And now a word about the war…

By Jim Hightower / June 11, 2008

George W keeps telling us that America is at war. But if were at war, he wouldn’t need to tell us, for we’d be fully engaged in the national effort.

In fact, America is not at war. Oh, our troops and their families most certainly are deep in the hell of George W’s war, but 99 percent of us have no personal involvement in it. We are making no sacrifices whatsoever, not even being taxed to pay for it. We’re at beaches, bars and barbeques this summer – not at war.

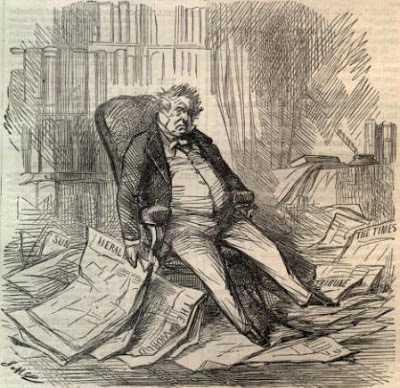

Neither is America’s media establishment. Media monitor David Carr reports that coverage of the war has fallen to a mere three percent of print and broadcast news, down from 25 percent as recently as September. Collectively, network TV is now devoting only four minutes a week to a war that already has killed 4,100 of our soldiers and is draining $12 billion a month out of our national treasury.Why this big media yawn? Some publishers and editors have decided that the “story” isn’t that interesting anymore (of course, if their families were the ones at war, they undoubtedly would find the story riveting). Also, conglomerate owners are cutting newsroom budgets to jack up their profits, so they have fewer reporters to bring us war news.

But perhaps the biggest reason for the drop in coverage is this: the government does not allow it. At White House insistence, the Pentagon has so severely restricted the movements and freedoms of reporters and photographers in Iraq that most can’t do their jobs. Frustrated, many media outlets have simply withdrawn, choosing not to pay for reporters who aren’t allowed to report. I can certainly appreciate their frustration – but, wait a minute, isn’t this government lockdown of our media a rather huge story in itself? Surly that’s worthy of intensive reporting?

Meanwhile, people keep dying in a war that practically no one supports.

Source. / JimHightower.com

The Media Equation

The Wars We Choose to Ignore

By David Carr / May 26, 2008

Gen. John A. Logan was a Union officer, a fierce Republican partisan, an early advocate of the kind of volunteer army the United States now fights wars with. He is also one of the people credited with coming up with the holiday that we celebrate today. A statue in Logan Circle in Washington shows the general on horseback flanked by two female figures said to represent America at war and America at peace.

Given public indifference to a war that refuses to end, perhaps a third statue should be added: America at peace with being at war.

Even as we celebrate generations of American soldiers past, the women and men who are making that sacrifice today in Iraq and Afghanistan receive less attention every day. There’s plenty of blame to go around: battle fatigue at home, failing media resolve and a government intent on controlling information from the battlefield.

According to the Project for Excellence in Journalism’s News Coverage Index, coverage of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan has slipped to 3 percent of all American print and broadcast news as of last week, falling from 25 percent as recently as last September.

“Ironically, the success of the surge and a reduction in violence has led to a reduction in coverage,” said Mark Jurkowitz of the Project for Excellence in Journalism. “There is evidence that people have made up their minds about this war, and other stories — like the economy and the election — have come along and sucked up all the oxygen.”

But the tactical success of the surge should not be misconstrued as making Iraq a safer place for American soldiers. Last year was the bloodiest in the five-year history of the conflict, with more than 900 dead, and last month, 52 perished, making it the bloodiest month of the year so far. So far in May, 18 have died.

Television network news coverage in particular has gone off a cliff. Citing numbers provided by a consultant, Andrew Tyndall, the Associated Press reported that in the months after September when Gen. David H. Petraeus testified before Congress about the surge, collective coverage dropped to four minutes a week from 30 minutes a week at the height of coverage, in September 2007.

It was also pointed out that when Katie Couric, CBS’s embattled anchor, went to Iraq to report the story, she and her network were rewarded with their lowest ratings in over 20 years. Hollywood producers who had hoped there would be a public interest in cinematic perspectives on this war have been similarly punished.

The war remains on the front burner for some outlets. On Sunday, The Los Angeles Times gave over much of its front page to chronicling Californians who have died fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Washington Post continues to personalize the war with a series called Faces of the Fallen.

Earlier this spring, Alissa J. Rubin of The New York Times wrote about flying in a C-130 in Iraq, accompanied by soldiers, including one in a coffin at the back of the plane.

“I wondered what exactly he had died for. And although I did not know him, I felt melancholy as we flew onward, accompanied now by ghosts and memories of loss,” she wrote.

She may have been haunted by her proximity, but the rest of us? Not so much. I asked Bill Keller, the executive editor of The Times, how a war that had cost thousands of lives and over $1 trillion was losing news salience.

“There is a cold and sad calculation that readers/viewers aren’t that interested in the war, whether because they are preoccupied with paying $4 for a gallon of gas and avoiding foreclosure, or because they have Iraq fatigue,” he wrote in an e-mail message, adding that The Times stays on the story as part of an implied contract with its readers.

Other news editors have made the judgment — perhaps prodded by falling revenue and slashed news budgets — that public attitudes toward the war have become so calcified that few are interested in learning more. Why bother when things don’t change?

Except that they do, in a heartbeat. Last Thursday, Steve and Linda Ellis of Baker City, Ore., held a funeral for their daughter, Army Cpl. Jessica Ann Ellis. Corporal Ellis, a 24-year-old combat medic, died May 11 in Baghdad, a victim of a roadside bomb during her second tour of Iraq. She had been injured just three weeks before in a similar attack, but chose to go back out. She was assigned to the Second Brigade Special Troops Battalion, Second Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division and had curly, unruly hair, which brought her the nickname “Napoleon Dynamite” early in her military career.

More than 300 people gathered around this collective wound at St. Francis de Sales Cathedral, according to The Baker City Herald. In the funeral Mass, Bishop Thomas Connolly spoke plainly of her contribution.

“She was a good medic, well-trained and as brave as could be,” the newspaper quoted him as saying.

Hanging in the building where I work, there is a striking picture from the newspaper’s archives (by Angel Franco, a New York Times photographer) of a young soldier in Arizona looking up into the eyes of her father, saying goodbye, her eyes shiny with love and fear. I look at the picture every day as I walk by and think of my 20-year-old twin girls, safe at college. The feeling of gratitude is always followed by guilt. My girls are out of harm’s way, but what about that man’s daughter? What about Ms. Ellis?

On Saturday, her parents received an e-mail message from one of the colleagues in Iraq she was charged with looking after.

“There are wounds that don’t show on the outside,” he wrote. “She gave me the best medicine for what I had — hope and love.”

In a phone call Sunday, Mr. Ellis set aside his grief to describe his loss and the loss to the country she served.

“She wanted to be there for her guys; she told us that,” he said. “She gave the largest sacrifice a person possibly could, selflessly, like she did every day of her life.”

He added, “Jessica was a child who had no care in the world, none, besides making you smile, besides making you feel better.”

And although the Pentagon and the current administration will go to great lengths today to talk about the pride we should all feel in the fighting women and men of this country, increasingly onerous rules of engagement for the news media and the military make it difficult for the few remaining reporters and photographers to do their job: showing soldiers doing theirs.

Yes, the message seems to be, we honor the dead, but do not show them in your pictures. Of course, we care deeply about the wounded, but you now need their signed permission to depict their sacrifice. As the number of reporters and photographers has gone down, the efforts to control those who remain have gone up.

Ashley Gilbertson, a freelance photographer who has covered the war for Newsweek, Time and The New York Times and has written about covering the conflict in a book called “Whiskey Tango Foxtrot,” will be going back to Iraq in June. It will be his sixth time there, temperatures will range up to 130 degrees, and each time he has gone back there have been new restrictions.

“Many of my colleagues have turned away from the story because it has gotten to the point where they feel they just aren’t going to get anything useful, which I completely understand,” he said, adding that nonetheless, when the surge ends this summer, he wants to be there to chronicle what follows.

General Logan wrote long ago that both the glories and the consequences of war needed to be shared by all. He warned against “the dangers of confining military knowledge to a comparatively small number of citizens, constituting the select few who may hold the destinies of the country in their hands.”

Source. / New York Times

The Rag Blog

The government is kicking our asses on so many levels. I am, of course, limited by my age (35) and experience, but it seems to me that things are as dreadfully fucking bleak as ever, and today’s youth can’t be bothered to raise a fuss, so long as they have their myspace, their red bulls and vodka, and ipods. My depression is finally turning into outrage, and I just about can’t fucking stand it