September 11, 2023, marks the fiftieth anniversary of the 1973 military coup in Chile.

By Alice Embree | The Rag Blog | September 10, 2023

The Austin Committee for Human Rights in Chile began after the coup. It is where I deepened my understanding of U.S. complicity in that coup. It’s where I was called Compañera, where I met a partner who had been in Santiago that fateful day. The long shadow of dictatorship, lasting 17 years, marked my life and others I came to know in the Chile solidarity movement. Our solidarity efforts echo a previous generation’s experience with the Spanish Civil War and its aftermath, a long shadow of dictatorship.

As we live in a time of peril, climate apocalypse, state bans on bodies, local bans on books, and sustained attacks on democracy, I can’t help but feel we are on a precipice. Imbued with remembrance of movement victories and a sense of solidarity, we live with a palpable fear of losing ground, of losing democratic rights we thought were inalienable.

I was moved by Ariel Dorfman’s recent article, “Defending Allende,” in the New York Review. He was there when Allende won the presidency. He speaks of it beautifully:

I had one of the most moving epiphanies of my life on the night of Allende’s election on September 4, 1970. After listening to him promise a delirious crowd that he would be el compañero presidente when he entered La Moneda in two months’ time, I wandered along the streets of Santiago with my wife and friends and witnessed the wonder, pride, and determination on the faces of workers and their families as they walked through the center of the city.

He writes a more somber memory of the mobilizations three years later, September 4, 1973, a week before the military coup. The crowds chanted, “Allende, Allende, el pueblo te defiende.”

Ariel Dorfman does not limit himself to nostalgia for the victories, or somber reflection on the losses. His provides a sweeping story of the long saga of dictatorship, the return to democracy, the euphoria of the recent presidential victory of Gabriel Boric, the excitement kindled by creating a new constitution, and the whiplash rise of a right-wing forces able to defeat the constitutional referendum.

Even with the gains and losses, Dorfman ends with a defense of Allende’s legacy:

The wounds of Chile are deep, but regardless of how Chileans decide to deal with our trauma and conflicts, Allende’s legacy might have some bearing beyond the borders of his country. The need for radical change through nonviolence that this unique statesman posed—and did not achieve half a century ago—has again become the crucial issue of our era. With new variants of Pinochet troubling so many lands, Allende’s insistence throughout his life that for our dreams to bear fruit we need more democracy and never less—always, always more democracy—is more relevant than ever. He calls out to us that there can be no solution to the dilemmas plaguing the planet—war, inequality, mass migration, the twin threats of climate change and nuclear annihilation—without the active participation of vast majorities of fearless and enthusiastic men and women marching past the balconies of the future.

Fifty years after his death, Salvador Allende is still speaking to us.

People’s History in Texas posted a related story on Substack. It is about the Bread and Roses Center, a project of the Austin chapter of the New American Movement, and a direct action that galvanized a Chilean solidarity movement in 1976. I was one of the people pulled off a stage while protesting CIA director William Colby. As several of us were ushered out the back door to police cars, we sang “Solidarity Forever” loudly enough to be heard throughout the auditorium.

Bread and Roses: Incubator of Chile Solidarity

In 1976, the Austin chapter of the New American Movement (NAM) opened a community center in the west campus area. Its name was the Bread and Roses School for Socialist Education. One of the project coordinators was Glenn Scott, who was a founder of People’s History in Texas as well.

Bread and Roses looked like a regular house until you walked inside. A Puerto Rican artist Carlos Osorio was artist in residence occupying the front foyer. A small bedroom housed a women’s print shop, the Fly By Night Printing Collective. The press occupied most of the floor space. A NAM member and University of Texas shuttle bus driver, David MacBryde, lived in the back. The living room provided ample room for social gatherings and classes.

A “World Revolution Forum” with sessions devoted to a number of countries including Chile was on the schedule of events. To be clear, in 1976 Chile was a better example of counter-revolution than revolution.

In 1970, Salvador Allende had been elected president of Chile. Allende was a socialist, a doctor, a former senator, and a former cabinet minister who had run for president twice before. During his presidency, Chile made many changes to address poverty, expand national healthcare, empower workers, and transform Chile’s lucrative copper mines from sources of private profit to the national necessities of a socialist democracy.

A socialist victory — by electoral means — was intolerable to the Nixon administration. The United States spent three years destabilizing the Chilean economy and covertly murdering key allies of the presidency, including military officers who would have supported constitutional democracy.

But, Allende’s government proved more popular in each election cycle. Finally, on September 11, 1973, a military coup took place. The national palace was bombed. A military dictatorship consolidated its power and used economists trained at the University of Chicago, the “Chicago Boys” to overhaul the economy, removing the vestiges of social democracy, and privatizing public sector services.

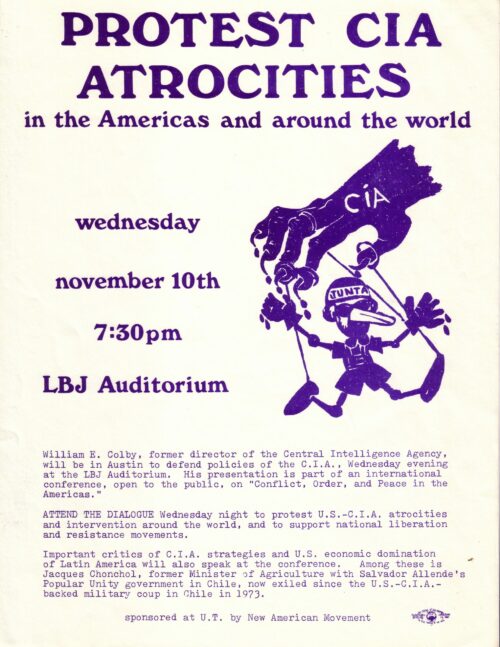

In 1976, with the dictatorship firmly entrenched, there was a gathering at Bread and Roses and a call to action that galvanized Austin solidarity efforts. A Chilean alerted people to an upcoming event at the University of Texas LBJ Library. A conference on “Conflict, Order, and Peace in the Americas,” would include two participants of note. The former CIA Director William Colby would be in attendance as well as a neoliberal economist, Arnold Harberger, who was one of Chile’s “Chicago Boys.”

A NAM leaflet called for a protest of CIA atrocities at the event. Several people were arrested after mounting the auditorium steps to hold a banner close to William Colby. Another group, seated in the middle of the audience, called for a moment of silence for those who had died in Chile as well as for Orlando Letelier, a former ambassador from Chile, and his colleague, Ronni Moffitt, who had been assassinated by a car bomb in D.C. on October 21, 1976.

The protest and the arrests sparked solidarity efforts in Austin, with the Austin Committee for Human Rights in Chile created as a result. The Chile Committee held regular meetings at Bread and Roses and hosted cultural and educational events there called Peñas, fashioned after the Peña de los Parra in Santiago.

The committee brought Chilean musical groups, who were living in exile, to Austin venues including the Armadillo World Headquarters and Liberty Lunch. The committee carried out boycotts, lobbied Congress, sponsored action, and kept the spirit of Chile solidarity alive until a 1988 plebiscite paved the way back to constitutional democracy.

The 50th anniversary of the military coup in Chile is September 11, 2023.

[Alice Embree is an Austin writer and activist who serves on the board of directors of the New Journalism Project, is associate editor of The Rag Blog, and was a founder of The Rag, Austin’s legendary underground paper, in 1966. Alice’s memoir, Voice Lessons, was published by the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History and distributed by the University of Texas Press.]

Important events and an important benchmark in our social struggles, but here’s my question for today’s activists: why are the US State Department, the CIA, and the ‘Defense’ Department hacks seen by many as truth-tellers in the war in Ukraine? We know from coups and wars before the Chilean disaster, plus coups and wars since then, that these agencies – with cover from their sycophants in the MSM (and Congress) lie, cheat, and steal (per Mike Pompeo) – not to mention murder, torture, extort, bribe, and generally create mayhem. What makes anyone think – or even hope – that this is somehow not the case now?

Thanks, Alice

Thanks so much for this, Alice! I had been looking for something to post on my Facebook page about the 50th anniversary of the first 9/11, and you’ve given it to me. I also posted it to an email list with some old comrades and a few newer ones too. Some of these folks were involved in Latin America solidarity efforts in the 1970s and 80s (and in campaigns against apartheid in South Africa).

I love it when you write about your experiences. Learn something new every time. We don’t want to forget.

Thanks, Alice, for the remembrance and the call to action for more democracy now!

Bread & Roses was one of the most influential projects undertaken by the New American Movement. I attended many meetings and social gatherings there. It was at B&R that I got to know David MacBryde, the bus druving/cabbie Philosophy grad who was s tireless advocate for human and civil rights, for labor and education, and who brought a unique brand of good cheer to any endeavor.

Dave served with distinction on the Board of Directors if Youth Emergency Services, Inc. (Phogg Phoundation for the Pursuit of Happiness). He fully exemplified the Phogg program of “Good Times for a Better Community., and like the inimitable Glenn Scott, is greatly missed.

David MacBryde and Pat Cramer, dearly departed, were both among those arrested at the Colby event protesting the CIA’s involvement in the coup. Both were in NAM and shuttle bus union activists.

David Duhalde, of Democratic Socialists of America, wrote a piece for Jacobin on the U.S. Socialist response to the coup. It mentions Bread and Roses and the Austin Committee for Human Rights in Chile.

https://jacobin.com/2023/09/chile-coup-allende-dsco-nam-democratic-socialists-america-aoc?fbclid=IwAR0ZcXRBE4Cp-1V2adue6psUmHL5X2-fSl5gBbZvRHiBrFeGduZf69zGu

The silk-screened posters of the Austin Committee for Human Rights in Chile can be viewed at this site: https://collectiveimpressions.wordpress.com/2023/09/12/austin-committee-for-human-rights-in-chile/

Collected Art of Solidarity, edited by Alice Embree and Carlos Lowry is available at Lulu.com The posters and leaflets of the Austin Committee for Human Rights in Chile are included in this 96-page book. https://collectiveimpressions.wordpress.com/2023/09/12/austin-committee-for-human-rights-in-chile/