Vice President Dick Cheney’s Incredible and Deadly Lie

By John W. Dean / September 19, 2008

By Deceiving a Congressional Leader, Cheney Sent Us to War on False Pretenses and Violated the Separation of Powers – as Well as the Criminal Law

This week, I agreed to deliver a “Constitution Day” talk on a college campus. My talk was not partisan. Yet the subject matter I selected was prompted by the most incredible – not to mention the most deadly – lie Dick Cheney has yet told, which was reported earlier this week.

Last year, Washington Post reporter Barton Gellman and Jo Baker, now of the New York Times, did an extensive series for the Post on Cheney. Now, Gellman has done some more digging, and published the result in a book he released this week: Angler: The Cheney Vice Presidency. The book reveals a lie told to a high-ranking fellow Republican, and the difference that lie made. In this column, I’ll explain how Cheney defied the separation of powers, and go back to the founding history to show why actions like his matter so profoundly.

Cheney’s Bold Face Lie To Congress

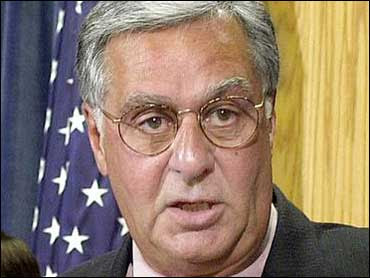

According to Gellman (and to paraphrase from the Post story on his finding), in the run-up to the war in Iraq, the White House was worried about the stance of Republican Majority Leader Richard Armey of Texas, who had deep concerns about going to war with Saddam Hussein. According to the Post, Armey met with Cheney for a highly classified, one-on-on briefing, in Room H-208, Cheney’s luxurious hideaway office on the House side of the Capitol.

During this meeting, the Post reports, Cheney turned Armey around on the war issue. Cheney did so by telling the House Majority Leader that he was giving him information that the Administration could not tell the public — namely (according to Armey), that Iraq had the “‘ability to miniaturize weapons of mass destruction, particularly nuclear,’ which had been ‘substantially refined since the first Gulf War,’ and would soon result in ‘packages that could be moved even by ground personnel.’ In addition, Cheney linked that threat to Saddam’s alleged personal ties to al Qaeda, explaining that ‘we now know they have the ability to develop these weapons in a very portable fashion, and they have a delivery system in their relationship with organizations such as al Qaeda.'”

The Post story continues, “Armey has asked: “Did Dick Cheney … purposely tell me things he knew to be untrue?” His answer: “I seriously feel that may be the case…Had I known or believed then what I believe now, I would have publicly opposed [the war] resolution right to the bitter end, and I believe I might have stopped it from happening.”

In short, it was this lie that sealed the nation’s fate, and sent us to war in Iraq. By lying to such an influential figure in Congress, Cheney not only may have changed the course of history, but also corrupted the separation of powers with their inherent checks and balances.

Cheney’s monumental dishonesty, the news of which has been buried under the current meltdown of the nation’s economy, did not strike me as a topic for a Constitution Day speech. But a realistic discussion of the working of the separations of powers did seem a fitting topic, for college students need to understand the basics of our system. After we remind ourselves of those basics, Cheney’s great lie can be viewed not only as a great immorality and violation of the criminal code, but also and more fundamentally as the significant breach of his oath of office to protect and defend the Constitution that it is.

Our Constitutional Separation of Powers

Historians, not to mention contemporary historical documents, establish that no issue was more important to the founders of our national government than that of what its structure should be. Accordingly, in anticipation of the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia during the summer of 1787, James Madison of Virginia plowed through historical accounts of governments and concluded that there are three basic forms of government: monarchy (the one), oligarchy (an elite few) and democracy (the many). Each form, however, had serious drawbacks.

As a result, Madison sought to take the best of each to create a “republic” – as had been done in varying degrees with many of the American colonies. Republics, of course, had been around a long time, for they were the forms employed by the Greeks and Romans. Thus, the republic was a form of government those who were meeting in Philadelphia well understood, in which sovereignty resides with the people who elect agents to represent them in the political decision-making process.

Madison’s republic combined elements of each type of government, in a mixing of forms. It featured an executive who incorporated the strength of monarchy without the evils of a King; a Senate that embodied the wisdom of an oligarchy; and a House that balanced the self-interest of such elites with a throng of representatives who spoke for the people of the nation.

Many delegates at the founding convention were mistrustful of a pure democracy since none had worked well in the past; moreover, the country was too large and diverse to directly involve everyone. Later, Madison nicely explained the differences in Federalist No. 14: “[I]n a democracy, the people meet and exercise the government in person; in a republic they assemble and administer it by their representatives and agents. A democracy consequently will be confined to a small spot. A republic may be extended over a large region.”

Most importantly, Madison’s structure had three separate branches of the government – legislative, executive and judicial — and each branch was empowered to check and balance the others, and thereby diffuse power.

Madison’s system, however, has not worked as designed even in the best of times, not to mention when there is an all-powerful Vice President hell-bent on gaming the system.

The Reality of Separation of Powers

An article in the June 2006 Harvard Law Journal — Daryl J. Levinson and Richard H. Pildes, “Separation of Parties, Not Powers,” Harvard Law Journal (Jun. 2006) 2311 — provides one of the better analyses out there of the real-world workings of the separation of powers, and their accompanying checks and balances. Professors Levinson and Pildes argue that Madison’s vision of separation of powers has, in fact, been trumped in America by political parties. Their point is well taken, but as I see it their conclusion is far more applicable to the Republicans than the Democrats.

“The success of American democracy overwhelmed the Madisonian conception of separation of powers almost from the outset, preempting the political dynamics that were supposed to provide each branch with a ‘will of its own’ that would propel departmental ‘[a]mbition … to counteract ambition’,” Levinson and Pildes explain. This, in turn, they argue, made the underlying theory of the government – separation of powers – largely “anachronistic.”

When they looked at government, however, they found that when different political parties control the different branches – creating a divided government – then the parties working through those branches still do operate as Madison had hoped. Why? By sifting through the work of noted political scientists, Levinson and Pildes have concluded that it is not on behalf of protecting the institutional powers that the checking and balancing occurs; rather, it is through the influence of party politics operating through that divided branch.

I believe, based on the record (and as someone who worked on the Hill when Democrats controlled both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue) that Levinson and Pildes have it half right.

Democrats under unified government (i.e., when Democrats control both Congress and the White House) have been remarkably institutionally-minded, and the separation of powers has remained viable. On the other hand, conservative Republicans – as I have explained in my book Broken Government (just out in paperback too) – easily place party loyalty before the responsibilities of the governmental institution in which they serve. The first six years of the Bush/Cheney Administration, for example, were a travesty in Republican denial of institutional responsibilities. In contrast, there is a long list of Democratic House and Senate Chairmen who have a on-going history of refusing to be the rubber-stamps of Democratic Presidents.

For instance, unlike in the situation where Cheney lied to former Majority Leader Armey, when both the Democratic House and Senate suspected that President Lyndon Johnson had lied to them about the incident(s) in the Gulf of Tonkin that provoked Congress to authorize the war in Viet Nam, they took action. In contrast, Republicans have not acted on Cheney’s lie to Armey – and surely Washington Post reporter Barton Gellman is not the first person to learn about this lie.

Why Cheney Is Not Likely To Be Held Accountable

Those of us who follow these matters have long known – and I have written before – that it is Dick Cheney who is molding his hapless and naive president to his will, by effecting endless expansions of Presidential powers, and acting upon Cheney’s total disregard of the separation of powers.

Cheney does not seem to believe the Constitution applies to “real leaders,” who do whatever they believe they must do. Nor does he believe in the separation of powers. Indeed, Cheney absurdly claims he is himself part of the Legislative Branch because he is the presiding officer of the Senate – though, in practice, that position exists only to break tie votes. It has long been clear that Cheney has been corruptly bridging the constitutional separation of powers throughout the Bush/Cheney presidency.

If Armey is right, Dick Cheney has not only behaved improperly, but also criminally: In addition, when lying to Armey, Cheney clearly committed a “high crime or misdemeanor” in his blocking the Constitution’s checks and balances from stopping our march into Iraq. During the debates that took place during the Constitution’s ratification conventions, it was specifically stated that lying to Congress about matters of war would be an impeachable offense. Congress has also made it a crime.

Nonetheless, nothing is likely to happen to Cheney, for Congress is too busy dealing with the disastrous economy that he and Bush are leaving behind as they head for the door. No one seems inclined to hold Cheney responsible, and he appears totally unconcerned about the wrath of history. Yet in lying even to those in his own party, about reasons to go to war, he has sunk to a low level few have reached, and it is no hyperbole to call his actions treasonous to the structure and spirit of the Republic.

Copyright © 2008 FindLaw

John W. Dean, a FindLaw columnist, is a former counsel to the president.

Source / FindLaw

Forget impeachment — the statute of limitations on cheney’s crimes won’t run out for a while, I’ll bet — and if things get bad enough the public may feel the need for some blame-placing!