So Long to the ‘Communist Threat’:

Creekmore Fath, last of a generation of progressive activists

I met Fath during… future U.S. Sen. Ralph Yarborough’s losing 1954 campaign for governor against conservative Democrat Allan Shivers… To win, Shivers campaigned for the death penalty for Communist Party members…

By Dave Richards / August 27, 2009

[This article appears in the August 21 issue of The Texas Observer, Texas’ progressive biweekly that’s been fighting the good fight for more than five decades.]

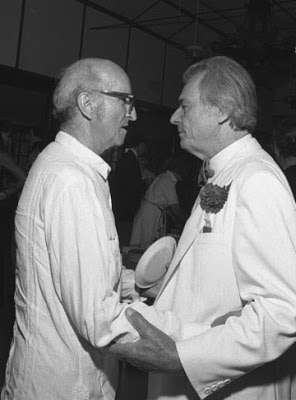

When Creekmore Fath died in June at 93, we’d officially seen the last of an influential cluster of liberal activists who came of age during the Great Depression at the University of Texas. It’s a generation worth celebrating, especially since they deserve plenty of thanks for what modicum of racial justice exists in Texas.

Fath’s often-storybook life (even his name sounds Elizabethan) in many ways exemplified what set apart these UT liberals — Chris Dixie of Houston, Otto Mullinax of Dallas, Maury Maverick Jr. of San Antonio, Bob Eckhardt of Houston, and Fath of Austin. And what kept them together.

I met Fath during my initial foray into politics, future U.S. Sen. Ralph Yarborough’s losing 1954 campaign for governor against conservative Democrat Allan Shivers. The race was close enough to alarm the ruling elite. To win, Shivers campaigned for the death penalty for Communist Party members, along with traditional racist attacks on the NAACP and integration.

By 1956, Texas’ conservative rulers were so worried about the Yarborough threat that they persuaded Price Daniel to abandon his Senate seat and run for governor against the liberal menace. That same year, U.S. Sen. Lyndon Johnson and House Speaker Sam Rayburn decided to challenge the Shivercrats for control of the Texas Democrats. Yarborough forces, including Fath, also mounted a challenge from the left.

I ended up an Austin delegate to the state convention from the liberal wing. We arrived to find ourselves locked out because the Johnson forces controlled the tickets. Some of us got into the building through a women’s restroom window. Others made it to the floor with counterfeit tickets printed up by Harry Holman, a union carpenter from Austin. We scrambled in to find the 200-plus-member Travis County delegation in disarray, equally divided between Johnson and Yarborough.

At one point, the key vote was seating the liberal delegation from Harris County. Travis County delegates had to be polled. Fath counted for the liberals, and Johnson lawyer John Cofer for the other side. At the conclusion of each polling, the two would solemnly announce results that were contrary. Fath had the liberals winning, Cofer had the Johnsonites winning. After polling the delegation three times and getting the same contradictory outcomes, Travis County had to pass without a vote. Even so, the convention was a success. The liberal dynamo from Houston, Frankie Randolph, defeated Johnson’s candidate for the Democratic National Committee. The next year, Yarborough won Price Daniel’s Senate seat in a special election—the first liberal win since Jimmie Allred in the 1930s.

All of this strange carrying-on had its roots at UT in the 1930s. While the university was the heart of intellectual ferment in the state, the Texas Legislature was focusing its periodic red-baiting hysteria on the campus as a hotbed of radicalism. At UT, Fath joined with Dixie, Mullinax, and Herman Wright to reorganize the Young Democrats into the Progressive Democrats. In 1936, Mullinax, Wright, and Dixie (with Fath running the latter’s campaign) ran losing state-legislature campaigns from their home counties. All ran on a Progressive Democratic issue: taxing the extraction of sulfur, a notion floated by another influential liberal, Bob Montgomery.

Montgomery was a favorite target of the red-baiters in Austin. Soon after the election, at the instigation of Johnson friend Roy Miller, a powerful sulfur lobbyist, the Legislature began investigating Montgomery and trying to expose the Progressive Democrats as communists. Along with Montgomery, Mullinax was subpoenaed. “Three of us ran for the Legislature on a program to tax sulfur,” he told the lawmakers, “and were defeated on the charge of being communists.”

Asked during his testimony whether he believed in the “profit system,” Montgomery replied: “I most certainly do. I would like to see it extended to 120 million people.”

The UT liberals all went on to law school and into practice in the early ’40s. Fath and Eckhardt, one of the state’s first labor lawyers, briefly had a joint practice in Austin. Fath went into the army during World War II and then served the aging President Franklin Roosevelt as an aide.

Back in Austin, Fath plunged back into politics. When Johnson ran for Senate in 1948, Fath announced for Johnson’s vacant U.S. House seat as an unreconstructed New Dealer. He and his wife, the daughter of a former secretary of state, campaigned in a car with a canoe roped on top and painted with the slogan, “Fath for Congress … He Paddles His Own Canoe.”

Somehow the slogan didn’t do the trick. Fath finished third in the Democratic primary. Then he went to work, with mixed feelings, for Johnson’s Senate campaign. Liberals like Fath had never been cozy with the future president’s go-with-the-political-wind ideology. “We viewed Johnson with some reserve,” Fath wrote, with appropriate reserve, decades later in an autobiographical essay.

With no Republican Party to speak of, the state’s liberal and conservative Democrats were bitter enemies. Fath and fellow liberals liked to call themselves “loyal Democrats.” Shivers and Daniel preferred to be known as Democratic Regulars who had supported GOP presidential candidates. Johnson often tried to play both sides. With Fath and other liberals reluctantly behind him, he pulled off his infamous 48-vote “landslide” in a Democratic Senate runoff still notorious for its corruption.

In William Roger Louis’s collection of autobiographical essays, Burnt Orange Brittania (2006), Fath opens his often-witty entry by writing, “The history of my life can be summed up by saying that I am devoted above all to two things: the Democratic Party and the University of Texas.”

He might have added liberalism to the list. After failing in his one run for elective office, Fath went on to be a political rainmaker and strategist behind the ’50s and ’60s Yarborough campaigns, and the early ’70s near-misses of Sissy Farenthold for governor. “He could pick up the phone and call,” Farenthold recalls, and “I don’t care what county it was, he’d know somebody there. There would have been no campaign without Creekmore.”

While Fath was working for a more liberal-minded Texas, fellow UT’ers Dixie and Mullinax joined Herman Wright in Houston, representing labor unions in what was becoming an industrial center. Unlike their British counterparts at Cambridge, who wandered off to communism, the Texas liberals mostly remained staunch New Dealers. In 1948, Wright linked up with Henry Wallace and became the Progressive Party candidate for governor. Dixie and Mullinax broke with their friend and supported the Democrats. Shortly thereafter, Eckhardt joined Dixie in his Houston practice. Maury Maverick Jr. practiced law in San Antonio and soon joined Fath in the political arena.

Maury Junior, as he was called, became one of the state’s foremost civil liberties lawyers. Early on, he represented a black prizefighter, Sporty Harvey, in a challenge to the Texas prohibition against interracial boxing matches. Later he sued the state on behalf of John Stanford, secretary of the Texas Communist Party, attacking the search and seizure of Stanford’s library and correspondence in a case that made it to the U.S. Supreme Court. After leaving the Legislature, he spent his later years writing somewhat incendiary columns for the San Antonio Express-News, inveighing against the Vietnam War and later speaking out about the plight of the Palestinians.

Eckhardt, who died in 2001, ended up in both the Legislature and Congress, championing progressive populist causes and becoming a leading advocate for open beaches. (See Gary Keith’s excellent biography, Eckhardt: There Once Was a Congressman from Texas.) Dixie was always a pre-eminent union lawyer. He successfully sued the notorious Texas Ranger, A.Y. Allee, on behalf of Pancho Medrano and others involved in the famous 1966-67 farm workers’ strike at La Casita Melons in Rio Grande City. On the political front, along with Frankie Randolph, Dixie was the driving force behind the Harris County Democrats, the first organization that truly took the battle to the Shivercrats. He was, as founding Observer editor Ronnie Dugger once said of him in these pages, “tough as cactus.”

So was Mullinax. Not long into his career, Mullinax did what was almost unthinkable for the times: He filed a damage suit on behalf of a young black man against the police chief of Nacogdoches, alleging police brutality. The case was lost, of course, but it speaks volumes about these liberals’ tenacity; Mullinax later told me he always carried a firearm when he drove with his client back and forth across East Texas.

These liberals practiced classic coalition politics. Among other accomplishments, they brought together elements of organized labor with historically disenfranchised blacks and Latinos—to the point where, by 1962, it was no longer politically possible to attack the NAACP or the GI Forum, Hector Garcia’s Hispanic organization. When John Connally ran for governor in 1962, he became the first establishment Democrat to court and win segments of this coalition—reportedly at the urging of Johnson.

One other thing to know about Fath, Eckhardt, Dixie, Mullinax and Randolph, along with another great liberal, Minnie Fisher Cunningham of New Waverley: They all helped found the Observer in 1954.

While they never lived to see the Texas they’d worked toward since the 1930s, Creekmore Fath and his liberal cohorts made many previously unthinkable things happen. (And Fath got to witness the once-unfathomable election of Barack Obama before he died.) They opened the way for a progressive future in the state that could be broader and far more influential. It wouldn’t hurt the new liberal Texans to aim for the same kind of integrity and stubbornness that Fath and the “commie liberals” showed.

[Dave Richards is an attorney and author.]

Source / The Texas Observer

Thanks to Steve Russell / The Rag Blog

Thanks for the memories, David, and for saying that we can thank Fath and the others for the "modicum" of racial justice. The drug laws have picked up where racial laws left off, to keep the brown skins in their place.

Fascinating stuff. I'd like to see more from Mr. Richards.

I'm so pleased to see this here! I had the great pleasure of working with Creekmore in Frances "Sissy" Farenthold's first run at the Texas governorship, in 1972. The campaign had "no chance", and practically no money at first, but Creek, as campaign manager, took hold of the young, enthusiastic, inexperienced staff and volunteers at hand and melded us into a lean, mean