For half a century Cuba stood as a beacon for

other countries suffering from poverty and neocolonial domination.

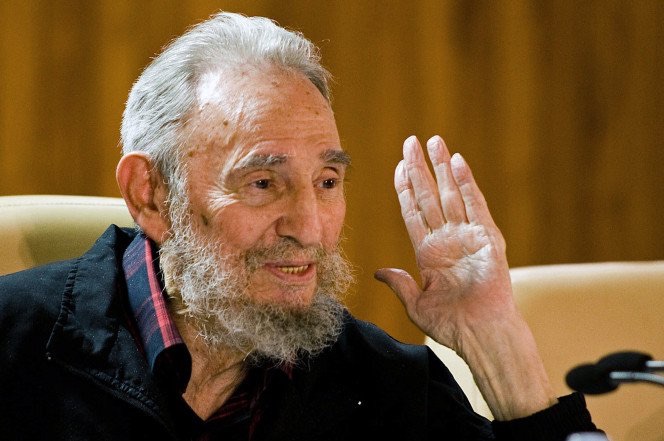

Fidel Castro speaks at the International Book Fair in Havana, February 10, 2012. Image from Cubadebate.

Fidel Castro, longtime leader of the Cuban Revolution, died on November 25th at the age of 90. He withdrew from public office in 2008, when his younger brother Raul took over. Raul has said he will step down in 2018. An era will end, and younger men and women will take the reins of a political process that remains unique in modern times. At the Cuban Communist Party congress in April of this year, Fidel voiced an awareness of his impending death: “Our turn comes to us all,” he told the assembled delegates, “but the ideas of Cuban communism will endure.”

It is unclear how much of Fidel’s vision for his nation will endure in the face of a rapidly changing world with neo-fascist forces gaining ground in so many countries, including our own United States. What cannot be denied is that 57 years ago Fidel led a small group of revolutionaries to victory in Cuba, and against enormous odds established the First Free Territory in America.

The Cuban Revolution stood up to a world power many times its size and strength.

The Cuban Revolution stood up to a world power many times its size and strength, put basic human needs on its agenda, all but eradicated illiteracy, and soon achieved a ninth-grade education for all adults, guaranteed universal healthcare and good free public education from kindergarten through the post-graduate level, worked to provide adequate housing for all, and made full employment a reality. Institutionalized racism and sexism were eradicated and progress was made against their holds on people’s minds and hearts. Citizens discussed and passed new law. Book publishing was subsidized. Culture and sports events were free.

Despite a multiplicity of problems from outside and within, for half a century Cuba stood as a beacon for other countries suffering poverty and neocolonial domination. It is still such a beacon for many. Facing half a century of U.S. economic blockade, the implosion of the European socialist bloc and other impediments, some of these accomplishments no longer shine today as brightly as they once did.

The diplomatic opening with the United States, initiated by Raul Castro and Barack Obama in December of 2014, has brought complex change and promises to bring more: for Cuba a welcome connection to the community of nations, but hampered by a playing field on which it is clear that the U.S. is promoting a change in method rather than in policy. And now, on the eve of a Trump administration, we cannot know how things will go. Still, Fidel and Cuba have given the world a new idea of what justice might look like; this is no small contribution.

But Fidel also gave many of us something

more intimate, more personal.

But Fidel also gave many of us something more intimate, more personal, which is why I think we feel his departure so intensely, like we might that of a beloved father or uncle. For those of us attentive to his speeches of the sixties, seventies, and eighties of the past century, he taught us to think politically — to examine the problems of our generation by moving from the general to the particular and by looking at global issues as they impact our own lives.

Those speeches were lessons in history and economy, given by someone who never talked down to us, always respected his audience. To the end of his life, ill and removed from the everyday business of government, that same mastery of complex situations could be seen in the brief essays he penned.

Fidel taught dignity to generations of Cubans, and generations of those of us who took pride in his courageous stance against foreign domination and for political freedom. He showed us that an impoverished people living in a small island nation could stand up to a fiercely antagonistic enemy many times its size, at the same time improving its education and public health, distributing its material goods more fairly, producing generations of well-trained professionals whose services are appreciated throughout the world.

Fidel redefined what it means to be Latin American and Caribbean.

Fidel redefined what it means to be Latin American and Caribbean, bringing the dreams of Bolívar and Martí into the 20th century. He taught altruism by example; Cuba suffered severe scarcities of material goods, yet was always ready to share what it had with others facing greater crises or undergoing tougher circumstances. Above all, like all great leaders, he taught us to have confidence in ourselves, that despite our problems we could learn and work and move ahead.

I lived in Cuba for 11 years in the 1970s, but only met Fidel once, very briefly in 1968. We were at a large reception with many hundreds of guests. A friend who knew the man took me to where he stood surrounded by other visitors. The year before, in Mexico, I had published an anthology of new Cuban poetry and visual art in the bilingual journal I edited, El Corno Emplumado / The Plumed Horn. To my astonishment, Fidel brought up that publication, referring to several of the included works by name. I tried to imagine what it might be like to have such a conversation with any high level political leader in the United States.

There is always a tendency to romanticize public figures. This is true for the right and the left. The truth is always more complex and much more interesting… more human. Fidel Castro the man has drawn resounding praise and pervasive insult. Whatever one’s opinion, I believe he was a uniquely brilliant strategist and great leader, whose ideas merit our respect and gratitude. Today I weep with the Cuban people. As they say throughout Latin America, Fidel Castro, ¡presente!

Margaret Randall

Albuquerque, New Mexico

November 26, 2016

[Margaret Randall is an acclaimed poet, essayist, oral historian, translator, photographer, and social activist. Her most recent book is Only the Road / Solo el Camino: Eight Decades of Cuban Poetry.]

- Read more by and about Margaret Randall on The Rag Blog and listen to Thorne Dreyer’s October 2015 Rag Radio interview with Randall.