Jon Melrod recalls those heady days in his new memoir.

The Port Huron Statement (PHS), which was written by Tom Hayden — with help from Al Haber and others — offered the fledgling members of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) a critique of U.S. capitalist society. Published in 1962, the year of the Cuban missile crisis, and crafted at a retreat owned and operated by the United Auto Workers (UAW), the PHS was a necessary and essential manifesto. But it didn’t present a blueprint for how students were going to challenge the “establishment,” transcend the nuclear age, and overcome the ongoing crisis of capitalism.

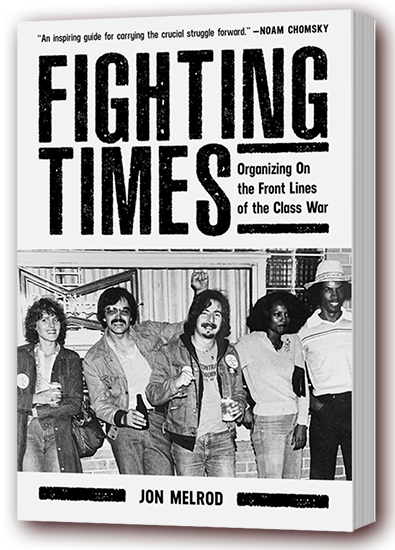

Jon Melrod recalls those heady days in his new memoir, Fighting Times (PM Press), painting a portrait of himself as a white radical, a union organizer, a journalist, and more. While he’s not the first of his generation to write about the Long Sixties, he’s one of the few to explore in depth, life in the American working class and in trade unions in the post-Vietnam era and as contradictions in capitalism and imperialism intensified. Whether Melrod is typical of those times I can’t say. Everyone was unique; no two white radicals were the same. Read on and see what you think.

(Hayden has written about civil rights and the anti-war movement. Bill Ayers, Cathy Wilkerson, and Mark Rudd have described their days as fugitives underground. Max Elbaum, a native of Wisconsin, has chronicled lefty movements of the 1970s and 1980s in Revolution in the Air: Radicals turn to Lenin, Mao and Che.)

Melrod witnessed the changing face of blue collar workers in Wisconsin.

Over the course of a decade, Melrod witnessed the changing face of blue collar workers in Wisconsin, as an older generation continued to age, and as factories and assembly lines saw the advent of more women and people of color. Their presence brought out simmering racism and sexism, which Melrod acknowledged and confronted, even as he battled for his own place among workers who were at times, anti-Semitic and anti-communist.

In 1968, Melrod was a student at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, There were few campuses more fitting than Madison anywhere in the U.S. to join SDS and become a part of the New Left. After all, it was a college town, the capitol of Wisconsin, and with a history of socialist organizations and causes.

Born in 1950 to a middle class Jewish family, Melrod became an early convert to the civil rights movement, energized by young Black men and women. At the age of 15, he joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). In Madison, he left the dorms during his first year and hunkered down in an apartment on Mifflin Street, the heart of the student ghetto, where confrontations with the cops became a routine occurrence. Melrod learned to build barricades and avoid tear gas canisters thrown into his own apartment. He joined demonstrators who opposed the war in Vietnam and was part of a successful battle against ROTC on campus.

When he wasn’t in the streets, he was in classrooms and in the library.

When he wasn’t in the streets, he was in classrooms and in the library learning about the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) aka the Wobblies, the Molly Maguires, and legendary activists such as the revolutionary Mother Jones, dubbed “America’s most dangerous woman.“

“Early on, I knew that I wanted to organize the working class,” Melrod now says. “I joined with Miguel Salas to build a union, Obreros Unidos, among Wisconsin migrant and cannery workers, many of them Texas-based Mexican-Americans, and urged consumers to boycott California table grapes. I was surprised when members of the United Steel Workers attending the School for Workers in Madison voted to join us on a picket line at the Krogers Supermarket and support the boycott.”

The year before he became a student at Madson, and when he was still in high school, Melrod had traveled to Manchester, New Hampshire, to shut down an induction center that was taking in draftees. Protesters were greeted by banners hung from an old shoe factory that read “Commies Go Home” and “Better Dead than Red.” The steelworkers in Madison showed him another side of the working class story.

“The steel workers, big beefy guys with crew cuts, took stuff from the shelves, filled shopping carts and left them at the checkout counters,” Melrod remembers. “I saw that white working class men were willing to join with migrant workers to boycott grapes and to sing the anthem, Solidarity Forever, which includes a line about bringing to birth a new world from the ashes of the old.”

In 1969, SDS broke into two hostile camps.

In 1969, SDS broke into two hostile camps, one known as the Revolutionary Youth Movement I (RYM I) and the other the Revolutionary Youth Movement II. The Madison SDS chapter initially avoided both camps, and devoted its energies to on-campus struggles against the Vietnam War and in the defense of the Black Panthers. Melrod and a team of like-minded students sold hundreds of copies of the Panther newspaper every week and supported the Black students strike on the campus in 1969.

By the end of that year, most of the members of Madison SDS followed RYM II’s political philosophy, which strongly disagreed with the Weathermen faction, and instead went into working class communities to organize. “People were in it for the long haul,” Melrod says. “It wasn’t an interregnum before going to graduate school, becoming professionals and rejoining the middle classes from which they had come.”

He added that “young organizers looked to the Viet Cong who went into rural villages and lived among the peasants.” Melrod moved to Milwaukee and rented an apartment in a Black neighborhood. When Melrod complained to the landlord about the cockroaches he was told to buy Raid and spray.

“My life changed radically when I went to work at my first factory, EZ Paintr. I had the shift from 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. and would try to sleep during the day,” Melrod says. I couldn’t complain. I had signed up for the life of an organizer.” From Milwaukee, Melrod moved to Racine where he knew no one and had to immerse himself in the local community and make friends. “I didn’t hide the fact that I was a college graduate. Nor did I hide the fact that I believed in the power of unions and the working class,” he says.

Melrod also learned some essentials from Rising Up Angry.

Melrod also learned some essentials from Rising Up Angry, the Chicago-based radical organization that recruited poor and white working class youth. “My mantra,” he says, “which I borrowed from them, became ‘learn what you don’t know and teach what you do know.’”

Melrod served as one of the editors at Fighting Times, the rank-and-file newsletter published in Kenosha by Local 72 of the United Auto Workers (UAW). The paper went after racist, sexist foremen who targeted women and Blacks. Fighting Times also launched a regular column called “Scab of the Month.” “Nothing was out of bounds,” Melrod remembers, “and no one in management or the corrupt leadership was immune to criticism and rebuke.”

Melrod and two others on the editorial board were sued for defamation of character and libel to the tune of $4.2 million. A two-and one-half week trial ensued. “It was a David and Goliath story,” Melrod says. “The American Motor Company, Goliath, financed and orchestrated the suit against us.” The dominant courtroom issue was freedom of speech in the workplace, and, while the judge was biased in favor of the company, the members of the jury, who were working class, were on the side of David.

After the not guilty verdict, Melrod continued organizing

in his UAW local.

After the not guilty verdict, Melrod continued organizing in his UAW local. Following a drastic reduction in the workforce, he stepped back from union work, went to Hastings Law School in San Francisco, and became an immigration and civil rights attorney for political asylum seekers and for families in which a member was shot and killed by the police. The murder, in 2017, by a Sonoma County sheriff of a 13-year-old Latino named Andy Lopez — who was carrying a toy gun — was the catalyist that brought Melrod back to the courtroom after a long absence. In 2004, he had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and given at most a year-and-a-half to live.

“That death sentence was unacceptable,” Melrod tells me. “I had two boys and couldn’t abandon them. I looked back at the battles I had fought against the police, against the National Guard during the war in Vietnam and against the American Motor Company, and I said to myself, ‘how much harder can it be to beat cancer?’”

Melrod launched every weapon he had at his disposal, from chemotherapy and radiation to alternative medicine that relied on herbs, diet, and exercise. Against the odds, he beat pancreatic cancer. Now he’s looking forward to the publication by PM Press of his memoir Fighting Times in which he explores his days in Madison and in Racine, the two cities that defined much of his life for more than a decade. To publicize his book, he’ll have help from “The Mifflin Brigade,” a group of former SDS members and Madison activists, who gathered together on the 50th anniversary of 1968.

Whether you were in RYM I, RYM II, part of Occupy and Black Lives Matter, or engaged in ongoing activism, Fighting Times might be the book for you. Melrod fought for the working class. He fought against capitalism, racism and sexism. His story is inspirational no matter what the color of your skin, your roots or your personal identity. “Solidarity,” he shouts. “Solidarity forever.”

To place a preorder for Fighting Times from PM Press or to read excerpts before the book is released, go here.

[Jonah Raskin is the author of For the Hell of It: The Life and Times of Abbie Hoffman. He is a professor emeritus at Sonoma State University and member of the California Faculty Association. ]

- Read articles by Jonah Raskin on The Rag Blog and listen to Thorne Dreyer’s Rag Radio interviews with Jonah.