America’s prison for terrorists often held the wrong men

By Tom Lasseter / June 15, 2008

GARDEZ, Afghanistan — The militants crept up behind Mohammed Akhtiar as he squatted at the spigot to wash his hands before evening prayers at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp.

They shouted “Allahu Akbar” — God is great — as one of them hefted a metal mop squeezer into the air, slammed it into Akhtiar’s head and sent thick streams of blood running down his face.

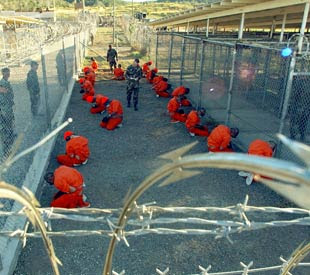

Akhtiar was among the more than 770 terrorism suspects imprisoned at the U.S. naval base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. They are the men the Bush administration described as “the worst of the worst.”

But Akhtiar was no terrorist. American troops had dragged him out of his Afghanistan home in 2003 and held him in Guantanamo for three years in the belief that he was an insurgent involved in rocket attacks on U.S. forces. The Islamic radicals in Guantanamo’s Camp Four who hissed “infidel” and spat at Akhtiar, however, knew something his captors didn’t: The U.S. government had the wrong guy.

“He was not an enemy of the government, he was a friend of the government,” a senior Afghan intelligence officer told McClatchy. Akhtiar was imprisoned at Guantanamo on the basis of false information that local anti-government insurgents fed to U.S. troops, he said.

An eight-month McClatchy investigation in 11 countries on three continents has found that Akhtiar was one of dozens of men — and, according to several officials, perhaps hundreds — whom the U.S. has wrongfully imprisoned in Afghanistan, Cuba and elsewhere on the basis of flimsy or fabricated evidence, old personal scores or bounty payments.

McClatchy interviewed 66 released detainees, more than a dozen local officials — primarily in Afghanistan — and U.S. officials with intimate knowledge of the detention program. The investigation also reviewed thousands of pages of U.S. military tribunal documents and other records.

This unprecedented compilation shows that most of the 66 were low-level Taliban grunts, innocent Afghan villagers or ordinary criminals. At least seven had been working for the U.S.-backed Afghan government and had no ties to militants, according to Afghan local officials. In effect, many of the detainees posed no danger to the United States or its allies.

The investigation also found that despite the uncertainty about whom they were holding, U.S. soldiers beat and abused many prisoners.

Prisoner mistreatment became a regular feature in cellblocks and interrogation rooms at Bagram and Kandahar air bases, the two main way stations in Afghanistan en route to Guantanamo.

While he was held at Afghanistan’s Bagram Air Base, Akhtiar said, “When I had a dispute with the interrogator, when I asked, ‘What is my crime?’ the soldiers who took me back to my cell would throw me down the stairs.”

The McClatchy reporting also documented how U.S. detention policies fueled support for extremist Islamist groups. For some detainees who went home far more militant than when they arrived, Guantanamo became a school for jihad, or Islamic holy war.

Of course, Guantanamo also houses Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged mastermind of the Sept. 11 attacks, who along with four other high-profile detainees faces military commission charges. Cases also have been opened against 15 other detainees for assorted offenses, such as attending al Qaida training camps.

But because the Bush administration set up Guantanamo under special rules that allowed indefinite detention without charges or federal court challenge, it’s impossible to know how many of the 770 men who’ve been held there were terrorists.

A series of White House directives placed “suspected enemy combatants” beyond the reach of U.S. law or the 1949 Geneva Conventions’ protections for prisoners of war. President Bush and Congress then passed legislation that protected those detention rules.

However, the administration’s attempts to keep the detainees beyond the law came crashing down last week.

The Supreme Court ruled Thursday that detainees have the right to contest their cases in federal courts, and that a 2006 act of Congress forbidding them from doing so was unconstitutional. “Some of these petitioners have been in custody for six years with no definitive judicial determination as to the legality of their detention,” the court said in its 5-4 decision, overturning Bush administration policy and two acts of Congress that codified it.

One former administration official said the White House’s initial policy and legal decisions “probably made instances of abuse more likely. … My sense is that decisions taken at the top probably sent a signal that the old rules don’t apply … certainly some people read what was coming out of Washington: The gloves are off, this isn’t a Geneva world anymore.”

Like many others who previously worked in the White House or Defense Department, the official spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the legal and political sensitivities of the issue.

McClatchy’s interviews are the most ever conducted with former Guantanamo detainees by a U.S. news organization. The issue of detainee backgrounds has previously been reported on by other media outlets, but not as comprehensively.

McClatchy also in many cases did more research than either the U.S. military at Guantanamo, which often relied on secondhand accounts, or the detainees’ lawyers, who relied mainly on the detainees’ accounts.

The Pentagon declined to discuss the findings. It issued a statement Friday saying that military policy always has been to treat detainees humanely, to investigate credible complaints of abuse and to hold people accountable. The statement says that an al Qaida manual urges detainees to lie about prison conditions once they’re released. “We typically do not respond to each and every allegation of abuse made by past and present detainees,” the statement said.

LITTLE INTELLIGENCE VALUE

The McClatchy investigation found that top Bush administration officials knew within months of opening the Guantanamo detention center that many of the prisoners there weren’t “the worst of the worst.” From the moment that Guantanamo opened in early 2002, former Secretary of the Army Thomas White said, it was obvious that at least a third of the population didn’t belong there.

Of the 66 detainees whom McClatchy interviewed, the evidence indicates that 34 of them, about 52 percent, had connections with militant groups or activities. At least 23 of those 34, however, were Taliban foot soldiers, conscripts, low-level volunteers or adventure-seekers who knew nothing about global terrorism.

Only seven of the 66 were in positions to have had any ties to al Qaida’s leadership, and it isn’t clear that any of them knew any terrorists of consequence.

If the former detainees whom McClatchy interviewed are any indication — and several former high-ranking U.S. administration and defense officials said in interviews that they are — most of the prisoners at Guantanamo weren’t terrorist masterminds but men who were of no intelligence value in the war on terrorism.

Read all of it here. / McClatchy Washington

The Rag Blog