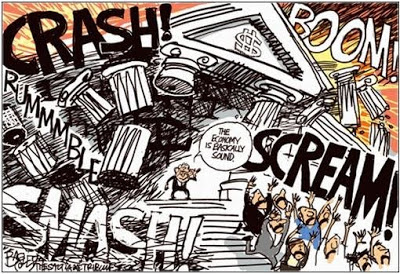

‘We can now observe that the creation of unlimited credit by unregulated investment banks, together with peak/near peak oil causing a steep oil price rise, is together enough to trigger a panicky deflationary spiral that has its own complex dynamics.’

By Roger Baker / The Rag Blog / November 10, 2008

See ‘Beijing holds key to prosperity’ by Henry C K Liu, Below.

Fossil fuel limits are an important key to insight, but are not sufficient for understanding the current world economic crisis.

Future oil production can be calculated almost with the precision of the laws of physics. The world is now about to decline in the production of the vital fluid that powers almost all world transportation, with no viable replacement available any time soon.

This predictable causal factor is in sharp contrast to its consequences; the impact of fossil fuels limitation in affecting the global economy. Here more traditional economic thinking can still be helpful in filling out the details of how events are likely to play out.

I will list some examples of sources that are both conscious and unconscious of peak oil, but all of which are useful, in my opinion.

We can now observe that the creation of unlimited credit by unregulated investment banks, together with peak/near peak oil causing a steep oil price rise, is together enough to trigger a panicky deflationary spiral (read run on the world’s banks) that has its own complex dynamics. The economic results are partly due to mass psychology and are accordingly hard to predict.

A useful source of economic insight from a social impact perspective is Loretta Napoleoni’s “Rogue Economics,” which anticipates and documents a global rebirth of decentralized grassroots tribalism as a result of the current unregulated and rapacious corporatism. She may be right, and this is an important concept linking economics, politics and sociology.

One clearly observable economic pattern is that oil now acts as an economic limit to the expansion of the global economy. If and when the global economy recovers, oil prices will soon rise enough to restrain the recovery, much like the automatic governing mechanism of a classic steam engine, when it is set so as to increasingly restrain its top speed.

…In the three-way struggle among worldwide oil depletion, new oil production projects, and the global recession, we have a pretty good handle on depletion and new projects, but appreciation of the depth and length of the recession is not well understood. What was widely believed last year to be a couple of weak quarters is now generally acknowledged to be the worst economic slump since World War II. Optimists, especially on Wall Street and in Detroit, are saying that by 2010, or 2011, or 2012, the recession should be over and economic growth will return. There is great faith that the world’s governments can manage a recovery by lowering interest rates, pumping trillions of government money into the financial system, loaning money to failing corporations, and instituting massive stimulus packages. Some are not so sure…

There are many good economic analysts on the internet, and a growing minority now see the big picture in a way that incorporates peak oil. The Post Carbon Institute is a leader in providing good big picture information.

Check out their “Reality Reports” and the splendid economic lecture series by Chris Martenson. Here is one interview with Martenson.

Check out ASPO-USA . And also the Oil Drum and Energy Bulletin.

Here are a few other fossil-fuel-conscious sources I like: Matt Simmons; Jim Paplava, et al of Financial Sense; and James Howard Kunstler .

That said, it is also important to understand the valid conclusions of the best economists who do not focus much on the economics of peak oil. Some of the best independent reporting and geopolitical and economic analysis is to be found on the Asia Times Online website. It is the first place I turn for good independent reporting on affairs in Asia and the Mideast, although its writers are not always in agreement:

Here for example is a piece explaining the poor ability of classic Keynesian economic stimulation (like that now being advocated by Paul Krugman) to revive the US economy. The economic crisis is global in nature, so US-based remedies are not a good match, but there are other problems. See this and other stuff by David Goldman on the ATO blog.

To my way of thinking, Henry C. K. Liu is one of the keenest economic observers anywhere. Asia Times Online archives much of Liu’s writing.

Below Liu says that China and its acceptance of non-market based economics is the key to any potential global economic recovery. To save the global economy and to keep it from getting dragged down into the unregulated quagmire the investment banks have generated, the Chinese will have to dump market capitalism. Here are some details, by Henry C.K. Liu, from the last part of a much longer two part article, typified in its thinking by this snip:

…China’s ability to rescue the stalled global economy through reform in trade is extremely limited. The best way for China to contribute to stabilizing the world economy is to develop the country’s domestic market and to increase the purchasing power of the population through a progressive income policy with full employment. It fact, China needs to adopt a bottom-up development strategy of direct assistance to people, the opposite of the US top-down development strategy of

assistance to institutions…

China and the Global Crisis:

Beijing holds key to prosperity

By Henry C K Liu / December 6, 2008[….]

…China needs to recognize that market capitalism with central banking is not the most effective or efficient system to achieve full employment with rising wages. China needs to adopt a full employment policy as a national objective. A socialist system must provide every able citizen who wants to work opportunity for work. China is still grossly underdeveloped economically. With so much to do to bring China into a modern nation, it is hard to imagine a country like China not having a labor shortage. China must create an economic system that puts full employment as a top priority, not allow itself to be trapped by neo-liberal market fundamentalism of using unemployment to keep wages low to protect the value of money.

What China must do

With recurring capitalistic market crashes, the world is beginning to realize that market capitalism can destroy wealth as fast as it can create wealth. While keeping markets as an auxiliary mechanism for efficient allocation of resources, China must rely on central planning to direct investment in an orderly manner in sectors need for national development, such as modernization of food production and distribution. It must rely on planning to direct investment towards physical and social infrastructure, in universal education and universal health care. These investments must be increased and accelerated with much higher targets for each five-year plan.

To do this, China must develop more respect for and reliance on domestic indigenous talent and make more opportunities available to young people. Brain drain is the greatest loss China has suffered in the past century. In recent years, a massive loss to other countries of well-educated people has blighted the Chinese finance sector. Chinamust develop policies to stop further brain drain and to revert the flow of human resources back into China.

China must invest more on domestic development than on exports, particularly on rural development. It must not look for growth through cross-border wage arbitrage by foreign capital. Wage income is the only reliable index of growth for any economy. Export-led growth is unsustainable for meeting the needs of an economy that comprises one fifth of the world’s population, particularly when export earning is denominated in fiat dollars that cannot be spent in China domestically.

Modernization is not merely blindly copying the advanced economies. China must avoid excessive faith in market forces while taking care not to ignore them. It must set a framework in which market forces that create benefits for the community are encouraged and those that create costs to community are penalized.

At its root, China is an agricultural economy. Chinese leaders have depicted the new socialist countryside program as having higher productivity, improved livelihood of farming families, a higher-degree civilization with greater socialist ethics, a clean environment and democratic management in the 11th Five-Year Program (2006-2010) period, showing the resolve of China’s leadership to spread the fruits of reform to its rural areas, especially poor regions.

The central government allocated 13 billion yuan in 2007 to its poverty reduction program, 13 times that in 1980 and 37.2% of which was earmarked for the autonomous regions of Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Ningxia, Guanxi and Tibet, and provinces with large ethnic populations, such as Guishou, Yunan and Qinghai.

While this a good start, it is woefully inadequate. What is needed is 100 times the amount ($160 billion) every year until these regions reach self-sustaining prosperity. After all, a nation that holds close to $2 trillion in foreign exchange reserves, should not tolerate poverty anywhere within its borders.

After more than 30 years of economic reform, the poverty rate in rural areas has dropped to less than 3%. But that still leaves 40 million poor due to China’s big (1.3 billion) population. China also has 26 million people who live at subsistence level beyond the reach of the poverty reduction program. The Chinese government has turned more attention on its rural poor by reducing various taxes and promoting free universal compulsory education. The agricultural tax, which has had a history of 2,600 years, was rescinded completely in 2006 and an increasing number of children in rural areas gained access to free compulsory education.

China also has begun to lower the price of medical services by reinstituting a rural cooperative medical service system. Still such a timid anti-poverty program for the world’s largest creditor nation is a glaring contradiction. Yet this program is too timid in allowing poverty to continue to be a drag on economic growth.

China has since unveiled ambitious plans to help the 800 million people living in the countryside catch up economically with city dwellers. More rural investment and agricultural subsidies and improved social services are the main planks of a policy to create a “new socialist countryside,” which President Hu has declared as a national priority.

The new policy regards constructing a new socialist countryside an important historic task in the process of China’s modernization. “The only way to ensure sustainable development of the national economy and continuous expansion of domestic demand is to develop the rural economy and help farmers to become more affluent,” the policy asserts. It aims to modernize the countryside, which has fallen behind in China’s development in recent decades.

From 2006 until 2010, the government promises sustained increases in farmers’ incomes, more industrial support for agriculture and fasterdevelopment of public services. Yet current plans remain timid in relation to the size of the problem and must be redoubled to prevent rural poverty from emerging as a drag on national economic development.

Local governments have been warned that they will be held to account for ineffective administration and misallocation of precious resources on false symbol of prosperity. The new measures promise greater protection and improved democracy in rural areas, and local government bureaucracies will be streamlined to increase cost effectiveness. Instead of gauging progress by GDP growth, attention should be paid to income growth, particularly farm income growth. Income is all; without income, all else is mirage.

In part, the new socialist countryside policy is driven by concerns about China’s ability to sustain food self-sufficiency going forward as a global crisis of food is fast building. The past 25 years of rapid urbanization have seen much farmland turned into urbanized development zones, and more than 200 million farmers have migrated to the cities to serve export sector needs.

The new food policy proposes that China should remain “basically self-sufficient” in grain. It promises increased subsidies for farmers growing grain, as well as continued revenue “bonuses” for local governments in the grain belt, and says the government will continue setting minimum prices for grain purchases.

With 800 million people living in the countryside, the only way to ensure sustainable development of the national economy and continuous expansion of domestic demand is to develop the rural economy and help farmers to become more affluent than city dwellers to reverse the migration trend. The program also stressed that construction of the new countryside should focus on practical development and involve democratic consultations. Most of all, ample farm credit must be provided by the central government to help poor rural region to kick start development.

Chinese agriculture is at a crossroads as the benefits of the agricultural changes first ushered in late 1978 have lost momentum. Grain production, which reached record levels in 1984, dropped suddenly in 1985 and is only now beginning to push above 1984 levels. The area under cultivation, already small compared with the population, is steadily declining as new housing, schools, factories and roads nibble away at rice paddies and wheat fields. State investment in agriculture has dropped precipitously over the past two decades.

China’s exposure to the international financial crisis is primarily a result of its high dependency on exports, which in turn is the result of high dependency on financial market forces to allocate the use of capital, particularly foreign capital.

Markets seldom direct resources where they are needed, only to where profit is easiest and highest. Market forces when unregulated and undirected always lead to uneven and sometime undesirable development. Much of China’s economic dilemma today is the result of blind acceptance of the Hayekian efficacy of market forces. The reliance of a labor market to direct economic development is counterproductive. China needs to understand that labor is not a commodity but a national resource. The value of labor should not be allowed to be set by supply and demand in a labor market. It should be set by national policy around which markets are organized to fulfill it. This is the fundamental flaw of China economic reform for the past three decades.

China’s ability to rescue the stalled global economy through reform in trade is extremely limited. The best way for China to contribute to stabilizing the world economy is to develop the country’s domestic market and to increase the purchasing power of the population through a progressive income policy with full employment. It fact, China needs to adopt a bottom-up development strategy of direct assistance to people, the opposite of the US top-down development strategy of assistance to institutions.

This means a strategy to set the increase of personal income and social benefits as a goal around which the economic system is organized, rather than letting personal income and social benefits be the outcome of imported dysfunctional economic systems such as predatory neo-liberal cowboy market capitalism.

[Henry C K Liu is chairman of a New York-based private investment group. His website is at http://www.henryckliu.com/.]

Source / Asia Times Online

I am quite deficient in understanding of economics, at both macro and micro levels, but I have what I guess I can only call an intuition that capitalism is not the ideal economic system and that some form of socialism, or something very close to it, is.

I once tried to take economics as a post-bacc class in the early 90s, and it seemed too focused on capitalism/markets, and consequently, it seemed off-base to me and I couldn’t get into it enough…and I dropped it. So, it is very interesting to me to see economists and others who are very well-versed in the subject (especially someone who might be “chairman of a New York-based private investment group”) write things like:

“Markets seldom direct resources where they are needed, only to where profit is easiest and highest. Market forces when unregulated and undirected always lead to uneven and sometime undesirable development.”

or

“must create an economic system that puts full employment as a top priority, not allow itself to be trapped by neo-liberal market fundamentalism of using unemployment to keep wages low to protect the value of money.”

On a slightly different topic, I found it interesting to read:

“The new measures promise greater protection and improved democracy in rural areas”

and

“The program also stressed that construction of the new countryside should focus on practical development and involve democratic consultations.”

Of course, we rarely hear about democracy and socialism working together in this country, but it has always seemed to me that you can’t really have one without the other, or at least that either one without the other will be a perverted and inadequate version.

I neglected in my own smart list of notable economists Richard Heinberg, now a fellow with the Post Carbon Institute, who writes Museletter.

Actually Heinberg is not a credentialed economist. Most of those kind of economists are no good; they have been required as part of their training to believe that there are no natural limits on growth. Thus it takes a non-economist’s vision to see clearly through the capitalist hype assuring the righteousness of exponential growth forever:

http://www.richardheinberg.com/museletter

Just below is a link to a singularly useful Heinberg Museletter explaining what Obama needs to do now, insofar as rational minds and policies can prevail (which in itself seems like a stretch, so I hope readers agree we each have a secular humanist responsibility to do our best to change that; a big part of the problem is that we are going to have to rebuild our faltering economy without cheap oil; we clearly can’t tolerate the curse of bad planning).

http://globalpublicmedia.com/memo_to_the_president_elect

Heinberg wrote what is now a classic about peak oil; “The Party’s Over”. I think he was partly influenced, like me, by hanging out on Jay Hanson’s Energy Resources list almost a decade ago.

A little background; Jay Hanson was and is a sort of aggressive intellectual pessimist, a pledged enemy of economists in general. But Hanson did like certain economists like Polanyi, who I also like. And whom I think offers certain insights; ones that did not occur to Marx or the Marxists who had influenced my own thinking long ago.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl_Polanyi

Hanson regularly trashed the techo-optimists in fair open debate on his lists. An ability achieved through his being enormously thoughtful and well-read (see the dieoff.org website). I regard Hanson as an irascible (in print only from what I understand) and iconoclastic genius who helped revive a lot of the limits-to-growth thinking characteristic of the earlier energy crisis of the 1970’s. This was back when this thinking was fresher and was not considered so subversive of corporate expansionism as it was to become under Greenspan, etc.

The book “The Limits to Growth” was popular in the later 1970’s, but was anti-capitalist. Then William Catton wrote “Overshoot” in the early 1980’s, which is almost poetic in style; a classic. Incidentally, a great uncut Catton You Tube-like interview is available on the Internet:

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=-4171942672579965146&ei=Z1K0SOj7PKDAqwPVqKzLDA&q=William+R.+Catton%2C+Jr.

But back to Heinberg. I have reposted some of Heinberg’s stuff before on The Rag Blog.

http://theragblog.blogspot.com/2008/05/adapting-to-peak-oil-hard-way.html

Heinberg is a smart friendly guy you can read on his Museletter site for free. Then you can often meet him in person at the yearly ASPO-USA conferences (you can meet and listen to lectures by many of the best and the brightest minds anywhere on energy policy, at both the international and US yearly ASPO conferences).