Officials ‘fearing that the convention will become a magnet for militant protest groups’

By David Johnston and Eric Schmitt / August 5, 2008

WASHINGTON — Federal and local authorities are girding for huge protests, mammoth traffic tie-ups and civil disturbances at the Democratic National Convention in Denver this month, fearing that the convention will become a magnet for militant protest groups.

Officials say that what makes Denver different than past conventions is the historic nature of Senator Barack Obama’s nomination, a megawattage event whose global spotlight could draw tens of thousands of demonstrators, including self-described anarchists who the police fear will infiltrate peaceful protest groups to disrupt the weeklong event.

The Secret Service is wary of discussing threats against the people they protect, but with Mr. Obama poised to become the first black presidential nominee, there are special worries. While law enforcement officials say there are no specific, credible threats against Mr. Obama, they expressed concern about low-level chatter on Web sites frequented by white separatists who spew hate about Mr. Obama’s race and what they perceive as his liberal agenda.

One recent scheduling change caused a major shift in security plans. When Mr. Obama announced last month that he would accept his party’s nomination not at the Pepsi Center in downtown Denver, where the convention is being held, but at Invesco Field, home of the Denver Broncos, the Secret Service scrambled to work out plans with local authorities to secure the open-air stadium, which seats more than 75,000 people. Invesco is also adjacent to Interstate 25, a major corridor through the Northern Rockies that will most likely be closed for at least part of Mr. Obama’s acceptance speech.

“The magnitude of the event has expanded,” said John W. Hickenlooper, the mayor of Denver and a Democrat. “It’s bigger and more profound than we expected.”

Officials acknowledge that their projections for the number of protesters are based more on a worst-case chain of events than specific information about who will show up, but they say they cannot take any chances.

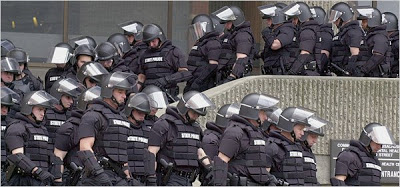

As a result, the Secret Service, the Pentagon, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and scores of police departments are moving thousands of agents, analysts, officers and employees to Denver for the Aug. 25-28 convention. They will operate through a complex hierarchy of command centers, steering committees and protocols to respond to disruptions.

National political conventions are a chance for federal agencies to test their latest and most sophisticated technology, and this year is no different. There was a brief flare-up recently between the F.B.I. and the Secret Service, when each wanted to patrol the skies over the convention with their surveillance aircraft, packed with infrared cameras and other electronics. The issue was resolved in favor of the Secret Service, according to people briefed on the matter.

Both Denver and St. Paul, where the Republican National Convention will be held Sept. 1-4, are enlisting thousands of additional officers to help with security. Even so, their numbers will be only about a third of the 10,000 police officers that New York City fielded for the 2004 Republican convention, just three years after the Sept. 11 attacks.

The Denver Police Department will nearly double in size, according to federal officials involved in the planning. The city is bringing in nearly 1,500 police officers from communities throughout Colorado and beyond, even inviting an eight-person mounted unit from Cheyenne, Wyo. State lawmakers changed Colorado law to allow the out-of-state police officers to serve as peace officers in Denver.

The expressions of concern about security at the convention could have more immediate political and legal implications, too. A federal judge, Marcia S. Krieger of United States District Court in Denver, is expected to issue a decision this week in a lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union seeking to ease security provisions at the convention. The A.C.L.U. has suggested that the Secret Service and the Denver police have exaggerated risks as part of a crackdown on dissent.

The case centers on whether the security zone around the Pepsi Center is so large, and the designated parade route through the city for marches and rallies so far away, as to unnecessarily stifle free speech. New worries about protests and anarchy could bolster the government’s case that the plans are justified.

Last month, under pressure from the A.C.L.U. lawsuit, the city released a list of expenses related to the convention showing that the police were preparing for large demonstrations and mass arrests and that the department had spent $2.1 million on protection equipment for its officers, $1.4 million for barricades and $850,000 for supplies related to the arrest and processing of suspects.

In disclosing the cost breakdown, city officials denied rumors that had circulated for weeks that they had contemplated buying exotic nonlethal weapons that fired an immobilizing goo, or that used radiation or sonic waves to incapacitate people or vehicles.

Similar preparations are under way for the Republican convention in Minnesota, but without the harsh glare that, at the moment, seems to be focused on Denver. St. Paul’s 600-member police force will grow nearly sixfold with about 3,000 additional officers arriving from around Minnesota, as well as from Iowa, Illinois, Wisconsin and the Dakotas, said Tom Walsh, a spokesman for the St. Paul Police Department.

“St. Paul isn’t New York,” he said. “We just don’t have the staffing.”

Kenneth L. Wainstein, the White House adviser on homeland security and counterterrorism, recently visited Denver and St. Paul, a trip that reflected the administration’s interest in the conventions. “In the post-9/11 world, you have to prepare and plan for all contingencies,” Mr. Wainstein said. “That means preparing for everything from a minor disruption and an unruly individual to a broader terrorist event. We need to plan for everything no matter what the threat level is on any particular day.”

Intelligence analysts, however, have not reported a heightened threat from Islamic extremists or domestic threats from antigovernment groups or environmental militants like the kind that operate in many Western states, according to federal officials. “We just aren’t seeing a credible threat,” said James H. Davis, the F.B.I. agent in charge of the Denver office.

Each convention has been designated a National Special Security Event, which makes the Secret Service the lead federal agency responsible for protecting dignitaries and providing overall security. Other agencies will be on standby.

The National Guard in Minnesota and Colorado will each have hundreds of troops on call to their governors to help civilian medical personnel or bomb squads, for instance, if needed. National Guard specialists trained to deal with biological, chemical, nuclear and radiological weapons will also be available.

“There won’t be a visible military presence,” said Maj. Gen. Guy C. Swan III, director of operations for the military’s Northern Command, which is in charge of the military’s response to threats on American soil.

Each city has been awarded $50 million in federal funds for convention costs, a substantial part of which is being spent on security-related equipment and training. And each city has been enlisting the help of neighboring communities to provide more officers to help police the conventions.

The security and safety of convention delegates and visitors has become an increasingly significant issue in Denver and Minneapolis-St. Paul, where local officials were hoping to avoid complaints, heard in 2004 after the Democratic convention in Boston and the Republican convention in New York, that restrictive security arrangements had nearly locked down the convention sites.

From the start, the Democrats’ decision to hold their convention in Denver and the Republicans’ choice of St. Paul stirred concerns about whether local police in each city had enough officers to deal with a wide range of threats, including terrorist attacks or a lone gunman.

The most pressing fears, particularly in Denver, are that as many as 30,000 demonstrators may sweep into the city to disrupt the convention. Much of the city’s planning, in conjunction with federal authorities, has been based on the possibility of such protests, according to federal officials.

Still, these officials acknowledge that they have little concrete intelligence indicating that such large or unruly demonstrations are being planned. But, officials said they had based their assessments on groups like Recreate 68, Tent State and other activist coalitions. Organizers insist the groups are nonviolent, but to the authorities their names alone raise the specter of violent confrontations like those at the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago.

In Denver, federal officials have expressed concern that demonstrators could try to shut down regular business at several major offices, including the Federal Reserve Bank, the United States Mint, and the federal courthouse.

“Because of the Internet, the ability of protesters to mobilize and share information has metastasized,” said Troy A. Eid, the United States attorney for Colorado. “That would be fine if it were peaceful, as we expect. But we have to plan accordingly.”

In recent days, domestic security officials issued a heightened awareness bulletin urging greater attention because of a number of factors, including the election and the conventions. But law enforcement authorities say they are trying to strike a balance between planning for every conceivable threat, including terrorist attacks and large public demonstrations, and not strangling a city’s commercial life in the process.

“We’re not looking to shut down an entire city,” said Malcolm Wiley, a Secret Service agent involved in security planning for the convention in Denver.

Source / New York Times

Thanks to Michael Pugliese / The Rag Blog