Cold Sun: Austin’s Lost Psychedelic Visionaries

By Patrick Lundborg

[To hear Cold Sun, click here.]

The story of how Austin, Texas was transformed from a sleepy little college town into a world- renowned mecca for rock and country music has been told many times. It’s a neat hippie saga with heroes and martyrs, a few emblematic anecdotes and no loose ends… or so it seems.

But what if there were some loose ends, what if there is a whole tapestry hidden under the Vulcan Gas-into-Armadillo HQ saga as usually told? Maybe the psychedelic era didn’t end with the 13th Floor Elevators, and maybe it didn’t begin with them either?

One of the earliest recognitions of Austin’s new and elevated standing in the music business came with a Chet Flippo article in a 1974 Phonograph Record Magazine. The piece, which is written from an insider perspective, presents an already finalized view of how the preceding 10-year period had played out in Austin and Texas as a whole. By and large, this is the story which has been propagated through subsequent retrospectives. Too large murals of the International Artists label, Vulcan Gas Co, and the few hit or hit-bound artists are painted, while many of the key elements of what constituted a scene – the KAZZ-FM station and the related Sonobeat label, the teen clubs, the legendary Baby Cakes group, the Elevators’ rapid fall from grace in the late 1960s – are missing.

Of course, this is just another case of how the victors, in this case the cosmic cowboys, are allowed to remember what they feel like remembering, and then pass it on for the history book writers. But as we’re beginning to learn, the victory hymns aren’t necessarily the most accurate chronicles, nor the most interesting.

Reaching down into the tapestry of vintage Austin music I found a mysterious strand that seemed to run through a lot of these areas. The thread comes in psychedelic colors, spun into a lizard skin pattern, and forms the previously untold story of COLD SUN.

“There was a mythical Austin that is the root of all subsequent myths about it being such a ‘cool place’. That time was so magical and wondrous that the memory of it still fuels the fake scenes there, today.”

Thirty-five years later Cold Sun founder Bill Miller has few fond memories of the era that brought Austin music to national recognition. According to him and others who were there at the beginning, or 2 seconds after the beginning, it was already going downhill in late 1967 when the Vulcan Gas Co opened. Just like its west coast big brother city of San Francisco, the preceding years of 1965 and 1966 were the true golden age of Austin. This assessment can also be found in Stephanie Chernikowski’s charming 13th Floor Elevators reminiscence, first published in Not Fade Away #1 magazine in 1975. According to Chernikowski, the storm clouds were gathering over the Austin freak scene in mid-1966, a full year before the so-called Summer Of Love.

In 1966 Bill Miller and his friends were too young to be part of the UT-based Elevators circle, yet followed what was going on around the band, and other hot local acts such as the Baby Cakes and the Wig, with great interest. Miller was an unusual teenager with unusual interests that included pet lizards – big ones – and the more esoteric sides of American pop culture, interests that live on to this day. Many thought him to be older than he was, and his active networking in what was then just a small town with a tangible music scene, gave him a good grasp of the goings-on. There were the two local radio stations, KNOW and KAZZ-FM, the latter being the hipper as they did not ban “You’re Gonna Miss Me” but in fact made it a hit. The father-son team of Bill Josey Sr & Jr that ran KAZZ-FM also operated Sonobeat, Austin’s only record label at the time. Over at the Austin Statesman paper there was Jim Langdon, a local Ralph Gleason who wrote excitedly about the new “psychedelic rock” of the Elevators. The huge UT campus and related Ghetto scene supplied a bohemian undercurrent to the city, as it had for several years. But Austin was still just a local scene and noone thought of comparing it to the rich, legend-filled musical heritages of Houston and San Antonio.

Too young to have been part of the mid-1960s teen music explosion Bill Miller and his guitarist friend Tom Mcgarrigle formed their first band in 1968. The band was called Cauldron, and apart from Miller and Mcgarrigle featured John Kearney, who had played drums with Roky Erickson in his pre-Elevators band, the Spades. Cauldron soon changed their name to AMETHYST, and played at the local “I.L Club”, which was the first psychedelic underground club in Austin. The small club, named after and run by Ira Littlefield, was located in a rough East Austin (the black part of town) neighborhood and had a sign upfront that read “Famous Beatnik Bands, Nightly”. Conqueroo played there several times. Some Amethyst recordings exist from the I L Club; these remain unheard but it appears that even at this early stage the band relied solely on original material such as “See What You Cause”. During this period there was some member shuffling including a succession of lead vocalists who failed to work out right. Drummer John Kearney has commented that Miller’s long, complex songs required plenty of rehearsal, one reason for him to later leave the band.

Already at this stage Bill Miller had found the instrument that he would continue to favor throughout his career, the autoharp. Autoharps were unusual but not unique within rock music at the time; some folk-inspired bands like the Lovin’ Spoonful and the Charlatans used them, or at least posed with them for pictures. But in a development similar to how Tommy Hall had turned the concept of “jug”sounds upside down with the Elevators, Miller decided to take the autoharp into places it had not been before. The instrument was adapted and rebuilt into a fully electrified unit, and Amethyst’s music was arranged to accommodate and make full use of the unearthly sounds of the electric autoharp. Most people have heard Miller’s instrument as used on the famous Roky Erickson & the Aliens recordings from the late 1970s, but 10 years earlier it resounded around local clubs in Texas.

While Amethyst was building up a repertoire and re-shuffling its members, the Austin music scene was changing rapidly around them. Despite releasing their masterpiece “Easter Everywhere” album in November 1967 and playing Vulcan Gas the same month, local heroes the 13th Floor Elevators had been going downhill ever since returning from California in late ‘66. The later line-ups of the band were arguably the best in terms of musicianship, but a lot of people were lamenting the loss of energy and excitement from early 1966. Many other teen club bands from the pre-hippie era that had spawned the Elevators were also gone or disappearing, and almost none managed the transition into the “progressive” times of the post-Sgt Pepper late 1960s. Golden Dawn, who partook in the local LSD revolution as “Elevators protegés”, fell apart shortly after their brilliant I A album had been released. Bill Miller recalls that Dawn key figure George Kinney stopped by at a few Amethyst rehearsals. The Baby Cakes merged with the Wig into the heavier Lavender Hill Express and their former bands were soon forgotten. As everywhere else harder drugs entered the picture and rock music itself was splintering off into various directions. From the very beginning Vulcan Gas Co booked new local bands that represented these changing directions, such as the Conqueroo (S F Bay Area acidrock) and Shiva’s Headband (embryonic country-rock). There was also a constant back-n-forth between Texas and San Francisco, as many bands tried their luck in the Bay Area only to discover it jam-packed with starving rock bands.

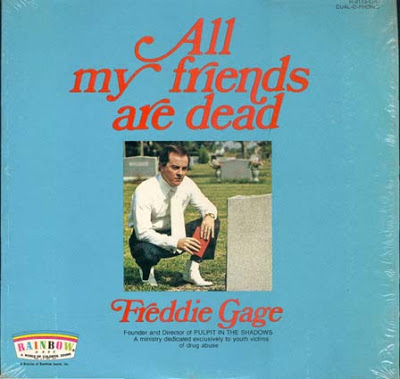

Bill Miller’s Amethyst weren’t terribly impressed with this new direction and scene, which would ultimately lead to the grand 1970s days of the Armadillo World Headquarters. Amethyst was a young band, but the members had been around in the days of genuine excitement. Rather than picking up steel guitar, or get a speedfreak guitarist that could imitate Johnny Winter, the band continued along their specific vision as represented by its two constant members, Miller and lead guitarist Mcgarrigle. The two had plenty of ideas and ambition, and for a while ran their own rock club at Jubilee Hall down in Houston (maintained by notorious preacher Freddie Gage). After giving up trying to find a lead singer they settled on sharing the vocals between them, and soon Miller handled the majority of them. Apart from the Elevators heritage, which is obvious in the band’s subsequent recordings, Miller kept abreast of developments in other parts of America and added the Doors and Velvet Underground to his list of influences. Velvet Underground would play Austin in 1969 after Vulcan Gas had somewhat reluctanctly booked them; the shows were a success and another indication of something else cooking locally, apart from the country and blues mutations. Miller was there, naturally, and had a conversation with Lou Reed backstage regarding the 13th Floor Elevators.

“If it ain’t peyote, it ain’t from Texas”

Beyond the college student and redneck clusters there were strange developments in and around Austin at the time, and Amethyst/Cold Sun were connected to many of them. Unusual characters crowd their history, such as the band’s friend and future Roky Erickson exorcist/bodyguard Winston “Wink” Taylor, member of an esoteric Christian splinter church led by Father Robert Williams – this congregation later counted Roky’s mom Evelyn among their members and assembled in a church that once served as a rehearsal space for the Elevators. Taylor and his friends used to live in the Serpentarium, an abandoned snake farm outside town. This circle included soon-to-be Cold Sun bass player Mike Waugh, and the enigmatic Johnny Love, a Hollywood-style singer and dope dealer who many locals thought was a government agent. For a while the Snake Farm residents had a band going called Alpha Centauri. On the enemy side there was the notorious Captain Harvey Gann, chief narc officer in Austin, known to always wear a bright red suit when conducting a raid. Gann and his team watched the Elevators and other local rock bands very closely.

Bill Miller himself still had plenty of space to allow his special interests to grow, and in fact made the local papers when his huge tegu lizard ran away and was put into a dog pound, from which it promptly escaped. Other Miller projects included building a complete Dr Doom (the Marvel comic book villain serenaded by the Elevators) costume, although it did not progress beyond a completed metal glove. One interest that would have direct impact on Cold Sun’s music was ancient Egyptian mythology, as heard on the “RA-MA” track from their Sonobeat tapes, an 11-minute epic that also invoked Lemurian elements. And psychedelic drugs were of course everywhere, as they had been in Austin long before the Elevators started handing out free LSD at local gigs. Miller recalls that “a wider cross section than one would imagine did peyote. The 60s beatnik-peyote scene seemed to know no beginning – it had been among the hip as long as the hip had existed since way before acid was invented. It was legal and could be purchased in cactus shops and plant stores. Things were actually more cool before acid appeared.”

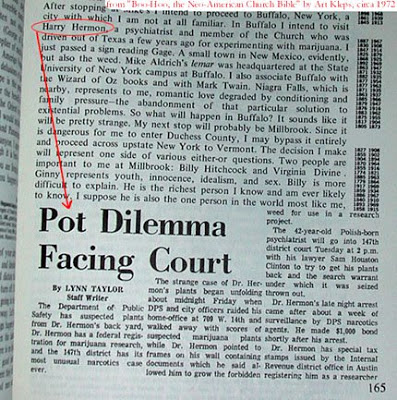

An official secret of the town was Dr Hermon, a Viennese immigrant who the straight Austin medical establishment referred to as “Crazy Harry”. Hermon had a Federal licence to prescribe and administer LSD, marijuana and mescaline/peyote. The Austrian psychiatrist carried a jet set air about him and was into concepts like hypnotism, nude therapy and psychedelic evolutionary therapy. His eccentric image and non-conformist behavior put him in contact with the Austin music underground, which he supplied with psychedelic drugs for several years. Captain Gann and the narcotics squad were aware of this, but Dr Hermon’s medical licence made him difficult to bust. Hermone’s rapport with the rock musicians was such that he was appointed doctor for Roky Erickson when Roky was staying at Holy Cross Hospital in 1968, recovering from a nervous breakdown. Unsurprisingly, in this case Hermon made sure not to involve the patient with drugs. Gann and his narcs later managed to crack down on Hermon, who was forced to leave Austin in a haste.

John David Bartlett, a local musician who worked with the latter-day Elevators and was signed to International Artists recalls hanging out with the Amethyst members: “We had many late fuzzy evenings at Bill’s tiny apartment at the base of Castle Hill. There was an old white wood frame building that rambled up the hill. It had been divided into tiny efficiency apartments for the more adventurous of Austin’s scene in those daze and had stairs that went up the outside along the hill. It was like an extention of the old Texas Ghetto, with a younger crowd. My house up on Blanco at the top of Castle Hill tended to attract a lot of jam monkeys. That’s where we first met Bill and Tom. Tom was such an intense and great guitarist. Bill’s first band didn’t attract as much attention among my crowd as Cold Sun. I think I heard them only once. But in 69′ we all were cut loose from the mooring and on a fairly consistant high. I remember one night best. Sitting at Billy’s apartment and he played a new song. Hard dischordant autoharp as Bill screamed ‘we live beneath Spider City’ [from “South Texas”]… I’ve got to underline the way Tom looked in those daze. Dark and beautiful. And Billy all in black.”

Fred Mitchim, member of the same young Austin scene, recalls his first encounter with Miller and McGarrigle at the Castle Hill freak complex: “I was listening to my friends talk about how Bill was so relieved to have his own place so he wouldn’t have to keep his stash in a jar in the back yard any more. This story was my first impression of Bill moments before I met him for the first time. As we headed up the pathway I heard Cold Sun for the first (and most memorable) time. I was struck by the originality of these psychedelic yet also dark songs. And of course Bill’s electric auto harp against Tom’s searing single note double picking fuzz box echoplex leads. Really nice. When they finished my friends introduced me and I remember noticing Bill to be the first “dressed all in black” person I had met. Back then 6 foot tall Tom would wear no shirt with a orange tuxedo tails coat, red bell bottoms, blue rubber health food sandals, with 3 feet of black hair.”

Around the time of the Velvet Underground shows at Vulcan, Bill Miller hooked up with another of his sources of inspiration, former Elevators drummer John Ike Walton, who had returned to Texas after a spell as a session musician in California. The newly recruited Amethyst bass player Mike Waugh introduced John Ike to Miller and the band. It seems Walton was on the verge of becoming a member of Amethyst, replacing Roky Erickson’s old Spades drummer John Kearney in an ironic twist, and while he soon bowed out he would play an important part in the band’s evolvement.

From his Elevators days Walton was familiar with Bill Josey Sr who ran the local Sonobeat label, and he suggested that Josey would check Miller and Amethyst out. After having sold the KAZZ-FM radio station in the Fall 1967 to focus on their record label, Josey Sr and Jr had released a string of interesting 45s with local artists, including the only record that the legendary Conqueroo ever would release, as well as excellent singles by the Sweetarts and non-Austin band the Thingies. The label’s story has been chronicled in some detail in Not Fade Away #2, which oddly contains no mention of Cold Sun. Beyond a fairly impressive release catalog, Sonobeat took special interest in the technical aspects of record production, and in fact claimed to be the first label anywhere to feature a mono compatible “solid state stereo” sound on their early 45s. Around this time – 1969 – Josey was working with local band Mariani, named after and lead by their drummer but noted mainly for teenage wiz kid lead guitarist Eric Johnson, as well as with Johnny Winter whose reputation was already growing beyond Austin’s borders in the wake of a Texas music feature in Rolling Stone magazine.

Bill Miller remembers the first demo session, as almost everything else connected with the band, very clearly: “John Ike told Josey about me and he asked Mike Waugh to set up a meeting. I think the first time Josey heard me was in the studio. Mike and John Ike had only heard me play solo, through an amp at my house. Josey had me record a long demo – about 15 or 20 songs with me singing into a mic in the drum room and with the harp pickup plugged directly into the board. That first demo was supposedly a song demo. I recorded it in one night. That was when Josey`s studio was still in the basement of his house. During the recording of that first demo, he phoned Vince Mariani and had him come over. I saw him from the booth, staring at me and smirking. I emerged from the booth right after recording ‘Here In The Year’ followed by ‘God Is A Girl’ and met Vince, who said to me first off, ‘Man, you`re really a freak’”.

Bill Josey Sr was sufficiently impressed with Miller’s demo recordings to offer the band a development deal, where they would work on their music in order to produce recordings that could be pitched to major labels. Sonobeat made demo LPs of Mariani and Johnny Winter following the same principle, as well as a little known folk-oriented artist named Bill Wilson. When John Ike Walton did not join the band they brought in drummer Hugh Patton instead, and with a complete line-up in place they were ready for the recording studio. One final question that needed to be solved was the band’s name, however – they weren’t really Amethyst anymore, and in lack of a name Josey would refer to them as “The Bill Miller Project” for the time. About halfway into the sessions the band came up with COLD SUN, which would stick for the rest of their career. The band still used the Amethyst moniker for a few live gigs around this time.

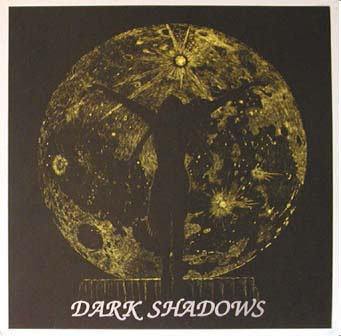

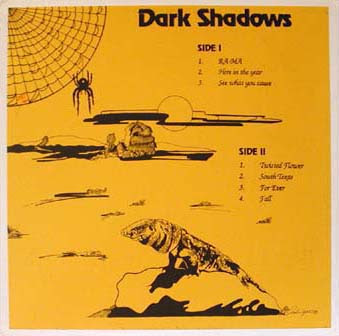

As with many things in their history, the name “Cold Sun” is enigmatic. The 1989 retrospective album on the Rockadelic label that first brought the Sonobeat recordings to light didn’t even appear under that name, but as “Dark Shadows” which is the title of a popular 1960s mystery TV series. In the liner notes Miller denied ever having been in a band called Cold Sun, and suggested that they had always been called Dark Shadows. However he had referred to the band’s real name in a 1976 interview, where he mentioned that before playing with Roky Erickson in the Aliens he “spent seven years developing the electric auto-harp with a band called Cold Sun”. The name itself is derived from the legends of MU, made famous by the writings of Col James Churchward and more recently by the great 1970s rock band of the same name, led by Merrel Fankhauser. MU and the Lemurian mythology was popular in Cold Sun circles, although Miller says that he tried to come up with an even better band name later on.

After using a local club for recording, the Sonobeat label had set up their own recording studio in the basement of the Joseys’ house. The early stages of the Cold Sun project were located to this basement studio, but the material actually preserved on tape was made at yet another Sonobeat studio in a building on North Lamar that also housed the KOKE radio station, owned by Austin’s then-mayor Roy Butler (ironically, KOKE was Josey’s old KAZZ-FM restructured and renamed). This is where all known Cold Sun recordings were made. Miller estimates the total time for the project to roughly 6 months, including work tapes, demos and actual recording sessions. All of the material had been written prior to the Sonobeat deal, but went through various changes and upgrades as the sessions progressed. There were also a few songs from the first demo tape that were discarded along the way, among them “God Is A Girl”, “Graduation Day” and “Do The Ray” which were all written by Miller – the latter being the band’s “dance tune”, inspired by Roger Corman’s “The Man With The X-Ray Eyes” – and “Mind Aura” and “Shifters” by lead guitarist Tom Mcgarrigle. Vince Mariani and Bill Josey both suggested that Miller do all the lead vocals, which may have been the reason that Mcgarrigle’s tunes weren’t used. Incidentally, Cold Sun bass player Mike Waugh was well familiar with Josey, having been used as an in-house session bassist on many Sonobeat recordings before joining the band.

Despite the creative and seemingly unproblematic nature of the sessions, Miller recalls that “Bill Josey did not understand where we were coming from musically. We couldn`t explain to him what`s happening, so I explained to him that Tom and I are simply, ‘Lou Reed fans’. He didn`t understand that, either.” Josey may have had a greater input on the technical aspects of recording Cold Sun than the actual music, and as Miller remembers him “Josey was indeed a wizard – maybe the closest thing that Texas had to a Joe Meek. Josey invented the Sonotone Black Box – a mysterious device, some sort of compressor. I do remember Eric Johnson recording with the Black Box , but he only used it to a minor degree. Johnson did not understand it. Neither did I. I played through it, too, to try it out, but never recorded with it.” The highly unusual autoharp likely ticked Josey’s interest, as there were no precedents for how to record it. As it turned out the autoharp was fed directly into the board on most songs, as was the bass. The Cold Sun recordings were originally intended to be in quadraphonic sound, one of Josey’s pet interests at the time.

In addition to musical arrangements, a lot of work was put into the lyrics. Miller isn’t very proud of them today, but they still stand head and shoulders above the usual hippie fantasy nonsense from the era. Every song has several lines that stick in memory the way well-written rock lyrics do. The vast majority of them were written by Miller, but input and inspiration also came from Mcgarrigle and band friend Winston Taylor. Another lyric collaborator of Cold Sun was Sonobeat associate Herman Nelson, a square-looking middle-aged man who behind his façade was known as a local mystic and white magician. Miller recalls the source for the tracks like this:

“Whatever ideas other than Colonel Jim/Mu stuff came from me, Tom and Winston. ‘Ra-Ma’, ‘Fall’ and ‘Twisted Flower’ were very much Churchward influenced. ‘South Texas’ and ‘See What You Cause’ were not, really, and ‘South Texas’ was mostly a 100% psychedelic anthem drenched in peyote. ‘For Ever’ and ‘Here In The Year’ were 100% me . Only ‘Fall’ and ‘Ra-Ma’ contained lyrics by the other 3 people.“

A numerological infatuation shared by Josey and the band members influenced the Cold Sun lyric writing and recording, according to Miller:

“Josey was superstitious. He believed that the Johnny Winter album’s exact track length was a lucky number. It was 43 or 45 minutes and – oh, I forget how many seconds. You can check the Johnny Winter length – you will find that it is exactly the same length as the Cold Sun album – exactly, to the second. ‘Ra-Ma’, and ‘Fall’ had to be made longer to fit that time frame and a song that Tom wrote was dropped at Tom`s insistance; he was as superstitious as Josey and prone to suggestion in those areas – fearful of certain numbers. So was I. I was desperate for more lyrics and am afraid those weak lines were not very real, just whatever would rhyme. I wrote the weak lines, myself. It was still a bit short in length, so Josey got the idea to add the wind chimes thing at the end of ‘Ra-Ma’.”

The running order presented on the 1989 Rockadelic issue of the Sonobeat tapes differs markedly from how Miller and Josey had envisioned the album back in 1970. This is their original, intended track order:

1.- “South Texas” (Miller)

2.- “Twisted Flower” (Miller)

3.- “Here In The Year’ (Miller)

4.- “For Ever” (Miller)

5.- “See What You Cause” (Miller)

6.- “Fall” (Miller, Taylor)

7.- “Ra Ma” (Miller, Mcgarrigle, Nelson)

While there are pros and cons of both structures, one could opine that “South Texas” would have made for an extremely strong opening, and that the album as a whole would build to an appropriate climax with “Ra-Ma”, as originally planned.

Regarding the musical re-arrangements during the sessions, Miller recalls that:

“Only ‘See What You Cause’ remained the same, even the technique of having Tom play bass and the bass player play lead guitar. Tom had no intention of playing bass, but it worked well on that song to do it that way. He and Mike both were cool about that. ‘Fall’ was the same musical passages as before, but, with new words added and the old lyrics 100% discarded – except the part about Dodge – that lyric was the same as the older version. The harmonica was also new in the ‘Josey’ era. In that photo of Cold Sun, you can see a harmonica holder attached to the top of the autoharp if you look closely. It was a harmonica holder with the neck piece removed, which I`d slide into place through brackets on the side of the harp – I would swivel the harp to ‘center’ and use the harp itself as a holder – while playing it – playing both instruments simultaneously.”

The vocals on the Cold Sun album have confused people as there seem to be two different lead vocalists, sometimes switching parts from one line to the next. The truth is that both vocalists are Miller, who in spite of not being a natural vocalist shows a remarkable versatility on the tracks – he will move from a dark, Jim Morrison-influenced vocal style into a piercing, Roky Erickson-like acid-punk voice seemingly without effort, and without ever revealing what is his “true” style. The vocal harmonies were handled by Mcgarrigle and Waugh, with Waugh given two lines of lead vocals on “Twisted Flower”; a source of amusement during the sessions, according to Miller:

”I really wanted Mike Waugh to sing the whole song and he wanted to, very much. However, he was not as good as me on that song as lead vocalist , except for those 2 lines. Bill Josey said, ‘He sounds like Jerry Lewis, and I don’t mean Jerry LEE Lewis!’. Josey later named the middle section (‘Yes, I receive the calls …’) the Jerry Lewis bit. In vocal sessions, Josey would say, ‘OK, lets try to improve on the third line of the Jerry Lewis bit.”

Here are some other Miller comments on the Cold Sun tracks:

Here In The Year — “Regarding the end section Josey said: ‘That is so beautiful. Surely you aren`t really going to let Tom put NOISE over that?’. Later, I laughingly told Tom. His reply was, ‘Well, cry me a river’. That song was not a Peyote song, though. It was a prediction of the Internet – but with links to the Ethernet. The original verse was ‘Here in the year 1969’. Lame, huh? Well, it was 1970, finally, and counting – and doubts increased about Josey cutting the ‘Columbia’ deal – I was motivated to alter the lyric a bit.”

Ra-Ma — ”All bass you hear in the beginning ‘dreamy’ segment is my thumb doing bass lines on the autoharp as I play the other strings with my fingers… Does the harmonica RUIN it? Does it help? I think it`s good on Ra-Ma. Josey liked it on that song. He smiled. I got it on the first take. I play lead guitar on the first part with vocals, ‘Crocodiles line the banks …’ etc. I wrote that guitar part and did not want Tom to waste time on it – he was too busy with other parts. Later, of course, he learned it for the live performances. Does ‘Ra-Ma’ sound better or worse, now that you know it was about Mu ?”

Fall — ”Herman Nelson wrote far more for Josey than I realized. I had forgotten that he wrote the melody and lyrics to Mariani`s ‘Re-Birthday’. I remembered a couple of lines he wrote for Cold Sun – ‘Fall’. ‘Willow binds like steel/from your lotus wheel’ Actually that was written for a different song – If I had used his words in the song he wrote it for, you would hear, ‘You may never see what you cause/You may never see what you cause/Willow binds like steel/from YOUR lotus wheel/from YOUR lotus wheel’. Funny, huh?”

See What You Cause — ”It was an obvious tribute to Roky, whom I had never met at that time. I was good at ghost writing for Rok even back then. That came in handy as I arranged ‘Bloody Hammer’, ‘Night Of The Vampire’, ‘Two Headed Dog’, and others.”

South Texas — “Inspired by a weekend in South Texas with 2 girls from Corpus Christi and a big bowl of peyote salsa and a drive-in Mexican restaurant with these great big fried tortillas. There was a motel crawling with these tiny geckos. Geckos have voices. Peyote is more AUDIO oriented than any other drug, as far as I know. Tom Mcgarrigle sounded like a Gecko with his guitar, at times.”

Twisted Flower — “The ‘Bass’ solo at the beginning is actually the autoharp. The drum clicks start it off and then the autoharp comes in with the heavy booming autoharp bass strings playing the bass solo, then Mike Waugh decends into what is a brief ‘Bass duet’ before the guitar and harp come in with the higher stuff.”

The basic idea for the Cold Sun studio project was that Josey would pitch the finished recordings to a major label, Columbia being the one most frequently mentioned. The method of pressing vinyl demo discs in a limited run was going out of fashion, as modern tape techniques simplified the demoing process. The Mariani LP from 1969 was the last of the Sonobeat vinyl demos, and as the Cold Sun sessions were wrapped up in the Spring 1970, stereo cassette and quarter track dubs of studio tapes were used for presenting the material. This is the reason no demo LP or acetate exists from the original sessions (note: the infamous Cold Sun acetate dates from a later stage, detailed below). Unfortunately, Sonobeat’s financials were under pressure at this point and Josey may not have been able to put enough weight behind his Cold Sun pitch. The label had scored a substantial PR hit with Johnny Winter, whose “Winter” LP from early 1969 (later re-released as “Progressive Blues Experiment” on UA) was recorded with Sonobeat before Winter signed his huge deal with Columbia, but it appears that little or no profit from it ended up with Josey. In the case of Cold Sun it’s possible that the band’s unique brand of psychedelia did not match what record labels expected from an Austin band at the time. In short, no contract was signed, and Sonobeat itself went into low-profile.

Bill Josey Sr kept working with recordings of various local artists in a new studio outside Austin before becoming ill in 1976 and passing away shortly after. His son Bill Josey Jr who had been involved with the label and the KAZZ-FM station, using the on-air DJ alias of “Rim Kelly”, showed some interest in reviving the label in the 1990s, but nothing has yet come of these activities. Bill Miller remembers Josey Sr fondly. “I lost track of Josey news around the time I began to help Roky develop his songs, a few months before BliebAlien did local shows – must have been circa late 1974. I don`t think Bill Josey did much more before his fatal illness, but have wondered what he did in that period. Things were moving so fast. I regret not visiting Bill Josey again. He was a great man, gave a lot to the Texas scene.” Bill Josey’s and the Sonobeat label’s full story still remains to be told.

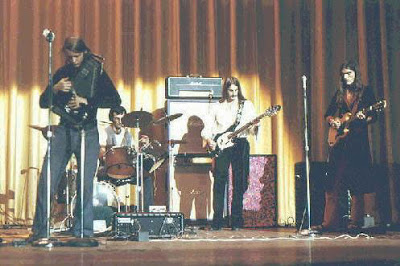

The Cold Sun saga was far from over, however. The band kept working on their material and gigging locally now and then. Bill Miller recalls several new tunes from the post-Sonobeat era, such as “D.J.`s Locker”, “The Worldwide Voice Of James” and “PayOla”. A live recording from the time includes “Out Of Phase”, “Where The Shadows Lie”, and “Live Again”. Most of these were written by Miller, who was the band’s driving force at this stage. Tom Mcgarrigle actually left the band for a period, but came back shortly after. Bass player Mike Waugh, whose musicianship is still held in high regard by Miller, unfortunately left the band and had to be replaced – a very daunting task according to Miller. After another bass player didn’t work out Waugh was replaced with a Mike Ritchey, and with Mcgarrigle back this was the Cold Sun line-up for the rest of the band’s career. The on-stage photo of the band from the Palmer Auditorium (where Bob Dylan had played a legendary show back in 1965) shows this last line-up.

Fred Mitchim recalls the live Cold Sun like this: “On stage Bill would be slumped over his harp and Tom would be standing real straight like Cipollina. My memory of how they were perceived by the locals is from the 2 or 3 times I saw them play. In the clubs it went right over most people’s heads. At this time I’m positive no one had ever been exposed to anything like Bill’s wide eyed scary psychedelia. At the high point of each set Bill would turn a fuzz box on his harp and play it with a kitchen knife. As I was saying… Zoom… right over their heads. I don’t remember them playing out that much but it seems like they we’re always slaving over the album they were recording so if you were not a local musician you might not know much about them and back then almost no one was allowed to hear the recordings.”

JohnDavid Bartlett has similar memories: “The ‘over the head’ reference is true. There weren’t that many live Cold Sun shows as I remember. But at the ones I saw, when a song would end the musicians in the audience would howl, while the rest looked like the audience in “The Producers” at the end of “Springtime for Hitler”.

The band was never a success locally. It appears that their music simply was too far removed from what was happening around Austin, the parallel infatuation with country and blues “roots” music being all the rage, and the city’s growing national exposure giving increased credence to that orientation. Cold Sun built partly upon the 13th Floor Elevators, but the Elevators were dead and buried in 1971 and people wouldn’t even admit having once liked them. Their other musical influences were urban and intellectual, and wholly alien to what was going on. As Miller recalls, “We played shows that were a faithfully reproduced live version of the album – but better. We were not that serious about playing in Texas, but would have played more. When you hear that album, whatever it is that makes you like it, you should understand that the same thing that makes you like it served to make clubs and brats in Austin NOT like it”. They weren’t without supporters, though: “Vince [Mariani] never missed any show we did. We reminded him of some lost element from childhood – carnivals. After one show he said, ‘You guys sound like you just walked out of a space ship’”.

The band soldiered on into 1973 with Miller busy learning the ropes of the music industry. Tom Mcgarrigle left the band permanently, and Miller relocated briefly to Memphis and worked on his business network. Cold Sun was on the back burner, but another and equally interesting phase was just around the corner. Some time earlier mutual friend Winston Taylor had introduced Miller to Roky Erickson, who had been released after 3 years in Rusk State Hospital and was back in Austin. Miller recalls an early encounter with Roky: “One day, I entered Roky`s house and he had allowed a pile of wax candles to melt into the center of the shag carpet until the carpet became the wick of the giant candle, burning brightly. Roky was sitting on a large chair smoking a J. A man with long hair, glasses, and white robes was at his feet. Roky was barefoot and the man was washing his feet in some special ceremonial golden platen – presumably filled with Holy Water? The man used a special cloth and every motion seemed like some specialized routine, some ritual.”

Roky Erickson’s career was essentially back to zero at this point. There were some one-off Elevators reunions, but not much else. Roky had a network of friends who helped him through his Rusk period and after, among them Patrick Mcgarrigle, younger brother of Cold Sun’s lead guitarist. In an effort to revitalize Roky’s rock’n’roll career Patrick Mcgarrigle wanted to put a band together, and as part of this Bill Miller was contacted. Bringing in “the only two musicians in Texas I could trust”, Mike Ritchey and Hugh Patton were selected for the rhythm section, and so BLIEBALIEN was born. As Miller points out, this band was essentially Cold Sun under a new name, with Roky on guitar instead of Tom Mcgarrigle. Roky had written a massive number of songs – perhaps as many as 200 – while in Rusk, and the BliebAlien project aimed mainly at arranging these for a rock setting. Live gigs weren’t a priority, but as a local show at the Ritz unexpectedly was booked, Miller was called in to join the band. This marked the beginning of a phase that later would lead to Roky Erickson & the Aliens being formed, an outfit who should need no introduction. The BliebAlien and Aliens years lie outside the scope of this article, but will hopefully be covered elsewhere. According to Miller, it is “even stranger” than the Cold Sun saga.

This isn’t quite the end, however. Sometime around 1973 Cold Sun bass player Mike Ritchey had taken the Sonobeat master tapes and had an acetate made from them. The main reason was that he wanted to be able to replay the recordings – on which he doesn’t actually play – on regular hifi equipment. As far as can be determined, only 1 single acetate was made, and remained in Ritchey’s possession. At one point he played it for Roky Erickson, who was surprised as he hadn’t heard of neither Cold Sun nor Bill Miller’s songwriting capabilities. As Miller tells it, Roky confronted him after hearing the acetate:

ROKY : “Now, Bill, who is the writer in this band?”

BILL : “You are, Roky. Why would I want Bill Miller for a writer when I could have Roky Erickson? Do you think I`m stupid?”

Soon after this incident the Cold Sun acetate and the band itself disappeared off the face of the earth; the only trace of them anywhere was a brief 1976 interview reference by Miller. As it turned out, it would be 15 years before anyone heard of Cold Sun again.

“At one time my greatest fear would have been the thought of anyone hearing the old Cold Sun recordings.”

In 1989, Rich Haupt and his partner Mark Migliore of the Dallas-based Rockadelic record label were approached by Michael Ritchey, who knew Migliore since before. Ritchey wanted them to hear something with his “old band”. As Haupt recalls it,

”It was a 3 or 4 song acetate labeled Cold Sun…..needless to say when we listened to it we were blown away. Michael got Mark in touch with Bill Miller and he tried to work out a deal to release the material. After many conversations, Mark gave up and concluded that these songs would never be released as Bill was pretty adamant about NOT releasing them. I asked Mark if I could give it a try and after many hours on the phone I think I convinced Bill that his material was GREAT and that it would be a shame if no one got to hear the LP. Bill finally agreed but there were some details that were difficult to work out. The biggest obstacle was the name of the band. Michael Ritchey, who was responsible for getting the ball rolling (although he was in the band AFTER the recordings) insisted the name of the band was/should be Cold Sun. Bill on the other hand insisted on Dark Shadows, which was something he made up years after the band was defunct. I did my best to compromise and printed both “names” on the cover. The second big issue was the inserts that went in the LP. Bill wanted his extensive notes while Michael wanted a more simplistic, coherent insert. Again I tried my best to compromise and put Bill’s notes in 1/2 the LP’s and Michael’s in the other half. There is no question that this is the best LP we have had the privilege of releasing, and hopefully Bill is glad that it ultimately has worked out the way it has. I could have pressed MANY copies of this both on vinyl and CD over the years but have stuck to my word of only releasing 300 copies.”

It should be pointed out that the acetate was not the source for the Rockadelic reissue, but rather dubs from the original Sonobeat master tapes, which were still in Miller’s possession. The acetate only features about 2/3rds of the material on the Rockadelic record, and is in pretty worn shape — a fact that didn’t keep it from selling for a whopping $10.000 on the record collector market recently. The actual deal reached between Rockadelic Records and Miller was unusual:

“All Rich Haupt paid me for the album was: A giant billboard sized picture of Simone Simon. He said – “If you let me release this, I will pay you. How much money do you require ?” I said, “I would require a giant billboard sized picture of Simone Simon, so I can erect a proper shrine for worship.” Rich said , “Who is Simone Simon ?”. I told him: Star of “Cat People”, the icon star of Jacques Tourneur, who was the David Lynch of the 1940`s. Jacques Tourneur directed “I Walked With A Zombie”. So, Rich got me a giant picture of Simone Simon. And I sent him the Josey reel dub from the Josey master.”

The album front cover was designed by Rockadelic, while Miller suggested putting the tegu lizard on the back. Apart from the liner note insert, the package included a color on-stage photograph of the band. The release was an instant success among fans of underground psychedelia, and the 300 numbered copies sold out very quickly. Despite having been bootlegged (in inferior sound and without inserts), it now changes hands for over $100. Even after the album was released Miller was unimpressed with his old recordings, and would not discuss the Cold Sun era. It would be several years and much prodding from fans across the world before he recognized that they may have great value, even if they failed to wow the world back in 1970. As of this writing plans for a CD release of the Sonobeat masters, and hopefully some bonus live material, are in progress. Meanwhile, Miller – who today is known as Billy Angel – has entered a third, or fourth, phase in his career, now as autoharpist with the Blood Drained Cows, a Southwestern rock band that also features members from 1980s legends the Angry Samoans. The Blood Drained Cows are gigging frequently around USA and have a new CD out, titled “13”. On stage the band plays a 13th Floor Elevators cover, thus closing a circle that began in Austin 1966.

© Patrick Lundborg and Lysergia.com, 2003-2008

This article has also appeared in print in MISTY LANE magazine #18, 2003.

REFERENCES

1. “Texas Rock & Roll Spectacular” by Chet Flippo, in Phonograph Record Magazine, March-1974

2. 13th Floor Elevators article by Stephanie Chernikowski, in Not Fade Away magazine #1, 1975.

3. Sonobeat article by Doug Hanners in Not Fade Away magazine #2, 1977. (Online with Bill Josey photo at www.scarletdukes.com/st/tm_aussonobeat.html)

4. Texas rock article by Larry Sepulvado and John Burks in Rolling Stone, issue #23.

5. Brown Paper Sack magazine #1, edited by Andrew Brown, 1997.

6. “13th Floor Elevators – the Complete Reference File”, book by Patrick Lundborg, 2002. lysergia_2.tripod.com/elevRefFileMain.htm

7. “Journey To Tyme”, discography of Texas music by David Shutt, 2nd edition 1981.

8. The Ghetto website, with Austin 1965-69 article by Gerry Storm.

9. Rockadelic Records website, with Cold Sun audio clip

10. Blood Drained Cows site with links to Billy Angel’s site.

To discuss and learn more about Texas music from the 1960s and early 1970s, visit the Texas 60s Refuge.

Source / Lysergia

Many thanks to Patrick Lundborg and Thomas McGarrigle / The Rag Blog

It is so cool to hear of Captain (I think it is Harvey) Gann. The Chicano’s called him “El Ganso”- the goose. He was a nice man at the time but scary.

In 65-69 peyote was such a

cool relaxed, and legal trip. What fun it was just moving from one friends house to the next. Music, matrimonial hammocks with six of us in it, “dirty martins comeback place”, so so loving and so so nice.

Its a time that I’ll never find again.

Peace

pms

Wonderful story, but a couple of nitpicks:

1. You forgot Bubble Puppy! I think they were from Houston but played nearly every week in Austin the summer of 66, usually at the Jade Room, on San Jacinto, I think(it’s a little hazy!), and were a very popular acid (or maybe ‘shroom!) rock band.

2. The I.L. Club on E. 11th Street – the building is still there, next to L.D. Davis’ White Swan – was a long-established black beer joint long before psychedelia came upon the scene, and endured as such long after. (I wouldn’t be surprised to walk in there today and find it unchanged.)

The Littlefields and their regulars were amused by the hippies, and they provided a venue for many acts, including Shiva’s and the rockabilly blues of Hub City Movers (Ike Ritter, Ed Vizard, and, I think, Angela Strehli’s brother, is it Al?). Fashionably-dressed black couples out on the town would stop by the I.L. to marvel at the hippy dancing, to them the most uncoordinated hopping around imaginable. Best were the nights when blues brought everybody together, and black couples and white couples alternated dancing on the small floor, the better to admire and/or be amused by other folkses’ strange ways.

But the first regularly-booked “underground rock club” in Austin was surely the New Orleans Club on Red River, and the 13th Floor Elevators were surely the first underground band to play there, in 1966. Woody Ashwood, who will be remembered by some of our Ghetto friends, used to run weed out of Mexico (so legend says) in his exterminator’s truck. He got a job bartending at the New Orleans, a flat-out frat club, and hooked the Elevators up with a gig, nearly losing his own job over it, until the manager figured out that the freaks were starving for a place to dance, would turn out in force every week, and could down as much cerveza as the frat crowd. Roky, et al, were the summer phenom; and who knew if there would ever be another summer anyway?

East Austin in general was very open and welcoming to the freak bands when other clubs stayed moronically stuck in the musical past. The first Vulcan Gas Co. lightshow wasn’t at the Congress Ave. club, but at Dorris Miller Auditorium in Rosewood Park, at a Shiva’s/Conqueroo/Bubble Puppy concert weeks before the Vulcan opened its doors.

Another place that deserves mention in the history of Austin psychedelic music is the Methodist Student Center, formerly located on Guadalupe St. The Meth early on had a beat-style coffee house, the Ichthus, where poetry was read and folk guitarists tried to raise money for their pot busts. There was also a large open auditorium with a stage, where folding chairs could be set up, or tables, or whatever was needed. Political meetings were held there. Plays were performed. People got married. Guided gently by Rev. Bob Briehan, the Meth was a popular, trusted gathering place, with the advantage of having a wise man on premise should one be needed. It is there that I remember first dancing to Shiva’s Head Band, and being totally happy and free.

No one who was around in those days could possibly think that the Elevators, for all that they were and all that Roky has become in the years since, were the only thing happening musically. In 1965 and 1966, somehow, the idea of making music and the ability to make music seemed to spread exponentially, so that people who’d never thought of themselves as musicians, or of music-making as accessible to the musically untrained, came to feel that “everything we do is music”, and an enormous amount of creativity was unleashed, and is still spreading ripples around the world.