The End of Newspapers? Or is there a Journalism School Model?

By Juan Cole / March 1, 2009

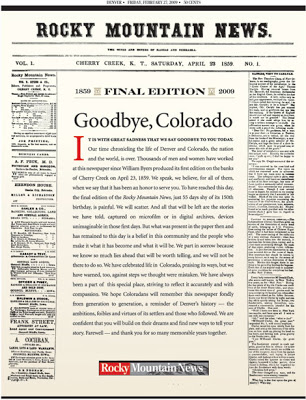

You wonder if the last front page article in the last newspaper will be about the demise of the newspaper?

I especially regret the possibility that the San Francisco Chronicle might close, or become part of a single-owner print media monopoly in the Bay area. The Chronicle has been one of the papers I have regularly checked in on ever since newspapers started being available on the web. I’d be sad if it were gone.

I attended a conference of editors of major foreign policy magazines in London a couple of years ago, and we had a presentation from a major UK newspaper. The editor said that he couldn’t be sure of still being in business in five years. Their advertising in the print edition kept falling off, subscriptions and circulation were in a tailspin, and the internet was a monetary black hole. They had tried charging for internet access, and few readers ponied up. They had tried putting it up for free but trying to attract advertising. But the advertisers were not sure of the value of “hits” and “page views” and wouldn’t advertise much online nor pay much for an ad (tell me about it). So basically the newspaper was entering a world in which there was no business model.

The presentation was prophetic.

I worked for a newspaper in Beirut in my 20s. I have always enjoyed newspapers, and it has been one of the benefits of becoming a prominent blogger that I got to have a lot to do with journalists, with whom I usually have a lot in common. And, I’ve benefited enormously from the active news-gathering of journalists, often at the risk of their very lives.

Journalism is two parts: news-gathering and commentary. I’m on the commentary side for the most part, though very occasionally I do some news-gathering. Since the nineteenth century, academics have often been commenters, so the only thing new is that because of the rise of the internet and blogging, I did not have to begin by convincing an editor to publish me. Since editors are hard to convince, and many in journalism appear to have been traumatized somewhere along the way by an incomprehensible professor, it was better that way.

It does seem odd that so few of the prominent bloggers of the early to mid zeroes ended up with long-term stable positions in traditional media. After all, they have proved that they could attract hundreds of thousands or even millions of page views. It was as though print media editors and owners just couldn’t see the new medium nor its flora and fauna, until it was too late. I can remember hearing back that op-ed editors were nervous about commissioning pieces from bloggers, because the bloggers wrote so much they were over-exposed. They did not realize that a city newspaper was then a whole different market and readership than the blogosphere (the two overlap more now).

And now the newspaper as a form of print publication may be on its last legs. And whereas I have a paying day job, news-gathering journalists are in danger of losing theirs, and they are a little unlikely to go on doing difficult and sometimes dangerous news-gathering on a pro bono basis.

Some have suggested that we go to an endowment model for newspapers. I’m all for it. Others have warned that it would make the newspapers beholden to rich donors. Surely you jest. The old joke was that anyone can own a newspaper, all you need is a million dollars (it is a really old joke; you’d need a lot more than that.) One of the problems with newspapers is in fact that usually they are owned by the wealthy, and often the wealthy stuck their fingers into the machinery of the newspaper.

As long as internet neutrality, what I call internet liberty, isn’t crushed, the demise of the traditional newspaper holds out the possibility of a press that more closely reflects the interests of the ordinary people, instead of the urban business classes.

So the endowment model is in my view actually much less likely to make the reporters beholden to special interests. Once the money is in the endowment, the donor’s leverage is much reduced. Of course, if you were actively trying to increase the endowment, you might be tempted not to make waves . . . But presumably that would not be the normal state of affairs for all endowed journalists. It should be a 501 c 4 endowment rather than c3, i.e., the kind that allows partisan political activity.

The main problem with the endowment model is that an endowment has to be just enormous to generate enough money to accomplish anything. A conservative approach to an endowment would dictate that only 5 percent of the annual profit generated by the principle should be available for spending. To pay a senior journalist $100,000 a year, you’d need $2 million in the bank, and with fringe benefits it would be $2.5 mn. A staff of 40 journalists and editors would require an endowment of $100 mn.

Have you ever tried to get anyone to just give you $100 million? And that was when anyone had it to give.

It does occur to me that there is one institution that routinely raises that sort of money, which is the university. I wonder if the journalism school might not be the matrix of the web-based newspaper of the future. (How to mix between public and private, and 501 c 3 and 501 c 4 type endowments I don’t pretend to know). But if it were possible, and if the school had the journalists do some teaching, so as to be able to attract tuition money, you might be able to generate proper salaries and leave enough time for newsgathering and writing. How to handle foreign correspondents isn’t clear, but a city beat wouldn’t be so hard. And after all, you could have the Paris and Berlin city beat correspondents translated to get the international news. You might also have to take subscriptions from readers who want a month-long series from e.g. Baghdad, the way the 18th century travel writers did (readers who wanted a true-life adventure book preordered it and so allowed it to come into being.) That would be a sort of MoveOn.org model for some journalism.

And if the journalists taught some courses, those courses wouldn’t have to just be on journalism. They’d after all be fine teachers of writing, and some have disciplinary specialties. But an institution that taught clear, hard-hitting writing would be golden in itself. Despite the handwringing about liberal arts education, there are still lots of companies that want employees who can write clearly and concisely and powerfully. They’ll eventually be hiring again. (It is a little ironic that the newspapers, which are running stories about how iffy a liberal arts education is in hard times, are the ones in trouble. Whereas my university, which teaches the liberal arts, is so far doing just fine, as are most of its graduates.)

Now journalists might accuse me of trying to rope them into my crazy kind of life. But I really am just thinking out loud about how to save the profession. Lots of new models will likely emerge, since there certainly is a market for news. The academic Journalism School/ Newspaper may be one of them.

Of course, another possibility is for newspapers and news magazines to find ways of getting customers to pay for subscriptions, even on the web. Salon.com, for which I write a regular column, has as far as I know been running in the black. It began as a co-op, and does remarkably independent journalism. For those of you who care about this issue, and good journalism, I urge you to subscribe if you can afford it nowadays. (You can tell if you can afford it if you still ever get Starbucks capuccino-style drinks).

Source / Informed Comment

Newspapers selling propaganda to illiterates and spurning their proper role as the “fourth estate” are not worthy of survival. Case in point is the Casper, WY, Star-Tribune, whose editor prints a conservative rant of a reader filled with errors about the US compared to Canadian and UK health care system, and ignores the attempted correction of another reader who cites a URL to a scholarly study to correct the record. The world will be a better place when papers like the Casper, WY, Star-Tribune go out of business, IMHO.