Micheletti responds with curfews, teargas…

Massive demonstrations mark Zelaya’s return

By David Holmes Morris / The Rag Blog / September 14, 2009

See more photos of the action, Below.

What began on Monday as a celebration of Manuel Zelaya’s surprise return to Honduras, on Tuesday turned into yet another struggle against the violent repression of his supporters by the golpista government that had deposed him almost three months earlier.

After he announced several times during his exile that his return was imminent and after two actual attempts to enter the country, word spread quickly on the morning of Monday, September 21, that Zelaya was at the United Nations offices in Tegucigalpa, then that he was in fact at the nearby Brazilian embassy. As zelayistas and contragolpistas gathered in great numbers outside the embassy and others made their way toward Tegucigalpa from across the country, Zelaya told reporters inside that he and four companions had traveled in secret for 15 hours through mountains and forests with the aim of negotiating the terms of his reinstatement with Roberto Micheletti and the rest of the golpista regime.

“I speak to you as commander in chief of the armed forces of Honduras, whom the people elected to lead them and who always offered them a warm handshake,” he declared in a message to supporters and, especially, to the soldiers who would soon surround them. “I appeal peacefully to your wisdom: let there be no violence in the streets. The people here with us are unarmed, shouting joyful slogans because this is a day of celebration.”

When he addressed them directly from the roof of the embassy, supporters sang Las Mañanitas in celebration partly of his return and partly of his birthday, which, coincidentally, had been the day before.

Micheletti at first dismissed news of Zelaya’s return as “media terrorism” propagated by his supporters. Zelaya, he assured reporters, was lounging in a hotel suite in Managua. His own intelligence officers had told him so.

The truth must have shocked Micheletti and would certainly have embarassed him. Zelaya and others in the resistance had been saying all along that many of the country’s military and police officers disapproved of the coup government and would in the end rebel against it. Zelaya might well have had their active support in entering the country and making his way undetected from the Nicaraguan border to the capital.

Resistance leader Juan Barahona predicted that day that the coup government would fall within 24 hours and that Micheletti would be taken prisoner. Rumors that he was already in custody were denied quickly by the pro-coup press later in the day.

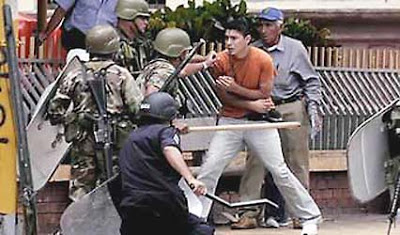

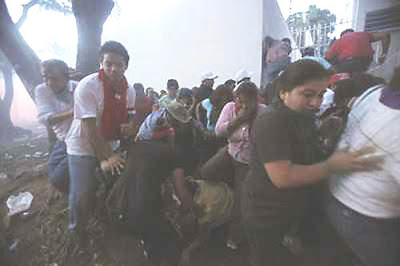

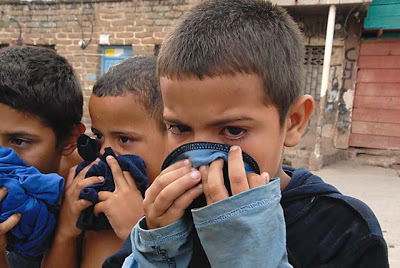

Beginning early Monday, helicopters circled over the embassy and police surrounded the zelayistas but matters became more serious later when the de facto government announced a curfew throughout the country from 4:00 that afternoon until 7:00 the next morning. Some left and some stayed, vowing to spend the night outside the embassy. Around 4:00 Tuesday morning, with around 500 demonstrators still at the embassy, the police moved in with tear gas, water cannons, rubber bullets, pepper spray and, according to some, live ammunition. An unknown number were arrested, many were injured.

The curfew was extended the next day from 7:00 in the morning to 6:00 in the evening. The government closed all the airports as well.

Electric power and water to the embassy were cut off.

Demonstrations against the coup government continued despite the curfew, as they had throughout the three months since the coup, but with increased determination. Soon residents of outlying neighborhoods filled their own streets, in part to oppose the golpista government and in part to voice their rage that yet another curfew was disrupting their lives, already made more difficult by economic hard times and by shortages brought about by the political crisis. The police arrived and the air began to fill with tear gas. There were more arrests and more injuries.

By the end of the day resistance leaders were saying as many as 400 people had been detained at a sports stadium in Tegucigalpa. They reported there had been at least two deaths, one of a child who died of asphyxiation from breathing tear gas and another of a 65-year-old man shot in the abdomen with a police M-16.

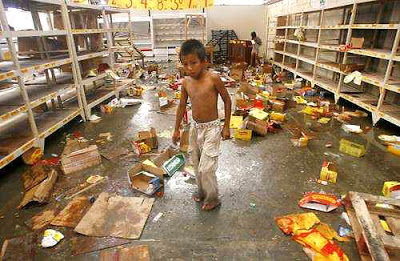

To the surprise of resistance leaders and the de facto government alike, citizens in considerable numbers were not only violating the curfew but were breaking into stores, including a K-Mart, and looting them, taking not just the needed food and medicine the curfew was depriving them of but consumer electronics as well.

By now international condemnation was nearly unanimous, although Hillary Clinton didn’t seem as concerned as most. “I think that the government imposed a curfew, we just learned, to try to get people off the streets so that there couldn’t be unforeseen developments,” she commented.

Micheletti announced that despite fears that he might order an assault on the embassy to arrest Zelaya, he would respect Brazilian sovereignty by allowing him to stay as long as he liked.

The golpista president also announced he was willing to negotiate with Zelaya as long as he agreed to respect the outcome of the November 29 elections. Zelaya rejected the offer as manipulation. Growing numbers of Hondurans had vowed to boycott the elections despite government threats of reprisals for doing so and most other countries had declared they would not recognize them as legitimate.

By Thursday morning, TeleSur was reporting that Zelaya had met informally in the embassy with an unnamed representative of the de facto government. The results of the meeting were not known.

Meanwhile, as of Thursday, the embassy is still without electric power and water, although drinking water has been brought in by truck. Food is being supplied by the United Nations.

[San Antonio native David Holmes Morris is an army veteran, a language major, a retired printer, a sometime journalist, and a gay liberationist.]

The Rag Blog