Heyday is brave to have published this book, which blows the lid off the BPP.

Mention the two words “Black Panther” to anyone under the age of 40, and they’re likely to think, right off the bat, of the 2018 action, adventure film Black Panther. They’re not likely to think of the Black Panthers of the Sixties, who were superheroes to a generation or two of Americans, both black and white, and who were as deeply flawed as any tragic heroes in any film.

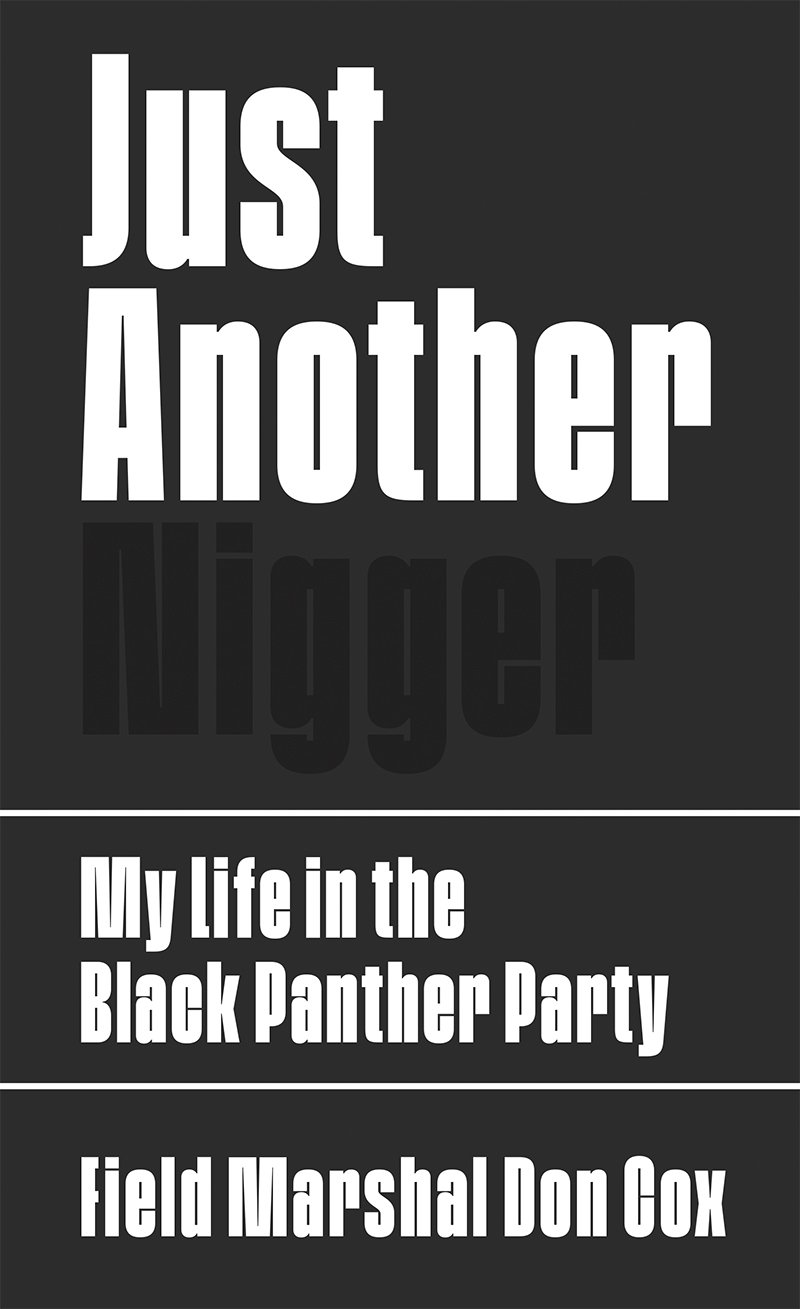

Don Cox’s Just Another Nigger: My Life in the Black Panther Party ($28), which has just been published by Heyday in Berkeley, will not replace Ryan Coogler’s movie, Black Panther in the pantheon of popular American culture, but it will dispel many if not all of the myths that have surrounded the Black Panther Party (BPP) and its two founders, Huey Newton, who was killed in Oakland in a drug deal gone awry in 1989, and Bobby Seale, who is still alive and a shadow of his former self, though he performs very funny stand-up comedy.

Cox served as the Black Panther Party’s ‘Field Marshal.’

Cox, who first broke into radical political activity in San Francisco, served as the BPP’s “Field Marshal,” a title he enjoyed for a time because he admired the British military strategist, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery.

Heyday and its executive director, Steve Wasserman, are brave to have published this book, which blows the lid off the BPP. Cox was a brave man to have written this candid account of his life in and around the BPP and that includes incisive portraits of many of its leaders, including Newton, Seale, Eldridge Cleaver, Fred Hampton, who was murdered by the police in Chicago while he was sleep, and David Hilliard who emerges as a villain in Just Another Nigger.

But there are many other villains in the book. “If you get an African American lumpenproletariat to love Stalin, you either have a true revolutionary or a cold-blooded killing machine,” Cox explains. He adds that Stalin’s The Foundations of Leninism was a bible in the BPP. More often than not, BPP members became “cold-blooded killing machines,” or its victims. Newton and Cleaver, he insists were “newer versions” of Hitler, Stalin, Hoover, and Nixon.

He describes his own ‘love affair with guns.’

Cox doesn’t exonerate himself or his own deeds and misdeeds. Rather, he describes his own “love affair with guns,” his actions as a “sniper” in San Francisco, where he was a civil rights activist. In the early 1960s, he picketed Macy’s to end its policy of racial discrimination against employees. Later, as his rage boiled over, he stockpiled guns, took aim at, shot, and wounded at least one San Francisco police officer, and wisely never claimed credit for it.

He also took part, he says, in a string of robberies, burglaries, and raids on U.S. post offices. When he asks himself why he acted as he did, he turns to his own background and lays much of the blame on his “rural religious upbringing.” Born in 1936, and raised in Missouri, he came west with his parents, and attended college in San Francisco. He could read and write and think critically, much of the time, and held a 9 to 5 job. As a commercial photographer, he had a sense of form and shape and beauty, and while he says that he was “a respectable nigger by day and a guerrilla by night,” he doesn’t seem to have become a full-time guerrilla.

What saved him was his grandmother. As he explained to a black nationalist, “if for no other reason than my grandmother being white, I would not, could not ever hate all white people.”

Cox wrote his book in the 1980s and tried unsuccessfully to find a publisher.

Cox wrote his book in the 1980s and tried unsuccessfully to find a publisher at that time. Before he died in 2011, at the age of 74, he gave the manuscript to his daughter, Kimberly Cox Marshall, and made her promise to find a home for it. “When things started to go bad in the party, there were two kidnapping attempts on me, and one night a woman came to our house to kill my mother, brother, and me,” she writes in a foreward in which she calls Cox, “Daddy,” and who had long since abandoned his family, remarried and had a relationship with a woman Kimberly calls “a mistress.”

With the publication of Cox’s book, no intelligent person will be able to say with impunity that he or she was never aware of the true, behind-the-scenes history of the organization that was born in 1966, sowed the seeds of its own violent destruction, and that all but disappeared by 1972, though some individuals tried to carry on for decades.

I spent a week with “DC,” as Don Cox was known, in Algiers in 1970, along with Eldridge Cleaver and Timothy Leary, all of them in exile from the U.S. and wanted by the FBI and the CIA, as FOIA documents make clear. When DC died, I wrote and published an obituary about him in which I called him “The Wistful Panther.” DC had explained, while we were both in Algiers, that in “Babylon” — the Panther name for the U.S.A. — he was unable to appreciate the beauty of the moon at night. In Algiers, he had the peace of mind to look into the night sky and gaze with a kind of reverence at the light from our moon.

The wistful Panther was also a Panther haunted by the history of bloodshed.

He also took me to the edge of the city, pointed down to the Mediterranean and invited me to notice the color of the waters, dyed red, he insisted, by Algerians slain by French soldiers, their bodies dumped into the sea. The wistful Panther was also a Panther haunted by the history of bloodshed in the U.S. and around the world.

In the 1970s, I knew Huey Newton, and I worked on a committee to defend a group of New York Panthers who were arrested in 1969 and charged with a variety of crimes, including conspiracy to blow up the Statute of Liberty. After Newton’s death, Dave Hilliard, once the chief of staff of the BPP, invited me to write Huey’s biography.

The catch was that Hilliard would have final say about what would appear in print. I declined the offer and haven’t ever been sorry that I did so. I also met with and interviewed Cleaver in the Alameda County Jail in 1976 after he surrendered to and cooperated with the authorities. By then, he called himself a Republican and a born-again Christian. He seemed to have turned himself inside out and upside down.

Some readers will disapprove of the use

of the ‘N’ word.

Doubtless some readers will disapprove of the use of the “N” word in the title of Don Cox’s political autobiography, though the quotation from W.E. B. Du Bois at the front of the book, might persuade them to relinquish their opposition, whether they’re black nationalists or white liberals. Du Bois, who helped start the NAACP — and who wrote in The Souls of Black Folk that the “The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line” — also explained in a speech broadcast on Radio Peking in 1959 that, “In my own country for nearly a century I have been nothing but a nigger.”

Comedian, civil rights activist and life-long American gadfly Dick Gregory called his autobiography Nigger. H. Rap Brown called his book, Die, Nigger Die! Don Cox uses the word “nigger” all the way through his book, though he also uses the word “colored” and “blacks.” Why he uses the “n” word so often isn’t clear. He writes about “niggers with guns,” “good niggers,” and “niggers from all over the Bay Area.” To his own son, Donnie, he wrote “Hey Nigger, why don’t you write.”

Too bad DC didn’t live long enough to see the publication of a book that Heyday calls “incendiary.” He died in a mountain village in France far from the San Francisco Bay Area, where Just Another Nigger is bound to stir up memories, generate debate, and provoke discussion about Black Power, the Black Panthers, “blind faith,” and the dream of a world DC shared with friends, comrades and lovers of a world with “food, clothing and shelter for everyone.”

This article was first published at Beyond Chron: The Voice of the Rest and was cross-posted to The Rag Blog.

[Jonah Raskin, a frequent contributor to The Rag Blog, is the author of For the Hell of It: The Life and Times of Abbie Hoffman and American Scream: Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” and the Making of the Beat Generation.]

- Read articles by Jonah Raskin on The Rag Blog and listen to Thorne Dreyer’s Rag Radio interviews with Jonah.

I gotta read this. I interviewed DC for The Rag and I was impressed by him long after I was convinced we were going to regret lionizing most of those guys. DC’s vibe was different. I did not think he seemed like a man out for the main chance.

Thanks for posting this.