‘In the wishful-thinking corner of my mind, pushing the limits and fostering social change are inextricably connected, but I don’t have any delusions that I’ve inspired an epidemic of epiphanies.’ — Paul Krassner.

By David Kupfer

[David Kupfer’s interview with Paul Krassner appears in Issue 398, February, 2009, of The Sun magazine.]

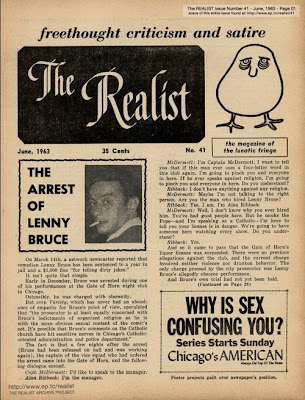

Paul Krassner has been spreading his witty, sometimes snide, and often political brand of humor since the late 1950s. His publication the Realist was the underground journal of the counterculture during the sixties and seventies, breaking political stories and covering topics that were taboo for the mainstream press. Krassner became known for interweaving current events, social criticism, and satire in a manner not previously seen in print.

Born and raised in New York City, Krassner was a violin prodigy, and in 1939, at the age of six, he became the youngest person ever to perform at Carnegie Hall. In the 1950s he worked as a writer for comedian Steve Allen and for Mad magazine, and he became friends with stand-up comic Lenny Bruce. Krassner edited Bruce’s autobiography, How to Talk Dirty and Influence People, and at Bruce’s encouragement began performing stand-up comedy himself at the Village Gate nightclub in New York City.

As editor of the Realist, Krassner approached journalism not as an objective observer but as a participant in many of the stories he covered. After he interviewed a doctor who performed illegal abortions, Krassner ran an underground abortion referral service. He wrote about the antiwar movement while he was an active member of it. And in addition to publishing articles on the psychedelic revolution, he took lsd with the revolution’s unofficial leader, Harvard psychologist Timothy Leary, and the spiritual teacher Ram Dass, a former associate of Leary’s at Harvard. Later Krassner joined novelist Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters, who traveled the country spreading the gospel of psychedelics.

In 1967 Krassner cofounded (with Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin) the Yippies, a countercultural political party that led theatrical demonstrations outside the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago. At the height of the Vietnam War, Krassner was on an fbi list of radicals to be rounded up in the event of a national emergency. His friends John Lennon and Yoko Ono financed a 1972 issue of the Realist that exposed the Watergate break-in before journalists Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein did so in the mainstream press. In 1978 publisher Larry Flynt hired Krassner to take over the pornographic men’s magazine Hustler. The job lasted only six months, during which time Krassner appeared as a centerfold in the magazine.

In 2004 Krassner received an American Civil Liberties Union Upton Sinclair Award for his dedication to freedom of expression, and at the fourteenth annual Cannabis Cup in Amsterdam, Krassner was inducted into the Counterculture Hall of Fame by the publication High Times. His articles have been published in Rolling Stone, Playboy, Penthouse, Mother Jones, the Nation, the New York Press, National Lampoon, the Village Voice, the Los Angeles Times, and Funny Times. The Realist printed its last issue in 2001, but Krassner is still active as a writer, contributing a monthly column to High Times and a bimonthly column to Adult Video News Online. He is a regular columnist for the Huffington Post website and has been actively involved in movements to end the Iraq War and to legalize marijuana. (“Cigarettes are legal, and smoking them causes the death of twelve hundred people a day,” he says. “Marijuana is illegal, and the worst side effect is maybe you’ll raid your neighbor’s refrigerator.”)

Krassner has released six comedy albums and authored numerous books, including his autobiography, Confessions of a Raving, Unconfined Nut: Misadventures in the Counter-Culture (Touchstone) — which he is currently updating and expanding for a possible new edition — and One Hand Jerking: Reports from an Investigative Satirist (Seven Stories Press). His most recent collection, Who’s to Say What’s Obscene? Politics, Culture, and Comedy in America Today, will be published by City Lights Books in July of this year.

Krassner lives in southern California’s Desert Hot Springs with his wife, Nancy Cain, whom he married on April Fool’s Day twenty years ago. When I arrived at their home, just prior to last year’s presidential election, he answered the door wearing jeans and a black t-shirt that said, “Stop Bitching — Start a Revolution.” He walks with a cane because of a beating he suffered at the hands of two San Francisco cops during the riot following the voluntary-manslaughter verdict in the trial of Dan White, who had assassinated Mayor George Moscone and City Supervisor Harvey Milk. Krassner’s dark, curly hair and youthful demeanor make him appear younger than seventy-six.

On the walls of Krassner’s home office hang a portrait of Albert Einstein with the maxim “Imagination is more important than knowledge,” a photo of the Great Pyramid of Giza (from when Krassner traveled to Egypt for the Grateful Dead concerts there in 1978), and a trickster icon from a healers-and-shamans expedition in Ecuador. Outside the window, in a part of the yard he calls “Birdland,” doves, finches, and starlings were bathing, and hummingbirds hovered by huge blossoms. We were serenaded by a mockingbird Krassner had nicknamed “Plagiarist.” True to form, halfway through our conversation, Krassner lit up a fat joint.

Kupfer: Who are your influences?

Krassner: I come out of a tradition of American humorists that includes Mark Twain, H.L. Mencken, and Will Rogers. My first modern influence was Lyle Stuart, who published the Independent, where I did my apprenticeship in journalism and wrote a column titled “Freedom of Wit.” Another of my mentors was Jean Shepherd, the radio humorist. In the middle of the night he’d talk about how you might explain an amusement park to a Venusian, or about a man who could taste an ice cube and tell you the make and model of the refrigerator it came from. Comedian Lenny Bruce was my role model as a stand-up performer, and novelist Joseph Heller was my biggest influence as a satirical writer. Heller explained to me how, in his book Catch-22, he used exaggeration so gradually that unreality became more credible than reality.

Kupfer: You have done stand-up comedy for nearly fifty years. How have your audiences changed?

Krassner: I think they’re more aware now of the contradictions in society: the phony piety, the hypocrisy. And I’ve evolved right along with them. Performing, for me, is a two-way street. English is my second language. Laughter is my first.

Kupfer: Do you aspire to foster social change with your satire, or do you just want to see how far you can push the limits?

Krassner: In the wishful-thinking corner of my mind, pushing the limits and fostering social change are inextricably connected, but I don’t have any delusions that I’ve inspired an epidemic of epiphanies. People don’t like to be lectured to, but if you can make them laugh, their defenses come down, and for the time being they’ve accepted whatever truth is embedded in your humor. When a large audience of people are all laughing together, no matter how disparate their backgrounds are, it’s a unifying moment. But who’s to say how long that moment of truth or unity lasts and whether it leads to any action? It’s one more positive input, but rarely a tipping point.

Kupfer: What pushed you into the role of provocateur?

Krassner: I couldn’t help but notice the difference between what I experienced in the streets and the way it was reported in the mainstream media, which acted as cheerleaders for the suppression of dissent.

Kupfer: Was there some early life event that led you to this calling?

Krassner: I was a child-prodigy violinist and at the age of six played the Vivaldi Concerto in A Minor at Carnegie Hall. A year later I saw my first movie, Intermezzo, which was also Ingrid Bergman’s first major movie, and I fell in love with the theme song. I couldn’t fathom why it felt so good to hear a certain combination of notes in a certain order with a particular rhythm, but it gave me enormous pleasure to hum that melody over and over to myself. It was like having a secret companion. When I told my violin teacher that I wanted to learn how to play the movie theme, he sneered and said, “That’s not right for you.” His words reverberated in my head. That’s not right for you. How could he know? For me, this was not merely a refusal of my request; it was a declaration of war upon the individual. In self-defense I drove him crazy during lessons, and after he died, I bought the sheet music to “Intermezzo” and taught myself to play it. That was the end of my musical career. I had a talent for playing the violin, but I had a passion for making people laugh.

A couple of decades later I heard different metaphors for that kind of experience. Timothy Leary talked about the way “people try to get you onto their game board.” And Ken Kesey warned, “Always stay in your own movie.”

Kupfer: How did you maintain your integrity as the editor and publisher of the Realist?

Krassner: I didn’t have to answer to anyone. There was no board of directors and no advertisers, and the readers trusted me not to be afraid to offend them — though sometimes they said, “Well, now you’ve gone too far.” Money was always tight, and I had to subsidize the magazine by doing interviews for Playboy and speaking at college campuses. I was forced to stop publishing in 1974 when I ran out of money, but in 1985 I got a five-thousand-dollar grant to start it up again as a newsletter, which lasted until 2001.

Kupfer: What was it like in the early days of the underground press?

Krassner: When People magazine labeled me “father of the underground press,” I demanded a paternity test. “Underground” is a misnomer, because it wasn’t a secret who published those weeklies or where you could get copies. A truly underground paper was the Outlaw, which was clandestinely published by inmates and staffers at San Quentin State Prison.

Kupfer: It seems as if “underground” publications are even more accessible today. You can get Earth First! Journal at Borders and Barnes & Noble now.

Krassner: That’s good news in terms of infiltrating the mainstream. Of course, with the possibility of Barnes & Noble buying out Borders, there may soon be one book giant: Barnes & Noble without Borders.

Kupfer: When you relaunched the Realist as a newsletter, you said in your editorial statement, “Irreverence is still our only sacred cow.”

Krassner: I’ve had second thoughts about that since then. There seems to be too much irreverence for its own sake these days. In some cases victims, rather than oppressors, have become the target.

Read the rest of this interview here/ The Sun.

Thanks to Bob Simmons / The Rag Blog

the interview only gets better as it goes along, so am suggesting reading it at The Sun link provided

– Piltz