This is an except from my new, forthcoming book about farmers, farm workers, the environment, food for the Rag Blog. — Jonah.

Field Days:

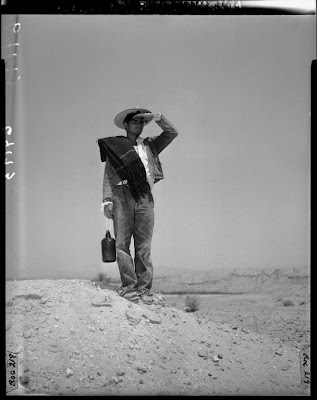

Outsiders in El Norte

By Jonah Raskin / February 6, 2009

[Jonah Raskin is a prominent author, poet, educator and political activist. His newest book, from which the following is excerpted, is Field Days. It is to be published May, 2009, by the University of California Press. Go here to learn more about the book.]

Over the past century, the plight of migrant Mexican farm laborers in California has been documented, photographed, studied, and analyzed as thoroughly as that of any other group of workers in the Americas. “What about the farmworkers?” people ask, even if they have never actually known a real farmworker. “Who are they?” “Why do they come here, and what do they want?” These are fair questions. Some of the answers to these questions are available in popular movies such as El Norte, A Day Without a Mexican, and Under the Same Moon. Steven Street’s monumental and moving Beasts of the Field: A Narrative History of California Farm Workers, 1769–1913 covers the subject magnificently. TV documentaries that expose atrocious living and working conditions provoke shock, outrage, and condemnation. Yet worker exploitation and oppression has often remained largely unchanged for decades, especially in California’s Great Central Valley.

Refugees from the so-called underdeveloped world who live and labor in the shadow of immense wealth and power, farmworkers are indispensable to the political economy of two nations. Again and again they have been pushed back and forth across borders and forced to work in mechanized agriculture and toxic environments. Perhaps this will sound melodramatic and even grotesque, but they strike me as living skeletons haunting the American Dream. Jorge Posada, the Mexican artist who saw skeletons everywhere, would certainly view them this way and depict skeletons holding hoes and planting crops. Indeed, farmwork has exposed migrants to deadly poisons.

That’s the big picture. Now, what about the lives Mexican farmworkers lead today? Could we perhaps learn something about the subject by looking at one life? I think so. Let me, therefore, introduce you to Uriel, who was born in the 1960s in the village of Chamacuaro, in the state of Guanajuato, and who now lives in Santa Rosa, California, in a multiracial working- class neighborhood. His house looks like every other house on the street, though the Obama sign on the front lawn makes it stand out. It’s the only sign in the whole neighborhood. Uriel’s story is dramatic and reflects much beyond the arc of his own immediate experience.

I’ve known Uriel and his wife, Molly, a native-born Californian, for more than a decade. I attended their wedding, and I’m an unofficial uncle to their daughter, Maya, who is bilingual and perhaps a sign of things to come in our multicultural future. Uriel and Molly exemplify the ways in which the Anglo and Latino worlds have come together to create something new and exciting. But the two worlds continue to be deeply divided. I’ve attended celebrations, for example, where Latinos, at once proud and subservient, praised their Anglo bosses, after which the same bosses, sometimes paternalistic but usually genuinely caring, praised the Latinos. And then the Anglos and the Latinos sit at opposite ends of the fiesta without any further contact. Speeches are one thing, behavior another. I’ve also been to fiestas with Uriel where one group spoke English, the other Spanish, and no one from either group reached out to the other.

It takes real effort to bridge the gulf between the two cultures, and I’ve worked at it for decades in the United States and Mexico. I’ve watched Uriel work as a mason and a tile setter, and I’ve seen him make woodcuts of César Chávez, one of which hangs on the wall above my computer. He taught me to make salsa and use words like tejolate and molcajete. Uriel is a good storyteller, too. I especially like his story about the time he tried to walk across the border on a crowded street by pretending to be a paperboy but gave himself away by forgetting to collect the money owed him. On another occasion, he and an ex-girlfriend pretended to be cachondos, two people lusting for each other. The police wouldn’t notice them, they thought, if they were kissing passionately. But they weren’t good enough at faking lust, and two California police officers sent them back across the border. Uriel made it across by climbing a chain-link fence that separated Mexico from the United States.

I’ve heard Uriel talk about his life: poverty and unemployment; hunger and loneliness; deadly rattlesnakes in vineyards where he picked grapes. But was he complaining? Maybe he was simply describing what he had experienced. In fact, Mexicans—and especially farmworkers who are illegal—rarely complain, and it can be a fault. They collude with the system that exploits them. Uriel is unique. He expresses himself and complains loudly. What I find most vivid are his accounts of his own feelings, which can be as significant and revealing as actual facts. “From the moment I arrived in El Norte, I felt like an outsider,” he told me. “I still feel that way. For years, I lived in fear of arrest and deportation. I knew that everything about me gave me away—the way I walked and talked, the clothes I wore, the expression on my face.” More than anyone else I know, Uriel helped me to understand that Mexicans often feel—and are made to feel, too—like aliens in the United States. They are the proverbial strangers in a strange land.

One warm spring afternoon I sat with him behind the house that he didn’t yet own. Possibly he never would own it, for his mortgage payment is $2,200 a month, and he hadn’t had a decent paying job in months. But he wasn’t panicking. As always he seemed cool and self-confident; having come this far in life, he wasn’t about to accept a return to poverty and homelessness, especially with another child on the way. “I feel as if I’ve struggled my whole life,” he said. “I’m struggling right now. The reason I came here—the reason every single one of us has come to El Norte—is because we have to come here to survive. We don’t want to starve to death. It’s all about work, work, work. Before I came here I was naive. I thought you could pick up mounds of money with a shovel on a street. I was rudely awakened. I jumped from job to job, and from trade to trade, to get out of the hole I was in. For years I had no steady job or work, no home, no car, no support system, and no legal status. In the eyes of America I was a nobody. Almost everyone I know has been in the same place.”

Uriel saw a lot of injustices, and he also saw that Mexicans often seemed to contribute to perpetuating the inequality between them and the Anglo establishment. They live and work largely outside the American dream, but at the same time they are living advertisements for that dream. It is ingrained in them not to dwell on their exploitation, alienation, and homesickness but instead to be positive and upbeat. “People in my village would always talk about the wonders of El Norte,” Uriel said. “They came home and boasted about the car, the TV, and the cell phone they bought. I never heard anyone say, ‘I’m killing myself in the fields’ or ‘I’m dying every day I’m at work in California.’ This was after I’d been in the United States. I had gone back to my village to visit. I would ask, ‘What about the time you were cut and bleeding from the knife you were using to harvest grapes? What about the fact that the bank owns the car you drove?’ ”

Uriel came to the United States for the first time in the late 1970s and became an American citizen in 1996. While he has made something of himself here and adapted well, he doesn’t want to end his days here, where time and money seem to drive everyone. He wants to go back to Chamacuaro in Guanajuato, where, as he put it, “never have to wear a watch or use a cell phone. I can sit and look at the church on the hill, visit with my mother, and drink a beer without having to rush off.” That Sunday, when we spoke in his backyard, I heard the longing in his voice. But of course he won’t be going home for a while. He has to find work and pay his mortgage or be out on the street.

The closest we could get to Mexico that day was a taqueria, that ubiquitous Mexican institution that can be found from Texas to Maine, California to New York. I like to think that Uriel finds solace in eating genuine Mexican food at El Patio, just a few minutes from his Santa Rosa home, but perhaps it only makes the distance from Chamacuaro feel all the greater. Eating our tacos at a table surrounded by murals of traditional Mexican scenes, Uriel remembered that as a teenager he was hungry, alone, and without a car. “I had to go miles on foot to a fast food restaurant to eat, then walk back to the apartment in the darkness,” he said. “That was a lonely time.”

Interesting read. My daughter-in-law is a doctor; she and her family came from Mexico – lovely family.

Another daughter-in-law and her parents came from Cuba; we love all of them and have learned much about their beliefs; habits, and the conditions in many parts of both countries.

Then again, I’ve seen the ghettos of New York; in parts of Cincinnati – Los Angeles….even the