My prison experiences caused me to understand how much I had taken on faith about administrators.

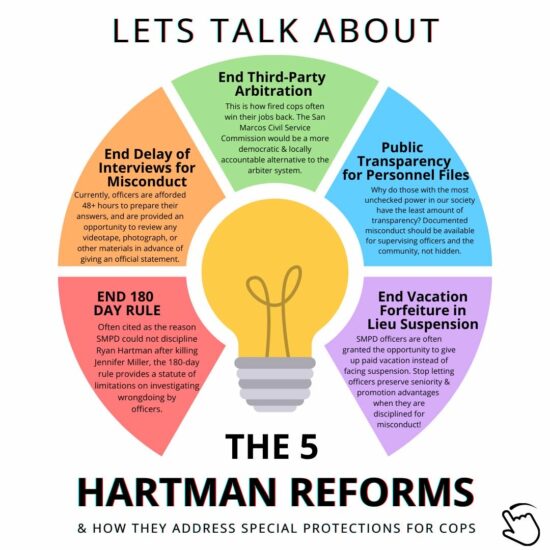

Organized troublemakers: When Mano Amiga realized that the disciplinary system for cops in San Marcos did little to protect the public, its leaders studied the deficiencies, analyzed them, and decided how best to explain the deficiencies to the public using this chart, based on an actual case, to drive home their issues. The Hartman Reforms chart explains graphically the major deficiencies in the discipline system. The chart also helped them put together a coalition of individuals, politicians, and groups to accomplish their goals.

By Lamar W. Hankins | The Rag Blog | February 24, 2023

At age 78, I continue to see the value in and the importance of being a troublemaker. I did not start out as an effective troublemaker, but I learned as I went along. These are a few of the rules that my experiences over the years have taught me.

Rule #1: Don’t trust people in authority

As a youth in the late 1950s and early 1960s, my social activities were mostly at school and church. One unsuccessful attempt to address a perceived inequality occurred when I decided that all Methodist youth in my hometown, Port Arthur, Texas, should get together for sharing, learning, and socializing. All of the predominately white Methodist churches had shared experiences periodically. We had one or two contacts with the members of the Hispanic Methodist church youth group, but proposing also to join together with the “Negro” Methodist church youth sent shock waves up and down the spines of all the adults to whom I broached the idea — our minister, my parents, and youth leaders in my church. Maybe Mexican-Americans were okay because our church had a handful of parishioners who were from that heritage, but joining together with “Negro” youth was a step too far. The adults all said “no.” (“Negro” was the term used back then, before Black and African-American became more common.)

Upon entering college at age 17, I immediately set to work to agitate for equality for all. I was successful in getting a trustee at Southwestern University in Georgetown to admit his racism by confirming that he did not want even a small number of “Negroes” at the school because he believed they would lower the quality of the student body academically, morally, and socially. I guess this racism should not have been unexpected from a southeast Texas Methodist minister of his generation, but it shocked me. The Methodist literature provided to young people by the church at that time was decidedly in favor of desegregation, several years after Brown v. Board of Education was decided, telling America to move with “all deliberate speed” to desegregate public schools. He either didn’t read the literature or couldn’t put his racist upbringing behind him to recognize the humanity of all people.

The same had not been true of the young Methodist ministers I knew from summer camps and weekend retreats. In fact, the Young Adult (college-aged youth) association of the East Texas conference of the Methodist Church managed, without interference, to integrate its meetings at the Lakeview Methodist Assembly near Palestine, Texas, within the next year. Our morals and everything else stayed intact, and we were enriched by getting to know people who had been excluded from our schools and largely from our lives up until that point.

The custodian in my dormitory at Southwestern was “Negro,” and became friends with me and another student friend who grew up in Seguin. He had a side job operating an unofficial juke joint in Georgetown, where he served beer and food, mostly to locals in his part of the community. A few students took an interest in the unlicensed establishment. My Seguin friend and I spent a few dollars there on beer and food occasionally, and enjoyed some of of the nickel plays on the juke box. I think the record Louie, Louie probably wore out during that time.

The staff refused to serve our ‘Negro’ friend.

One evening, the three of us had gone to Austin for some reason. When we got back to Georgetown, we all were hungry and stopped at a small cafe on the south side of town (I believe its name was Greenways), sat at the counter, and tried to order. The staff refused to serve our “Negro” friend, so we left and immediately started spreading the word around campus about the affront. We discussed picketing or staging a sit-in at the cafe.

We never thought about how university administrators would react to our plans, or even that they would react at all, until some of them began putting pressure on us to forget our plans. The university chaplain (and professor of religion and abnormal psychology) contacted me to persuade me that it would hurt the university’s relationship with the town if we pressed the desegregation issue. I never had any respect for the chaplain after that. We did go in the cafe one more time to test their willingness to serve “Negroes,” but the protest by students fizzled because of the pressure by administrators and faculty. That was when I decided being in authority did not mean one was right. The head of the psychology department (psychology was my minor) decided that I had a problem with authority. He was correct and he never succeeded in changing my attitude, which was reinforced many times later by the unconscionable behavior of people in authority.

The importance of Rule #1 was further impressed on me in an experience that did not involve churches or academia. In the summer of 1965, I worked as a custodial officer for what was then known as the Texas Department of Corrections, assigned to the Ferguson Unit, where young first-offenders were sent. I learned a valuable lesson in troublemaking that summer about two weeks after starting the job.

They came back with knots, cuts, and abrasion all over their freshly-shorn heads.

When four inmates under my supervision were taken to another part of the prison for minor disciplinary issues, they came back with knots, cuts, and abrasion all over their freshly-shorn heads. I asked what had happened and they told me that they were hit on their heads repeatedly with rough-hewn ax handles by some guards and prison officials for failing to work diligently.

I was not yet 21 years old and still somewhat naive about authority, especially in government institutions. On my next break, I went to the warden’s office to report the beatings. He was not immediately available, so I spoke to the assistant warden. He assured me that the four inmates were not beaten, but fell down stairs, all injuring themselves identically. I told him I did not believe what he was telling me. He then took me into the warden’s office to discuss the matter. He gave the same excuse for the injuries and I again rejected them. The warden told me to return to my work assignment while they looked into the matter further.

The next morning, I was summoned back to the warden’s office. He told me they wanted me to get a view of a wider variety of prison operations so I would have a better understanding of how the prison worked. I was then assigned to the mail room, where I would inspect all mail to prisoners to assure that contraband would not get into the prison. Occasionally, I would be pulled away from mail surveillance for an hour or two to supervise inmates while they ate in the dining hall. My job was to insure that they did not talk to one another as they ate together at tables for four. When I asked a supervisor why the inmates couldn’t talk to one another, he said “Have you ever heard a bunch of niggers yapping at one another?” Of course, the unit housed people of all races and ethnicities, but he singled out one group as an excuse. One irony (to me) was that my criminology text had a picture of the same four-person tables used at the Ferguson unit, declaring it a positive change in prison life because inmates could visit together during meals, making life more normal for them.

I learned a lot that summer — mainly not to trust prison authorities.

Near the end of that summer, I was assigned for about two weeks to supervise two inmates who worked in the farm office outside the prison walls, providing support to farm operations. Word had gotten around among inmates about my complaint about the beatings. One of these inmates opened up and told me many stories about how inmates were mistreated, beaten, and even killed by drowning in the Trinity River that ran between Ferguson and the Eastham (now named Wainwright) unit across the river. I learned a lot that summer — mainly not to trust prison authorities. I realized later that what the warden did by reassigning me was reduce the amount of casual contact that I would have with inmates. After all, in the mail room, I was reading love letters all day and censoring bra and panty ads in magazines, which kept me away from actual inmates.

My “Don’t trust people in authority” rule is a refinement of the adage “Don’t trust anyone over 30,” attributed to Jack Weinburg during the Berkeley Free Speech Movement in 1964. I thought the sentiment was worth considering, but not targeted quite right. It is not the age of the person that matters, but their role in society that is the key.

Rule #2: Know your opponent well before taking action

My prison experiences caused me to understand how much I had taken on faith about administrators. I had assumed that they were honest and trustworthy because I had not studied them well, nor had I studied the prison system adequately. My earlier criminology course about prisons had never discussed the abuse of inmates by officials or the kind of deceit by those officials I had experienced. Before trying to blow the whistle on the beatings of four inmates, I had no idea that such beatings were a routine part of the prison culture, inflicted with the approval of the warden and other high officials. For all I knew, the beatings could have been sanctioned by the head of the prisons at the time, a former Lutheran minister, George Beto.

Fifteen years later, after becoming an attorney, I found out that both the warden and assistant warden had prospered in the so-called criminal justice system. The warden had become a high official for the Texas Department of Corrections when I saw him testifying on prison funding before the Legislature; the assistant warden became one of three parole officials in the state who assessed prisoners for release on parole (I appeared before him several times on behalf of parolees, but I never knew whether he remembered me).

About 1967 or so, I began studying the teachings of the well-known community organizer Saul Alinsky. I even attended a private workshop with Alinsky in Austin around 1970, when I was working for a social service agency. In some ways, I regret not joining up with his organization before I set off on the path my life took. But I did learn from him that it is essential to know one’s “enemy”; that is, find out as much about an opponent as can be learned before deciding on a course of action to correct some social or economic injustice.

A relatively new organization in San Marcos, Texas, that has taken this rule to heart is Mano Amiga, run by mostly young people. In just four or five years, it has succeeded in bringing about many changes to correct injustices. Its members studied the arrest and detention process before campaigning for an ordinance (approved in a referendum) that requires the police to cite and release, rather than arrest, people charged with minor offenses, thus helping many people avoid sitting in jail because they can’t afford to pay a bail bond business to get them released until their day in court.

Mano Amiga learned about another need when the Covid-19 pandemic hit. It began providing a home delivery service (with financial support from Hill Country Freethinkers Association) in a cooperative arrangement with the Hays County Food Bank for low-income folks who could not attend food delivery distributions because of mobility or health problems, or a lack of transportation.

Other problems in the criminal legal system came to the attention of Mano Amiga.

Other problems in the criminal legal system came to the attention of Mano Amiga and it responded. The organization was a major player in getting the Hays county Commissioners Court to fund a $5 million public defender program for the county. And in 2022, it succeeded in passing a referendum that decriminalized cannabis possession in San Marcos with 82% of the vote.

Through another referendum Mano Amiga successfully challenged the contract between the City of San Marcos and its police based on an ineffective disciplinary system provided in the contract. That issue will be on the ballot later this year to allow voters to decide if they want the police held accountable for misconduct in a more effective way.

In each case, Mano Amiga learned about a problem, studied it, analyzed the decision-makers, decided on their best arguments to reach their goals, and formulated a plan to succeed in their efforts, always putting together a coalition of individuals, politicians, and groups that had influence in the community.

Rule #3: Assume that all people in positions of authority lie

It was I. F. Stone who said, “All governments lie.” The corollary is that all persons in positions of authority probably lie. It is best to take the word of a known liar and “trust, but verify.” I’ve worked with a few people in positions of authority who did not lie, so far as I know. But these people are rare. Misleading, obfuscating, and stonewalling are common practices to look for when dealing with people in authority.

Skepticism is always the right attitude to take when dealing with authority figures.

Skepticism is always the right attitude to take when dealing with authority figures. When they make a claim, challenge them to show you the evidence. Often, they won’t be able to do so. And keep in mind that what they call evidence may be just a smokescreen to hide the truth, so examine their evidence to see if it really is evidence.

One of the most frustrating problems with lying, misleading, obfuscating, and stonewalling lies with our politicians — some of our least accountable authority figures. About 40 years ago, Rep. Phil Gramm, before he became a senator from Texas, represented a congressional district in the Bryan-College station area, where I lived while my wife was in graduate school at Texas A&M. Gramm periodically held public events with his constituents, who were allowed to ask him questions. I formulated some pointed questions that I wanted answers to and learned that Gramm handled questions he did not want to answer in several ways: he answered some other related question that he preferred; he refused follow-up questions; he obfuscated in his response; he lied by misleading in his response; he said he would have to get back with the questioner about that matter, although usually he had no idea who the person was or how to contact them. But he could always say publicly that he had community forums to talk with his constituents about the issues.

Gramm’s way of handling issues of concern to the voters undoubtedly has been used by countless politicians before and after his reign as a Texas politician. So remember, assume that people in positions of authority lie, one way or the other.

Rule #4: Don’t let authority figures frame the issues

Those in positions of authority will always frame issues to their advantage. For example, with respect to Mano Amiga’s effort to subject police officers to better disciplinary processes in San Marcos, the police and other authority figures will want to frame the issue to make people believe that the issue is supporting the police by upholding a contract between them and the city because we owe these public servants the protection afforded by what amounts to a collective bargaining agreement.

Of course, that is not the real issue. Mano Amiga is not opposed to a collective bargaining agreement for police. They want such an agreement to provide for a disciplinary process that will be fair to both the police and the public. As it stands now, misconduct by a police officer may not be investigated by the police department until after the criminal legal system has investigated, a process that may exceed the 180 day time limit on taking disciplinary action. What Mano Amiga wants is for the department to conduct its own immediate investigation without regard to what the legal system does. While other issues may be involved in this referendum, this is an important one.

Always frame issues from your perspective. After all, it is the citizen’s perspective that is most important.

Rule #5: Find allies

The importance of finding allies may seem self-evident, but far too many people and groups fail to reach out to others for support. Alinsky’s community organizing from his beginning in the Back of the Yards area of Chicago (as described in his book Revielle for Radicals, published in 1945), involved putting together allies to have the strength to achieve a common goal. His 1971 book Rules for Radicals is also important reading for people who want to make the world a better place for those without power and resources. Mano Amiga found that allies working together to reach a common goal is a crucial component of a successful strategy.

Whether you are young or old, if you want to help change this world, you need to know how to effectively approach the problems that concern you. There is much to learn, and I continue in the quest for that knowledge. I have learned more from studying Alinsky’s understanding of the world than I have from almost any other individual.

Admittedly, I have a problem with authority, but I don’t see that as a psychological defect. If you care about justice and equality, you have to question those in authority. If you do so effectively, you may be able to change a few things that need changing. But nothing ever stays changed; nothing is ever finally settled. Maybe that suggests the next rule. To paraphrase Thomas Jefferson, “Eternal vigilance is the price we pay to have a more just world.”

[Rag Blog columnist Lamar W. Hankins, a former San Marcos, Texas City Attorney, is retired and volunteers with the Final Exit Network as an Associate Exit Guide and contributor to the Good Death Society Blog.

Read more articles by Lamar W. Hankins on The Rag Blog and listen to Thorne Dreyer’s Rag Radio interviews with Lamar.

Lamar— thanks for recounting some of your experiences as a young adult. It’s always fascinating, and I always learn something from these stories.

There are a lot of people around our age associated with the Rag Blog, and I hope we all continue to be troublemakers in one way or another!

The article about “woke” by Lamar interested me because it’s something I’ve been thinking about. I’m glad that he covers the topic with at least some reservations about the phenomenon, including some doubt about the value of “trigger warning.” It was good to point out that the concept of being “politically correct” caused some resentments, and “woke” is doing the same. I think “woke” is more problematical than Lamar does. I find the “woke” people to be almost like a cult, people who see themselves of superior because they are “woke.” I am “aware.” That’s good. Some people are unaware (victims of misinformation, etc.) That’s bad. Why do we need the word “woke” when we already have the word “aware?” The “woke” people can be horribly intolerant and impatient, putting themselves on a pedestal of alleged superiority. I know a college professor, a very decent human being, who was hauled before a dean because he “misgendered” someone. That did not help my college professor friend become better informed about transgenderism. He felt humiliated, then became angry, and I don’t blame him.