Some may be surprised that there was an Underground Railroad network in Texas.

We are all familiar with the tales of the Underground Railroad, how enslaved people in the South risked life and limb to escape to the Northern States before and during the Civil War.

Some of us may be surprised to learn that there was an Underground Railroad network in Texas. Maria Hammack, whose research on this subject is coming to light in a doctoral thesis at the University of Texas in Austin, estimates that before the Civil War between 5,000 to 10,000 slaves escaped to Mexico to obtain their freedom.[i]

And I am fairly sure that most of us would be astounded to learn that there may have been a way station for this Underground Railroad in Blanco County.

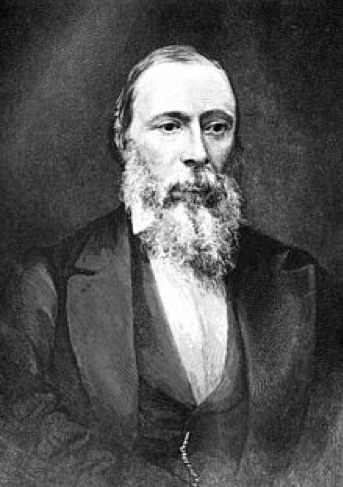

The intriguing evidence for this way station comes from the early letters of Jean Charles Houzeau, a Belgian astronomer who lived in Texas in the early years of the Civil War and who was forced to flee Texas because of his abolitionist activities.

In a letter dated September 20, 1861, to his colleague Van Bemmel in Belgium, printed in the Revue Trimestrielle, and later collected and reprinted as La Terreur Blanche Au Texas (The White Terror in Texas), Houzeau writes of his experience near Smithville in which a group of African American slaves are prompted to escape from their local overlords. Their plan for escape from Smithville is aided by a local Methodist minister and by Houzeau.

Houzeau relates:

I had promised to assist the runaway slaves, and in the hope of meeting them, I cut through the most deserted and wildest parts of the countryside. I arrived one evening at the edge of a small rugged river, which flows between limestone rocks, resembling ruined castles and dismantled citadels. This white belt of rock walls has earned the stream the name of Rio Blanco. I was hoping to cross the plateau faster by ascending to the source of the river. Oak forests, of a dark color, which contrasted with the bright edge of the water, seemed to continue at any distance. It was therefore not without astonishment, nor without some kind of pleasure that I came across, at the head of water of the Blanco River, an isolated farm, the remotest oasis of the county. [ii]

Houzeau was later joined at this “isolated farm” in “the remotest oasis of the county” by the same escaping group of slaves from Smithville, who seem to have known where to rendezvous. This indicates that it may have been a prearranged stop on the Texas Underground Railroad, or perhaps it was an incidental stop: Houzeau relates that the unnamed settler at the farm is not an abolitionist, but offers food and lodging for his unannounced guests.

The escapees were on their way by the next morning and Houzeau speculated that they “must be free… anywhere in the territory of Mexico.”[iii]

In 1861 the headwaters of the Blanco River were within the boundaries of Blanco County. In 1862 Kendall County was established, whereupon the headwaters of the Rio Blanco would be in Kendall County.

Why would a group of escaping slaves have traveled west from Smithville to escape to Mexico? For a variety of reasons, not the least being that the Eagle Pass/Piedras Negras path to Mexico would have been the shortest route. It would have also been in a less populated area, free from the pro-slavery plantation areas of eastern Texas. And it would have been a friendlier route (the possibility of encountering hostile Native Americans notwithstanding): the German population of the Hill Country was adamantly against slavery and Blanco County voted overwhelmingly against secession in February 1861. The Freethinker German settlements of Sisterdale and Comfort, both militantly political against slavery, would have been along the route.

Another tantalizing clue for the existence of a way station on the Texas Underground Railroad in the Hill Country is given in the autobiography of Dr. Adolph Douai. Douai was an ardent abolitionist and a refugee from the 1848 revolution in Germany. He resided for a period of time in Sisterdale, 10 miles as the crow flies from the headwaters of the Blanco River. Douai remarked: “The Negroes often escaped to us and then easily fled to Mexico.”[iv]

The Eagle Pass/Piedras Negras crossing into Mexico appears to have been a long-standing route for crossing into Mexico. It was used by the Kickapoo tribe to enter Mexico in 1850, as well as by the Seminoles in the same year (it should also be remembered that there were many escaped slaves assimilated within the Seminole tribe). It had been established as a budding crossing point for escaping African American slaves as early as 1836,[v] and the travelogue of early Texas explorer Frederick Law Olmstead talks of a colony of freed slaves there in 1857.[vi]

In 1855 Blanco County settler and Texas Ranger James Callaghan purportedly undertook a punitive expedition against marauding Lipan Apaches to Piedras Negras and Eagle Pass, but there is ample documentation to suggest that Callaghan was on a mission to recover runaway slaves. Failing to recover any escapees and encountering resistance from the Mexican population, Callaghan burned Piedras Negras to the ground.[vii]

The land of the headwaters of the Blanco River were later acquired by Amos Valentine Gates in 1872. Gates was elected Chief Justice (County Judge) of Blanco County on September 21, 1861, the day after Houzeau wrote his letter to Von Bemmel. Strange coincidence.

[Steve Rossignol is a member of the Blanco County Historical Commission.]

[i]“The Little-Known Underground Railroad That Ran South to Mexico,” Becky Little, History.com, August 28, 2019, https://www.history.com/news/underground-railroad-mexico-escaped-slaves, accessed January 30, 2020.

[ii] Jean Charles Houzeau, La Terreur Blanche et Mon Evasion, V. Parent et Fils, Brussels, 1862, p. 23 ; translated from the French by Wikisource as The White Terror in Texas and My Escape, https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Translation:The_White_Terror_in_Texas, accessed January 30, 2020.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Adolph Douai, Autobiography, translated by Richard H. Douai Boerker, unpublished manuscript, 1957. Douai Papers, Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin. Douai would be forced by angry secessionists to flee Texas in 1855. He settled in Boston and became one of the leading figures of the Socialist Labor Party.

[v] Ronnie C. Tyler, “Fugitive Slaves in Mexico”, The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 57, #1, January 1972, p.2.

[vi] Frederick Law Olmstead, A Journey Through Texas, Austin, University of Texas Press, 1978,

[vii] Ronnie C. Tyler, “The Callahan Expedition of 1855: Indians or Negroes?” Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. 70, #2, April 1967.

Jean Charles Houzeau in 1891. From Popular Science Monthly.

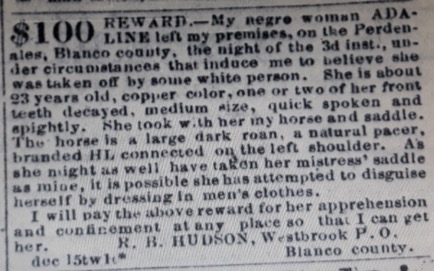

From the Tri-Weekly Telegraph (Houston), December 15, 1862.