The author replies to Raskin’s ‘Rag Blog’ review of ‘All-American Rebels.’

[The following is a response to Jonah Raskin’s August 18, 2020 Rag Blog review of Bob Cottrell’s latest book, All-American Rebels: The American Left from the Wobblies to Today. Read Raskin’s review here.]

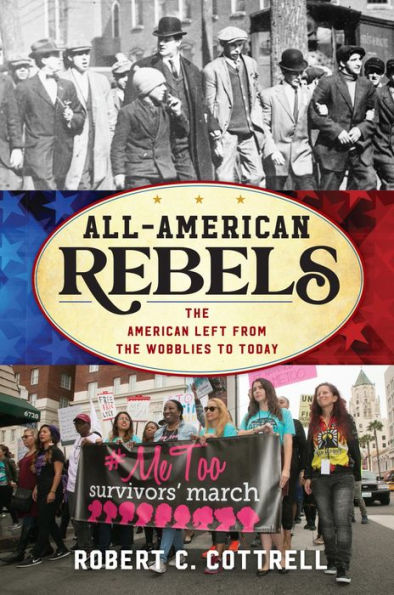

I admire Professor Jonah Raskin’s work, especially his studies of Abbie Hoffman and Allen Ginsberg. I also appreciate the seriousness with which he tackles my new book, All-American Rebels: The American Left from the Wobblies to Today. I appreciate the blurb he offered for it: “Essential reading for those who participated in the struggles for equality and justice, and for those who are eager to learn about the history that has often been whitewashed from the official story.” The longer blurb he offered was still more complimentary, but my publisher opted to condense it.

Perhaps Professor Raskin has had a change a heart. While writing, “There’s hardly an important rebel who isn’t mentioned in passing in the pages of Cottrell’s book,” he points to a sin of commission on my part. That involves an inexplicable failure, notwithstanding numerous reads on my part, to list Huey Newton (whom I taught about for forty years), rather than Eldridge Cleaver, as a Black Panther co-founder. Professor Raskin also notes a sin of omission, the leaving out of Allen Young of the Gay Liberation Front. Unfortunately, these are probably not the only acts of commission and omission in a work as synthetic as this one, operating under the word count limitation I was handed.

Professor Raskin quibbles about my charge that Eric Hobsbawn (one of my favorite writers) “framed the communist world view poetically, if far too romantically” in discussing the CPUSA’s response to the Nazi-Soviet Pact, although the great Marxist historian’s own relationship with the party was lengthy and complicated. Implicitly criticizing my reference to the “crushing” nature of the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy, Professor Raskin writes that I “don’t allow for rebounds and the resilience of civil rights activists who are still in the thick of the fight.” This despite the fact that the last several chapters refer to considerable civil rights engagement, including as exemplified by the prisoner rights movement, the national welfare rights movement, People United to Save Humanity (later People United to Save Humanity, Operation PUSH), MOVE, the Jesse Jackson-spawned Rainbow Coalition, and #BlackLivesMatter.

Professor Raskin questions my statement that the counterculture possessed ‘fatal flaws.’

Insisting that I’m “often too quick to bury movements and causes and write their epitaphs,” Professor Raskin questions, for instance, my statement that the counterculture, of which I’ve produced the lengthy exploration he notes, possessed “fatal flaws.” Among the flaws I underscore are “sexism, even misogyny, degrees of racism, and a too ready attraction for the very material objects it supposedly reviled. And drugs both connected first the beats and then the much larger group of hippies, but also left in their wake ruined lives and ravaged minds,” with “the young, with not wholly formed psyches . . . especially prone to becoming casualties of the resort to illicit pharmacology.”

But before I offer that analysis, I write, “At its purest, the counterculture, as exemplified by beats and hippies, fit within the pantheon of American radicalism. Commercialism ensnared the counterculture of the 1960s and later, and yet, for a time at least, it possessed radical, arguably even revolutionary potential, as the Yippies and members of the Establishment recognized. Before failing prey to it, the counterculture challenged that very commercialism, along with capitalism itself, through communes, collectives, cooperatives, and groups like the San Francisco Diggers, who gave away food and clothing, and symbolized the counterculture at its essence.

Publicized by underground newspapers that threaded the counterculture, free concerts and hip stores demonstrated the possibility of an alternative mode of operating. The underground press, initially including the Los Angeles Free Press, Fifth Estate (Detroit), the East Village Other, the Berkeley Barb, the San Francisco Oracle, and The Rag (Austin), sought to evangelize for both the counterculture and the Movement. Eventually, hundreds of underground publications cropped up, some lasting for only a few issues but others, like The Rag, serving as both a fulcrum for radical ideas and something of a community, notwithstanding often hostile and sometimes dangerous, even deadly, environments. Founded by Raymond Mungo and Marshall Bloom, Liberation News Service strove to weave together anti-establishment papers and offer “hard information” to Movement activists.

Furthermore, I extol the counterculture’s “emancipatory” quality and its spurring of “incredible visible artistry, in addition to . . . musical brilliance.” Alas, I was able to devote about a page to the topic in All-American Rebels, one that my book on the counterculture covers over 360 pages of text.

Robert Cottrell on Rag Radio,

May 24, 2019.

Professor Raskin devotes most of his criticism to my analysis of the CPUSA and Weatherman. I am, admittedly, critical of each, although I believe in more nuanced fashion, particularly the CP, than he credits. I do believe that both made fatal errors, which, in the process, proved damaging to the Old Left, in the case of the CP, and the New Left, in that of Weatherman. But I hardly fail to note the idealism of John Reed as Professor Raskin suggests, or the CP’s support for labor unions, the unemployed, the Scottsboro Boys, the Spanish Republic, and the rich outpouring I refer to as Radical Culture, which sprang forth during the 1930s and somewhat beyond. A financial pipeline to first communist Russia and then the Soviet Union did exist, and it did involve some distinguished figures. The reactionary publisher, Henry Luce, did foolishly refer to Stalin as “Uncle Joe.”

The party did, in effect, genuflect for too long to Holy Mother Russia. That doesn’t negate the good work individual party members did but refusing to acknowledge its misdeeds hurt the left at the time and hardly helps to further the historical record of both the CP and the American left. I am probably harsher toward Weatherman, possibly because their splintering of SDS, much aided by Progressive Labor, tore that group asunder and left an organizational vacuum that the New Left never filled. That’s the same New Left I considered myself intimately involved with, as I was with the counterculture.

As Professor Raskin notes, I have spent much of my professional career studying and writing about radicalism in the US during the twentieth century and beyond. I do so as one who has been inextricably attached to it since I became radicalized during the spring and summer before I began my undergraduate studies during the fall of 1968. The assassinations, Columbia, Paris, the coup in Czechoslovakia, and the police riots in Chicago helped to further my own process of radicalization, one I haven’t deviated from since.

At the same time, I have an aversion to dogmatism, sectarianism, and vanguardism. Moreover, I believe that those characteristics have badly tainted the American left. I am, admittedly, intolerant of intolerance. That may be a major flaw on my part, but I don’t apologize for such a sensibility. At the same time, critical perspectives don’t equate to demonizing and scapegoating.

[ Robert C. Cottrell is professor of history and American Studies at Cal State Chico. He has written biographies of the radical journalist I. F. Stone, ACLU icon Roger Nash Baldwin, and Negro League founder Rube Foster. He has authored a book on World War II-era conscientious objectors and a dual biography of Hank Greenberg and Jackie Robinson. His most recent books are All-American Rebels: The American Left from the Wobblies to Today; Sex, Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll: The Rise of America’s 1960s Counterculture; and 1968: The Rise and Fall of the New American Revolution.]

- Listen to Thorne Dreyer’s May 24, 2019 Rag Radio interview with Robert C. Cottrell.

Thanks. Both a lively review and response. A thoughtful exchange, overall an informative discussion.