisher of the Austin American-Statesman, asked Johnson to intervene in the case of Jewish-Austrian conductor, Erich Leinsdorf. At the time, Leinsdorf was working in the U.S. on a six-month visa for the New York Metropolitan Opera.

After being offered a two-year contract with the Met, and learning of Germany’s Anchluss (the annexation of Austria), Leinsdorf applied for an extension to stay in the U.S. The United States Immigration and Naturalization Service denied his request, but Johnson, according to Gomolak, devised a plan to have Leinsdorf’s immigration status changed from visitor to permanent resident. Johnson then instructed Leinsdorf to leave the U.S. for Havana and reenter under the German immigration quota. By 1942, Leinsdorf would become a naturalized American citizen and serve his newly adoptive country in the United States Armed Forces during WWII.

Not all of LBJ’s isolated rescues were as high profile as Eric Leinsdorf’s, nor were they all discovered by Gomolak while researching his dissertation. According to family folklore of the Diskins of Houston, one rescuee in particular, their family patriarch, left prewar Poland with the help of Johnson and Novy before the borders closed, and immigrated to Texas in a very conventional, yet ambiguous manner.

On September 26, 1938, the M.S. Batory, a Polish merchant ocean liner, arrived at Ellis Island in New York harbor after 11 days at sea that included stops at Copenhagen and Cherbourg, France. Listed on the ship’s Manifest of Alien Passengers Bound for the United States were a group of more than 100 Polish nationals of the “Hebrew” race who departed Gdynia, Poland, 11 days earlier.

All of their exit visas were issued in Warsaw in the previous months.

All of their exit visas were issued in Warsaw in the previous months of August and September, and all but two of these Jewish passengers, a rabbi and a Polish government official, told their Ellis Island inspectors when they disembarked that they were seeking permanent residency in the United States. They also said they would not be returning to Poland.

Among the passengers who passed through Ellis Island that day was 26-year-old Icek Diskin, a barber from Warsaw, who reinvented himself as Murray Issac Diskin. Years later, he would become a multi-term city council member and popular clothing retailer (Diskin’s) of Brookshire, Texas.

After answering “no” to the obligatory questions asked by Ellis Island immigration as to whether he was a polygamist or an anarchist, Diskin indicated to the immigration officer that he, too, “would not” be returning to Poland. He listed his final destination as Georgetown, Texas, just north of Austin. There, his older sister and her husband, who had paid Diskin’s passage to the U.S. and his train ticket to Texas, were residing.

Diskin’s sister, Celia Neuman, and her husband Ben, were prominent members of Austin’s Jewish community and Congregation Agudas Achim. In 1938, they learned of fellow congregant Jim Novy’s rescue mission to Poland and asked if he could include her younger brother in his plans. Diskin had never immigrated to the U.S. like his older sister, and chose to remain in Warsaw with his mother.

Although Diskin’s widow, Bernice Diskin Reichstein, maintains that LBJ and Novy helped save her husband, neither she, nor her four adult children, know very much regarding the extent of LBJ’s behind-the-scenes involvement. Nor do they have any credible information of how this episode transpired or the logistics of the purported rescue. Like so many other of LBJ’s rescuees, Diskin neglected to share the details of his story with his immediate family. “When it comes to father discussing his past,” said Diskin’s oldest son, Ira, “he always conveniently had amnesia.”

The Holocaust Museum Houston established the Lyndon Baines Johnson Moral Courage Award.

In 1995, the Holocaust Museum Houston established the Lyndon Baines Johnson Moral Courage Award one year after it opened its doors and received its non-profit 501(c) 3 charter. According to the museum, recipients of this award are individuals, like Johnson, who exhibit moral courage, take personal responsibility, and are willing to take action against injustice. The award is part of the HMH’s annual fundraising activities and outreach program.

Since its inception, the museum has bestowed this honor on 15 distinguished individuals and one deserving European country for altruistic acts that benefited all mankind. Dr. David P. Bell, a longtime member of the HMH board of trustees, believes that Lyndon Johnson, as a congressman, stretched the limits of his authority and risked his political career to rescue European Jews from the Holocaust a mission based on his moral imperative.

“The basis of why we honor LBJ at the museum is because he was a first-term congressman, with his whole future ahead of him, and he took extraordinary risks that would have jeopardized his political career on behalf of people he didn’t know,” Bell said.

When the HMH first learned of Operation Texas in the early 90s, Bell said that the board asked him to travel to Austin to meet Gomolak and investigate his claims about Johnson. Bell was initially convinced that Gomolak’s findings were largely accurate. Now, he said, he is not so sure, and believes that Gomolak may have embellished his research. Bell finds it frustrating that no paper trail regarding Operation Texas exists, plus, there is a reluctance on the part of those rescuees who are still alive to step forward and be acknowledged.

Bell thought that few people were willing to talk about it in fear they would be sent back.

Bell, however, has his own theory why Operation Texas has been so difficult to confirm, and why rescuees are reluctant to make themselves known. “This has been such a hard story to document because so many of the people who were brought into the U.S. by Novy and LBJ were led to believe that what happened was illegal,” Bell explained. “Therefore, even years later you find very few people who were willing to talk about it in fear that they will be sent back.”

LBJ and Lady Bird were regular fixtures at Trinity Lutheran Church in Stonewall, Texas, just east of Fredericksburg, where they attended Sunday services. However, Johnson, according to Gomolak, was influenced and spiritually nurtured by his grandfather, Sam Ealy “Big Sam” Johnson, Sr., and his youngest aunt, Jessie Johnson Hatcher. They were both practicing members of the Christadelphian faith, or “Brethren of Christ.” Big Sam and Aunt Jessie were also fundamentalist Christian Zionists, long before it became trendy among present-day televangelists and ultraconservative, right-wing Republican politicians.

Gomolak claimed in his dissertation that LBJ’s motivation for Operation Texas came from his indoctrination, at an early age, into the Christidelphian sect. Founded in 1834, today’s practicing Christadelphians hold firmly to the teachings of Dr. John Thomas, an English physician who brought the faith to the United States. Christadelphians subscribe to the literal eschatology of Scripture, and like all evangelical, fundamentalist Christians, believe in the millenarian “end of days” scenario as prophesized in the New Testament’s Book of Revelation.

Christadelphians also believe in God’s covenant with Abraham, written in the Book of Genesis of the Old Testament. In Genesis 12:3, God says to Abraham: “I will bless those who bless you and I will curse those who curse you and in you all the families of the earth will be blessed.”

LBJ Presidential Library archivist Anderson describes Johnson’s approach to religion as “very eclectic,” and that this personal belief system played an important role in his concern for the underprivileged and his strong sense of populist politics in the 1930s. Although LBJ was introduced to Zionist ideas through his family’s Christadelphian faith, Anderson believes he never actually adopted that sect. “I think he had a strong spirituality and a strong fundamental belief, but it wasn’t so focused on a particular denomination,” she said.

Regarding LBJ’s dedicated relationship with Austin’s Jewish community, Anderson surmises that it was complicated. “How do you separate friendship, political advantage, and religious moral belief when there could have been elements of all of them? You really can’t draw a pie chart.”

On October 3, 1965, as a symbolic gesture, LBJ signed the Hart-Celler Act into law at the foot of the Statue of Liberty. This statute forever abolished the U.S. Government’s attempt to unjustly restrict immigration. And as the 16mm black and white film cameras documented this event for the three major television networks, Johnson addressed the American people: “This [old] system violates the basic principle of American democracy, the principle that values and rewards each man on the basis of his merit as a man, and it has been un-American in the highest sense, because it has been untrue to the faith that brought thousands to these shores even before we were a country.”

Although Operation Texas makes for an intriguing story, no hard, substantive evidence proves or disproves the existence of these clandestine rescue missions. According to Anderson, official Lyndon Johnson biographer, Robert Caro, is well aware of the mystery surrounding Operation Texas. Nevertheless, Caro has never written a single word about this supposed episode of LBJ’s life in any of his four published volumes. And as time passes, hope of any living person coming forward with first-hand knowledge or tangible proof diminishes.

At the time of this writing, neither the reclusive Dr. Louis S. Gomolak, now a retired college professor at Southwest Texas State University in San Marcos (renamed Texas State University), nor LBJ biographer Caro, has responded to my requests for an interview. Former LBJ staff member, Bill Moyers, told me via email he had no recollection of a speech he wrote for Lyndon Johnson or the dedication of the Agudas Achim synagogue in Austin where it was delivered on the evening of December 30, 1963 — a little more than one month after the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

[Ivan Koop Kuper is a freelance writer, a real estate broker, and a professional drummer. He is still a graduate student at the University of St. Thomas in Houston, and can be reached for comment at kuperi@stthom.edu. Find more articles by Ivan Koop Kuper on The Rag Blog.]

Great Work, Koop! Over the years, I have been rather lonely in my belief that LBJ would eventually be recognized as one of the Great Moralistic President of Modern Times. This just adds to my belief. Thanks.

Interesting article! Thanks Koop!