Florida Buying Big Sugar Tract for Everglades

By Damien Cave — June 25, 2008

LOXAHATCHEE, Fla. — The dream of a restored Everglades, with water flowing from Lake Okeechobee to Florida Bay, moved a giant step closer to reality on Tuesday when the nation’s largest sugarcane producer agreed to sell all of its assets to the state and go out of business.

Under the proposed deal, Florida will pay $1.75 billion for United States Sugar, which would have six years to continue farming before turning over 187,000 acres north of Everglades National Park, along with two sugar refineries, 200 miles of railroad and other assets.

It would be Florida’s biggest land acquisition ever, and the magnitude and location of the purchase left environmentalists and state officials giddy.

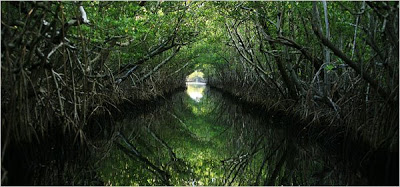

Even before Gov. Charlie Crist arrived to make the announcement against a backdrop of water, grass and birds here, dozens of advocates gathered in small groups, gasping with awe, as if at a wedding for a couple they never thought would fall in love. After years of battling with United States Sugar over water and pollution, many of them said that the prospect of a partnership came as a shock.

“It’s so exciting,” said Margaret McPherson, vice president of the Everglades Foundation. “I’m going to do cartwheels.”

The details of the deal, which is scheduled to be completed over the next few months, and does not require legislative approval, may define how long the honeymoon lasts. Previous acquisitions took longer to integrate than initially expected and because United States Sugar’s fields are not all contiguous, complicated land swaps with other businesses may be required.

The purchase will be paid for with bonds and from fees already added to water bills. But if the price goes up or environmental remediation enters the picture, the state could have to renegotiate or find other money.

The fate of the company’s 1,900 workers also remains in question and some former company executives have suggested that the state is overpaying, bailing out a company burdened with debt, a troubled new sugar mill and a lawsuit from former employees who said they were bilked out of retirement money.

Company officials said the deal would amount to $350 a share, after taxes and other obligations were paid, a premium over two previous offers of $293 per share that the company had dismissed as inadequate.

The accusations and concerns, however, did not dampen the mood. Even as workers from the mill in Clewiston tried to get a handle on their futures, and some cried foul, Mr. Crist emphasized the land’s environmental value.

He said the deal was “as monumental as the creation of the nation’s first national park, Yellowstone.” Declining to provide details of how the state arrived at the price of $1.7 billion, he said it was a terrific bargain.

“I can envision no better gift to the Everglades,” he said, “the people of Florida and the people of America — as well as our planet — than to place in public ownership this missing link that represents the key to true restoration.”

The impact on the Everglades could be substantial. The natural flow of water would be restored, and the expanse of about 292 square miles would add about a million acre-feet of water storage. That amount of water — enough to fill about 500,000 Olympic size swimming pools — could soak the southern Everglades during the dry season, protecting wildlife, preventing fires, and allowing for a redrawing of the $8 billion Everglades restoration plan approved in 2000.

It would essentially remove some of the proposed plumbing. Many of the complicated wells and pumps the plan relied on might never have to be built, water officials said, because the water could move naturally down the gradually sloping land.

Kenneth G. Ammon, deputy executive director of the South Florida Water Management District, which would assume control of the land, said it would be a “managed” flow-way, with reservoirs and other engineered mechanisms to control water flow. David G. Guest, a lawyer for Earthjustice Legal Defense Fund, joked that he might have to go to blows to keep the area all natural.

Read all of it here. / The New York Times

Thanks to Betsy Gaines / The Rag Blog