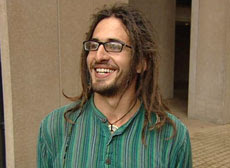

War Resister Robin Long Sentenced to 15 Months in Prison

By Sarah Lazare / August 25, 2008.

Robin Long, an Iraq War resister deported from Canada into U.S. military custody last month, was sentenced today to 15 months of confinement and dishonorable discharge, receiving credit for 40 days of time served.

Long’s supporters, who flooded the Fort Carson, Colorado courtroom where the court martial was held and held a vigil in his honor, expressed dismay at the harsh verdict. “It sets a very chilling precedent that someone who is brought back gets the book thrown at them,” said Ann Wright, a retired U.S. Army Colonel who publicly resigned in opposition to the invasion of Iraq and served as a witness at Long’s trial. “I hope the Canadian government recognizes that.”

Three years ago, Robin Long fled to Canada rather than fight a war in Iraq he deems immoral and illegal. On July 15th, the Canadian government forcibly returned Long to U.S. military custody, making him the first war resister deported from Canadian soil since the Vietnam War.

The Canadian government’s actions flaunt its long-standing tradition of providing safe haven for U.S. war resisters and ignore a non-binding parliamentary resolution to allow U.S. soldiers to stay in Canada.

Long is a part of a growing movement of GI resistance against the Iraq War, and his case has been met with widespread support from friends and allies throughout the United States and Canada

Court Martial

Long’s court martial was held near Colorado Springs, where he was charged with desertion “with intent to remain away permanently.” He was given the maximum time of confinement negotiated in a pre-trial agreement, despite the testimony of several supporters, including Colonel Ann Wright and Matthis Chiroux, an army journalist who recently refused to deploy to Iraq. Long’s sentence stands as one of the longest handed to an Iraq War resister.

Long gave an impassioned testimony at his trial, in which he declared that he was still convinced that he had done the right thing morally, even if he did not make the most prudent legal and tactical decisions. He said that he was glad that he did not go to Iraq but wishes that there was another option available to him other than facing court martial and confinement.

The trial was packed with Long’s supporters, including members from Iraq Veterans Against the War, Veterans for Peace, and the Peace and Justice Coalition of Colorado Springs. The courtroom was so full that many of his supporters had to wait outside. When Long stepped out of the courtroom, he was met with throngs of people who cheered him on loudly, despite being pushed across the street by military police. Long’s supporters have spent months rallying on his behalf, and Courage to Resist raised funds for his civilian lawyer, James Branum.

“I think it was a long sentence but it was positive that he got his day in court and got to speak up and say what he believed,” said Mr. Branum. “His spirits were relatively good. Having two war resisters show up at his trial meant a lot to him.”

Colonel Wright says that she is disappointed in the steep verdict, but she believes the outcome would have been far worse if Long had not received such overwhelming support. “Once soldiers are returned to military control, it is in the best interest of everyone if there is support for war resisters.

Who is Robin Long?

Born in Boise, Idaho, Robin Long was raised in a military family, playing with G.I. Joes and dreaming of one day joining the service. Upon enlisting in the Army in June 2003, the recruiter promised that Long would not be sent to Iraq. Long was excited about this chance to serve his country and finally make something with his life, and he headed off for basic training feeling he had made the right decision. “When the United States first attacked Iraq, I was told by my president that it was because of direct ties to al Qaeda and weapons of mass destruction,” Long told Courage to Resist in an interview in January. “At the time, I believed what was being said.”

Over the next few months, Long’s enthusiasm began to wane. His drill sergeant repeatedly referred to Iraqi people as “ragheads” and led the troops in racist cadences. When Long protested, he was punished by senior officers and alienated by his peers. At this point, Long began to suffer a crisis of conscience. “I was hearing on mainstream media that the U.S. was going to Iraq to get the weapons of mass destruction and to liberate the Iraqi people, yet I’m being taught that I’m going to the desert to, excuse the racial slur, ‘kill ragheads.'”

After basic training, Long was transferred to the nondeployable unit at Fort Knox. Upon meeting soldiers returning from Iraq, Long was horrified by their stories of violence and brutality. Soldiers bragged about their “first kills” and showed pictures of people they shot or ran over with tanks. “I had a really sick feeling to my stomach when I heard about these things that went on,” he said.

In 2005, Long received orders to go to Iraq. The only soldier to be deployed from his unit, Long received a month’s leave to check out of Fort Knox and report to Fort Carson, Colorado. He was scheduled to deploy to Iraq a few weeks later.

While on leave, Long educated himself about the “behind the scenes” story of the Iraq invasion. He talked to friends about whether to go through with his deployment. By his scheduled departure day, Long had made the decision not to go. He skipped his flight and stayed in a friend’s basement in Boise over the next few months. From there he caught a ride to Canada. “I knew that my conscience couldn’t allow me to go over there (to Iraq),” he said.

Long spent the next three years building a life for himself in Canada. He met a woman, had a child and established contact with other war resisters in Canada. Long applied for refugee status on the grounds that he was being asked to participate in an illegal war and would suffer irreparable harm if he returned to the United States. Not only was his bid rejected, but Canadian authorities responded by mandating that Long report his whereabouts every month. He eventually settled in Nelson, a small town in British Columbia.

Orders for Deportation

Robin Long found his new life in Canada to be increasingly precarious.

He was issued a warrant for arrest by the Canadian Border Services Agency on July 4 of this year, on the grounds that he did not adequately report his whereabouts to the authorities, and he was told a few days later that he would be deported to the United States. Long appealed the order, and his supporters rallied throughout the United States and Canada, urging Canadian authorities to let him stay. Despite these efforts, Long was deported on July 15, after the judge ruled that he would not suffer irreparable harm if returned to the United States.

Long’s family remains in Canada, and before the trial, he expressed concern about the separation, which could last a number of years. “I have a son I wouldn’t be able to see. It’s kind of hard to think about that,” he told Courage to Resist.

Canada is home to an estimated 200 U.S. soldiers refusing to serve in the Iraq War, and 64 percent of Canadians favor granting them permanent residence, according to a June 27 Angus Reid Strategies poll. The Canadian House of Commons passed a non-binding resolution June 3rd, calling for a stop to the deportation of U.S. soldiers and allowing them to apply for permanent residency in Canada, but the resolution was ignored by the conservative Harper administration. Several other war resisters living in Canada face the immediate threat of deportation, including Jeremy Hinzman, who received a deportation order for September 23rd.

“We would hope that the Canadian government allow the men and women who refuse to fight a war that Canadians also refuse to fight to stay up there, especially after seeing the heavy punishment that Robin Long faces,” said Ann Wright.

A Growing Movement Against the War

The high profile of Long’s case is also a sign of the growing significance of the GI movement against the Iraq War. As the war effort becomes increasingly unpopular, more and more soldiers are speaking publicly against the invasion and refusing to serve out their contracts, with high-ranking military officials like Ehren Watada publicly denouncing military atrocities, despite facing harsh penalties for doing so.

Meanwhile, Iraq War veterans are teaming up with war resisters and other civilian and veteran supporters to build the GI movement against the war. Iraq Veterans Against the War, whose membership consists of people who have served in the U.S. military since September 11th, 2001, has been active in supporting Long and other war resisters. Several other groups, such as Courage to Resist and the War Resisters Support Campaign (Canada), have risen to support soldiers willing to take a stand. The orders for Long’s deportation were met with protests throughout the United States and Canada.

“Veterans and war resisters are beginning to see that they are in the same boat, that they are brothers and sisters, and it is one struggle,” said Gerry Condon, a Vietnam War resister and active supporter of the GI movement against the Iraq War. “The fact that people are showing this kind of solidarity with each other is really profound. Resistance within the military is certainly growing.”

Source / AlterNet