Can the Democrats sweep Houston? (Maybe. But don’t hold your breath…)

By Dave Mann

This article appears in the Oct. 17, 2008, issue of The Texas Observer.

You normally don’t think of Houston as a bastion of Democratic Party politics. For years the city has been dominated by the oil industry and the GOP—they’ve often seemed one and the same. Houston gave us George H.W. Bush, Tom DeLay and Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst, and some of the nation’s most prolific Republican campaign donors call the city home.

Democrats are hoping to overcome that profile. They’re pouring tons of money into a campaign to transform the Houston area into a Democratic stronghold they hope will help swing future state and national elections. Their goals aren’t small. Many within the party believe Houston is the key not only to recapturing Texas for Democrats but also to putting the state back in play in presidential elections. All of which makes Houston one of the most important battlegrounds in the country this year.

That may sound grandiose, but to understand the Democrats’ strategy, you have to consider that Houston is essentially its own swing state within Texas. Harris County, which encompasses the city and its suburbs, is home to 3.9 million people, outnumbering the populations of 23 states, and is roughly the same population as Oregon. Now consider that Harris County—in theory, at least—is already Democratic. Surveys and polls repeatedly show that more of its eligible voters identify with Democrats. It’s just that many of those people don’t vote. Moreover, the area is growing. Subdivisions are sprouting at the city’s edge like weeds. The people moving in are mostly Democrats. Harris County is undergoing a demographic shift that will soon put Anglos in the minority.

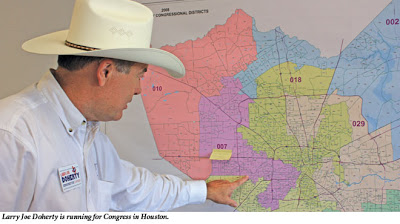

Practically speaking, a Democrat can’t win a statewide race in Texas without carrying Harris County. If the party can increase its turnout just enough in this presidential year to turn Harris County blue, Democrats will control five of the state’s largest counties and could become competitive again in races for governor, lieutenant governor, and U.S. Senate. Democrats are feeling the urgency to capture a statewide race and at least one chamber of the Texas Legislature by 2010 to gain a say in the next round of legislative and congressional redistricting.

But Houston’s size and shifting demographics have local Democrats dreaming well beyond the Governor’s Mansion. They talk of a day when Houston could be for Texas what Philadelphia has been for Pennsylvania—a metro area that votes so overwhelmingly Democratic it provides a large enough advantage to deliver the state almost by itself. (In the 2004 election, Philadelphia handed Democrats a 400,000-vote edge in the state’s largest population center—a margin Republican areas of Pennsylvania couldn’t surmount.)

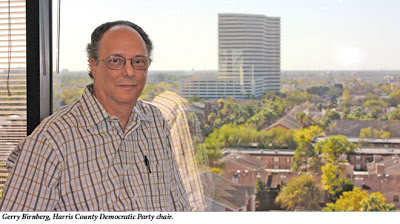

Harris County Democratic Party Chair Gerry Birnberg points out that if big margins in Houston could help a Democratic presidential candidate capture Texas, the Electoral College map would shift decisively. He says New York and California likely will vote Democratic for a generation. “If you can start a presidential cycle with California, New York and Texas already in your column, there is not an electoral map you can draw that a Republican candidate can win,” Birnberg says. “Harris County is ground zero. We don’t get there without Harris County.”

Democrats have never lacked for grandiose plans. Execution is usually the problem. In the here and now, Harris County Republicans still hold every county office and every district judge position. The GOP has carried Harris County in every presidential election since 1964.

For the past two years, though, local Democrats have worked toward flipping Harris County in 2008. They’ve recruited more candidates than ever before, raised money specifically for the effort, and designed a comprehensive campaign that coordinates the state and county party apparatuses with candidates on advertising, voter registration, and get-out-the-vote operations.

At the same time, circumstances seem to have conspired to favor Democratic gains. Corruption scandals engulfed a county commissioner, the county judge, the sheriff, and the district attorney (who eventually had to resign)—Republicans all.

And in March, the Democratic presidential primary ignited unprecedented voter interest and turnout, which seem likely to carry over into the general election.

It all seemed like the proverbial perfect storm to sink Houston Republicans in 2008—that is, until a very real storm arrived September 12. Hurricane Ike devastated the area, knocking out electricity for nearly three weeks in some neighborhoods. The storm and its aftermath precluded weeks of campaigning and voter registration, a period when no one, including campaign staff, was thinking about politics—the sort of interruption that typically benefits an incumbent.

If Democrats don’t sweep Harris County this year, it might take a while. In 2010, statewide campaigns for governor, lieutenant governor and perhaps U.S. Senate may suck up much of the Democratic campaign money in the state, and Barack Obama won’t be at the top of the ballot to bolster turnout. Ike or no Ike, Harris County’s Democrats think this is their year.

For inspiration, Houston Democrats need only look north to Dallas County, where Republicans also dominated local politics, at least until 2006, when Democrats swept every administrative and judicial office in the county. Although the area had been trending Democratic, the GOP was somehow caught off-guard, and the rout stunned Republican strategists statewide. Strategists in both parties realized immediately where the next battleground would be.

The GOP retained control in Harris County two years ago, but the margin was already shrinking. Democrats won 48.5 percent of the countywide vote in 2006, an increase from previous years. “They were competitive, but they all lost,” says Richard Murray, political scientist at the University of Houston.

For Gerry Birnberg, the improved 2006 showing was an important first step. A lawyer by trade, he’s been involved in county politics since the early 1970s. Back then, Houston was so thoroughly Democratic that some political operatives didn’t even want to admit to working for Republicans. The first case Birnberg argued before the U.S. Supreme Court involved printers who feared that if they put their names on Republican political mailers—as state disclosure laws required—their careers would be finished.

Read all of it here.

Source / The Texas Observer