Jay Jurie reports from the front lines of the labor movement.

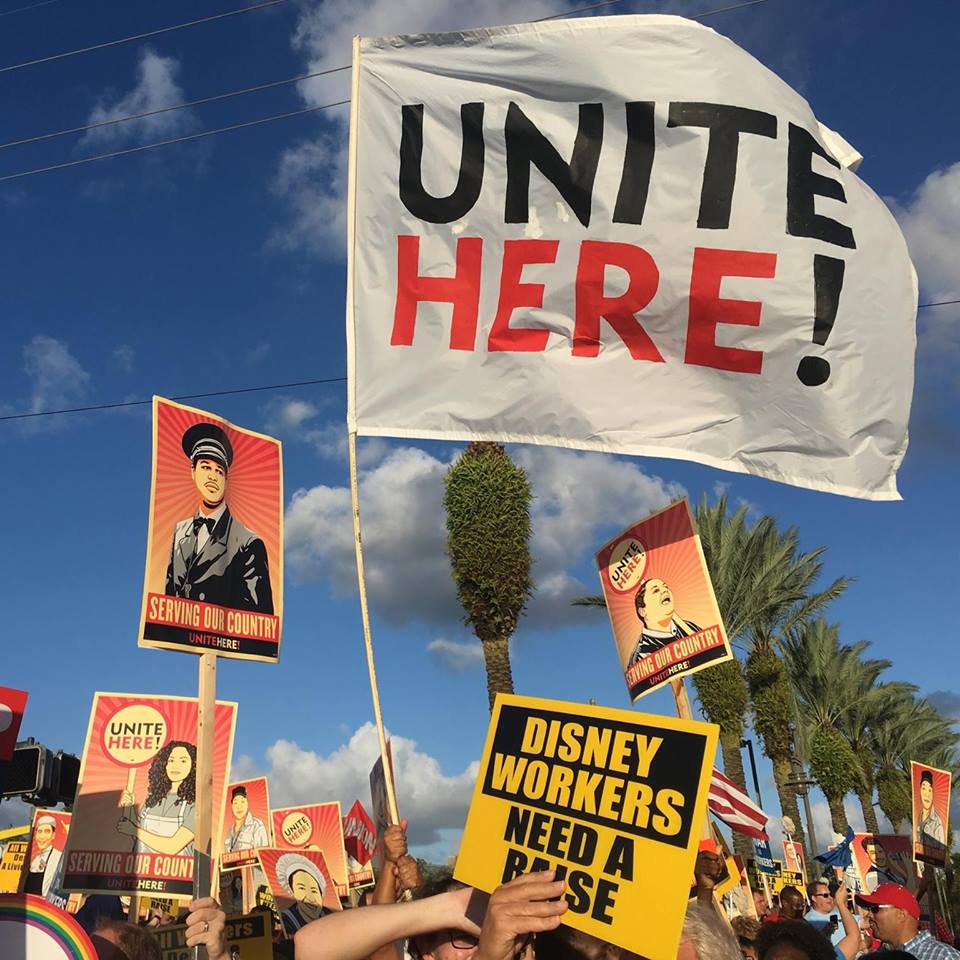

Photo from Unite Here! Central Florida.

ORLANDO, Florida — While representing over a third of workers in the middle of the 20th Century, unions today represent only a little over 10 percent of the total workforce. According to numerous sources, reasons for this decline include the shift from manufacturing and heavy industry to a high technology knowledge industry and an expanded service sector. Workplaces have become more dispersed and decentralized and employers have become increasingly centralized and reliant on cheap labor.

Growth of the public sector undercut unions by providing job security and relatively good benefits while simultaneously restricting union activity. Anti-union legislation such as the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, accompanied by state “right to work” laws, further weakened organized labor. A variety of comparatively less recognized factors have contributed to the decline of unions.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, union locals were often composed of immigrants who shared the same culture and language. This contributed both to labor solidarity and a sense of community. Often there was nativist hostility from sectors of the workforce who were not foreign-born. These trends combined with ongoing hostility to organized labor from employers and pro-business interests. Community declined as groups assimilated and were inculcated with individualist values that emphasized consumerism.

Portions of the labor movement that survived became victims of their own success.

Those portions of the labor movement that survived became victims of their own success. They became comfortable and complacent, generating bureaucracies that placed greater emphasis on maintaining their own positions rather than attention to issues affecting the rank and file — much less the trials and tribulations of the unorganized. A “business union” approach that focused on bargaining and higher pay was adopted. Competition rather than cooperation with “rival” unions became commonplace.

In recent years there has been evidence this orientation has been changing. Recognition has increased that if the labor movement is to survive, the slide into oblivion must be reversed. One example of this shift is a recent campaign launched by a consortium of unions that represent employees at Disney World near Orlando, Florida.

The entertainment industry, tourism, retail, and large-scale lodging enterprise have flourished in Florida’s right to work and historically low-wage economy. Much of the workforce is employed at or near minimum wage levels. Workers struggle with food, transportation, child care, and most particularly, housing costs.

While wages remain depressed,

rents have skyrocketed.

While wages remain depressed, rents have skyrocketed and affordable housing has become increasingly scarce. The Florida Project, a recently released and widely-acclaimed movie, views these conditions through the eyes of a young girl growing up in one of the numerous low-rent and run-down motels adjacent to the theme parks. Central Florida is not alone in producing landscapes like those found in the Third World: shimmering corporate monoliths based on poverty and flanked by slums.

In Central Florida, organized labor came to see that the Disney Corporation was the lynchpin. Since it set the prevailing wage rate and the rest of the region followed suit, and since it had the highest profile in the local entertainment and service industry, a decision was reached to launch a $15 per hour minimum wage campaign targeting Walt Disney World.

Photo from Unite Here! Central Florida.

Recently a consortium of Disney-related unions organized by Unite Here! gathered outside one of the main entrances of the Magic Kingdom to kick off a campaign demanding a pay raise. Currently, many of those employed as drivers, servers, housekeepers, and other service trades only earn around $10 an hour.

About 2,000 turned out for this demonstration, which straddled all four corners of one of the busiest intersections in the Orlando area. Participants reflected the demographic diversity characteristic of Central Florida’s working population: young, old, male, female, black, white, and Hispanic were all well represented, Spanish and Creole were spoken alongside English.

Participants were motivated and energized.

Although wages are low, spirits at the event were high. Participants were motivated and energized. There were a variety of t-shirts, buttons, signs, banners, floats, chanting, marching, drums, whistle-blowing, and one man playing a rhythmic beat on a trumpet.

An hour into the event, crowds of people starting marching from corner to corner, slowing traffic until all made it across. This went on for 15 or 20 minutes until a dozen people carried two large banners into the middle of the intersection and sat down. Traffic immediately ground to a halt.

Amazingly, there were no police in sight. The group sat with the banners for about 10 minutes until the Orange County Sheriff’s Department showed up in force, arriving in multiple vehicles with lights flashing and sirens blaring. Immediately those in the middle of the intersection got up and melted into the crowd.

Then another contingent launched a sortie onto Disney property that deputies scrambled to head off. Others resumed crossing the street from corner to corner, but now with deputies directing traffic. This went on for about half an hour until one deputy used a patrol car speaker to declare the demonstration an “unlawful assembly.” Participants then slowly dispersed, so about half an hour before Unite Here’s previously announced end time, the event was over.

No doubt some will criticize the unions

for blocking traffic.

No doubt some will criticize the unions for blocking traffic, many doubtless will criticize the labor movement no matter what it does. Those who make such arguments need to get a grip; all those who have little or no choice but to work for Corporate America’s substandard wages suffer far greater inconvenience day in and day out. This was not Chris Christie misusing official authority to shut down a bridge for selfish political purposes.

All in all, the event was exhilarating. Highly visible nonviolent disruption was used to drive home its message. Unite Here! showed how it’s done.

It is to be hoped this worthwhile demonstration was only the opening salvo of a successful campaign to win the standard of living these workers deserve and will serve as a model for others. Leadership capably exhibited an openness to new tactics as well as an understanding that from diversity labor can and must forge an inclusive sense of community. While the explicit objective of this campaign is a wage increase, that sense of community and renewed engagement with the larger social setting is critical both to winning this fight and to rebuilding organized labor.

[Jay D. Jurie, Ph.D., an associate professor of public administration and urban and regional planning at the University of Central Florida, is a member of the Central Labor Council of the Central Florida AFL-CIO. Jay lives in Sanford, Florida. Read more articles by Jay D. Jurie on The Rag Blog.]

- Read more articles by Jay Jurie on The Rag Blog.